Books

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Cusackian Academy

The other day I started drawing up a list. It started out as a list of people you should know, but then it took on its own life in the realms of my imagination as an assemblage of notables whether of thought, word, or deed. There is, of course, an Académie française, so why not an Académie cusackienne?

Membership of this list does not necessitate approval or sanction. It is more that these are the stars that speckle the Cusackian sky and in some way shine down providing some form or another of illumination. Some I like, others I admire, others still I disapprove of but at least find amusing. (Some, such as that swine-herding relativist Maurice Barrès, I strongly disapprove of.)

As you might expect, it’s rather French-heavy, with a disproportionate dash of Magyars as well. Needless to say, very few of these illustrious academicians are still amongst the living. (more…)

Hark, the Heralds!

by Jack Carlson

133 pages, hardcover, $15.99

In anticipation of a party in Oriel recently, I enjoyed a pint with some friends by the fire in the King’s Arms and was given a copy of this book, mysteriously shrouded in a plastic bag. Jack Carlson’s Humorous Guide to Heraldry is a welcome addition to the Cusackian library. The author, who wrote the book when he was fourteen, is now an Oxford archaeologist (and rower) but his interests span a broad spectrum. (He is currently researching for a work on rowing blazers, a subject unjustly neglected by academics).

Aficionados of the light-hearted-guide-to-heraldry genre will notice one or two gentle riffs off of Sir Iain Moncrieffe of that Ilk’s Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated, and, since that book is long out of print, evangelists of heraldry will find A Humorous Guide to Heraldry a useful tool for introducing the uninitiated to the appreciable realms of this field. Godfathers will not want their spiritual charges to grow into adults without being able to distinguish the mêlée from the affronté and every life-long student of the world should be able to recognise a cinquefoil or a pheon.

In short: a worthy purchase for the heraldically inclined.

Jack Carlson’s A Humorous Guide to Heraldry is available here.

Return to Downside

Christmas was marked by a return to the Abbey Basilica of Saint Gregory the Great at Downside for Midnight Mass. The abbey church always has a splendid feeling at night. One of the best points at the wedding of the century was in the evening when, after a fair bit of dining and drinking, a whole slew of guests slipped into the church where the monks who a few hours previous had sung the nuptial mass were singing compline and joined in their prayers.

Doubtless you will recall last year’s Christmas diary documenting my holiday with Garabanda, Ming, und Familie. In the time since then, my own parents have very wisely moved onto the same landmass as I, and — even better — moved to nary a half-hour’s drive from Downside, so this Christmas was spent in blessed Georgian comfort with my own parents and all the delights of that particular patch of the West Country. (more…)

Gregor von Rezzori

THE BOOKS OF Gregor von Rezzori, according to the introduction to this interview (found via Three Percent), depict “a world now almost wholly disappeared—Central Europe in the years between the two world wars—through the memories, ruminations, and loves of their narrators, men who have survived into the postwar new Europe but who can never fully detach themselves from that lost world. It is Gregor von Rezzori’s world, too. An Austro-Italian nobleman born in the Bukovina region of Rumania in 1914, von Rezzori was raised there and in Vienna. He lived in Germany during and immediately after the Second World War, and he currently divides his time between Tuscany and New York.”

Bruce Wolmer I’m tempted to begin by asking the question interviewers on French TV like to pose: “Gregor von Rezzori, qui êtes-vous?”—Who are you? Which is immediately funny considering that the enigmas and paradoxes—and humor—of identity is a central concern of your work. But one wouldn’t know that reading the reviews, where you’re almost inevitably conflated with the first-person narrator.

Gregor von Rezzori Absolutely. This is such an old discussion: To what extent are books autobiographic? It’s ridiculous. As Flaubert famously said, Mme. Bovary c’est moi. You can’t eliminate yourself totally unless you’re Shakespeare.

BW That goes against the grain of much contemporary opinion and practice, which claims to be getting down to the truth of the author rather than the truth of the fiction.

GvR The Death of My Brother Abel is narrated by a writer. The narrator, the “I”—and funnily enough he is less my own person than any other first person in any of my other books—the narrator in The Death of My Brother Abel is a totally fictitious character. But, of course, nowadays people have little curiosity about examining such complexities. There is this desire of authenticity and transparency which connects with the curious contemporary belief that everybody is, or should be, an artist.

I must tell you that when I was young I never had the faintest idea that I should ever become a writer. I studied mining engineering, of all things. I came to writing by accident at a rather ripe age. I never thought of really having the urge to express myself, but obviously I had it in some way or other. But without ever having heard the phrase, I had to find my identity. That’s one of those dreadful verbal expressions. A phrase like that becomes fashionable and then becomes a slogan and becomes really a program for people’s lives. Every young man or girl nowadays ponders about his or her identity without even realizing what it is. My identity is “I”. It takes a long time to learn that that much celebrated “I” is never lost, but never really found either.

Anyway, in my case I was having a period in my life in which I didn’t have anything else to do—this was before the war—so one day I sat down and wrote a story. Somebody got hold of it and sent it to a publisher. They instantly wanted me to write another one, which I did. Because I thought, my God, this is a very agreeable way of earning money. How wrong I was I found out later. But by then it was too late.

BW A disagreeable way of not earning much money.

GvR Yes, yes. Somebody with a little bit more intelligence doing the same amount of work, you’ll become an Onassis. Well, who needs that? But it’s in real disproportion. Then when I realized what crap I had been writing, you see, I sat down, and just then the war came. I was fortunate—I didn’t actually have to be a soldier exactly. I was born in Bukovina, Rumania. Before Rumania went into the war it was given to the Russians so I was already more or less a Russian although I still had a Rumanian passport and was living in Vienna at that time. When Bohemia was taken by the Russians I went to our ambassador in Berlin, who was a friend of the family, and I said, “What shall I do, what am I supposed to do?” He said, “Well, you are supposed to go home and find a new identity because you don’t exist. And then you’ll die from Mr. Hitler because within a short time you shall have to join in those struggles. I can’t prolong your passport. How long is it still valid?” I said. “For a year.” He said, “Keep quiet.” Which I did. It lasted for three more years during the war. I had my share of bombing and all that, but in the meantime I had the opportunity to really fill the unbelievable gaps in my knowledge by reading. I must tell you that I read very slowly and I need months to finish a real masterpiece, for example one of Broch’s novels.

BW I too read very slowly, and The Death of My Brother Abel took me a couple of months, which was fine, but it was interesting to see in the reviews how impatient everybody is: “Well, yes, there are wonderful bits here, but we shouldn’t be required to sit and…”

GvR Yes, the chutzpah to offer you 600 pages!

BW If one were to race through it, though, to read for information, one would lose a sense of the sheer intensity of the language. There are sentences in The Death of My Brother Abel so beautiful that they quite literally stopped me for five or ten minutes.

GvR What makes for the beauty of Proust, say, is that each page is a picture in itself. But it seems that to get people to read a thick book you need to offer them a juicy subject. Look at Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. People are buying it, people are reading it like mad. For the so-called information, I suppose. A dreadful book.

BW When did you begin to think of yourself seriously as a writer?

GvR In Germany, right after the war, something absolutely absurd happened. You see, I sat down and for the first time I really wrote aggressively and got rid of all my hatred against a particular kind of German. I wrote a book—it wasn’t published until 1954—which the publisher rather ludicrously decided to call Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad —”Oedipus Triumphs at Stalingrad.” But while I was writing that I was also working for the British-controlled radio in Berlin. One day there was a gap in the program and they said, “You are always telling us your silly stories, Jewish jokes, and God knows what all, now go and tell them on the microphone.” Well, there’s nothing more unbearable than somebody who tells one joke after the other. So I combined them into an invented country, which I called Maghrebinia. To make a long story short, the broadcast became a roaring success and the stories from Maghrebinia came out before the novel. With the consequence that, you know how Germans are, from that moment on I was The Maghrebinian. Tell any cafè waiter in Berlin or Frankfurt that you are a friend of mine and you will be superbly served.

BW Tales from Maghrebinia were lighthearted, popular stories?

GvR Of course. It was a success mainly because it was the first book after the war that you could laugh at. And it was hilarious and rude and whatnot, sort of Rabelaisian. It was also the first book after the war in which, with all the collective guilt then being felt in Germany, you could read a Jewish joke. As I say, it became a great success. I never got rid of that, whatever I wrote afterwards. It was read in the wrong key, so to say; people were always expecting me to be satirical and to make jokes.

BW Why wasn’t Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad ever translated into English?

GvR It can’t really be translated, because it’s written in sort of German slang as if Ernst Junger were a drunken Prussian officer telling a story in a bar. It’s about German snobbism, about somebody who comes to Berlin in ‘38 in order to conquer the world, a sort of Berlin Rastignac. It pokes fun in a most atrocious way. The next book I wrote after this was a long novel, which has been translated into English as The Hussar. And then came An Idiot’s Guide Through German Society, which also began as a series on the radio. This offended many people because I had my finger in a burning wound. I claimed that in spite of everything that had happened since 1918 in Germany, the social structure had not altered, you still had an aristocracy with enormous prestige and wealth. And I poked fun at all that. But I’m not at all interested in what happens in Germany any longer. My books don’t sell there and my work is not taken seriously.

BW Abel took a very long time to write, yes?

GvR Indeed. More than 15 years. I disappeared for a while, so to say.

BW During that 15 year period while you were working on Abel you went to Italy?

GvR Yes, I was already in Italy. I am in Italy 35 years now.

BW The Death of My Brother Abel is an extremely ambitious book. There are very few contemporary books that have such a level of ambition—in literary terms, intellectually, historically, and even spiritually.

GvR Lady Annan called her piece about it in The New York Review of Books, “Transcendental Chutzpah.” Well I mean, see, it’s a book for writers. It’s not a book for readers. I like to joke that it should be read in creative writing classes. It is not for the normal reader. It took me 15 years to do and was my own attempt to understand what I was doing as a writer.

BW One of the issues explored in The Death of My Brother Abel is the death of Europe. Europe as a culture, as a way of life. That death has been, at least partially, to the benefit of America. You have that extraordinary, almost hallucinatory, passage in which your character Jacob G. Brodny, born in Central Europe but now a fabulously successful American literary agent and wheeler-dealer, is seen to wolf down the masterworks of European culture as if they were patè.

GvR My aggressiveness is not directed against America and Americans, it’s against Americanism, which is mainly a European phenomenon. Brodny is not genuinely an American. He’s an immigrant who came over here. He behaves more American than any other American, which you can see. And personally, if you ask me, I love and admire America. European culture has not been killed by America. It perhaps committed suicide during the First World War. And this is a thing which I also want very much to emphasize in the next volume of mine, which will be called Cain.

BW The idea of a culture committing suicide is right beneath the surface of Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, as well. Reading it, one becomes aware that the killing of the Jews in Europe, the Holocaust, was not only murder, but the suicide of a world, because for all the antagonism and dislike between the aristocratic and the Jewish characters, they existed in some necessary relationship, some vexed sympathy. They both shared a world that has now vanished. Perhaps it was just that that world vanished, but Jews lost something rich and irreplaceable as well. The moral difference being, of course, that nobody gave the Jews a choice in the matter.

GvR You see, first of all, I do believe that the aristocracy as a class never hated the Jews. On the contrary, the Jews were an object of jokes or disdain, in fact, but many other groups were much more so. As for the peasants and the Jews, it’s a somewhat different story. Whatever a peasant produces is by his hands and due to rot away. He slaughters the pig, but he can’t keep it for any more than a week or so. The Jews, on the contrary, had something that increased its value with time: money. That’s why it was easy for the peasants to believe that the Jews were the evil, exploiting ones.

BW Elie Wiesel has described Abel as an elegy, “the story of Europe seen through the eyes of despair.” How would you describe what has been lost from that world?

GvR Ah ha! Let me answer this exactly. What’s been lost is a particular light, a particular quality of air. And pity—the loss of pity is perhaps our greatest loss.

Now we have a completely different feeling for time, for instance. Time itself has changed. This is due to a blind belief in science. The simple fact is that European life nowadays, just like American life, is determined by money, led by money, as let us say a European would have been led by religion in the 14th century. In every aspect of life, money shows the way. It’s not that this loss happened from one day to the next; as a matter of fact, it’s a loss that started with the French Revolution, at least. Well, all this is rather vague. I shall have to find more metaphors for it.

BW Saying this flies right in the face of the optimistic consensus pervading modernity, the belief that most historical change, most technical and social innovations have been, on balance, for the better. You, or at least the narrators of your books, seem on the contrary to regret them.

GvR You see, I’m profoundly distressed, call it skeptical, and I don’t think I’m alone in becoming aware that we’re in a rotten place. We’re a rotten people; our culture is rotten. Deeply rotten. And to me the proof is that whenever we come in contact with another people, they are destroyed. A friend of mine who’s really one of the last really honest dealers in African art told me that he came to tribes which had never before seen a white man. The simple fact is that they look at him, and that he has a knife or lighter or something—it’s already a deadly encounter. You see, it’s lethal for them already. Similarly, I recently came back from China. The Chinese of my time were pig-tailed and Chinese, but nowadays they are exactly like myself, just a little bit more ethnic. It’s not really to their best interest. What I felt there now was that they have gotten rid of political fantasies and are fortunate enough to have had a religion, an early religion, sort of a black beaten-down art, so they can cope with such a loss in a rational way.

BW In your books there are passing references to the futility of revolution and of politics more generally. Were you affected, as were so many of your generation in Europe, by utopian hopes?

GvR Yes, of course, as a young man. Of course. I couldn’t very well escape from this. In the atmosphere of the ‘30s we all believed, even without an articulate ideology. We all believed in a new world that was about to come. The promised technology. Utopia. Look at the paintings of Kupka at that time. You saw Metropolis everywhere. And Metropolis is not thinkable unless a new man and a new woman are created, a new mankind. In the ‘20s and ‘30s we were unbelievable optimists, you see, who were then bitterly disappointed. But my skepticism, my pessimism, is not just the result of political failure. It goes much deeper. Much deeper. And I haven’t found an answer. I mean whenever I think of it, of what’s been lost, it certainly hasn’t been lost by the Americanization of Europe. What I call Americanization would have happened even without America. The greed for money, the power of technocracy and misunderstood science and so on, all that would have happened even without the example of America. What has been lost is pity and the capacity to dream. You Americans still have the capacity to dream even if you are also sleepwalking in a merry way. But we can’t any longer. We’re awake. Too much awake. Europe is silent and exists now in an abstract way, totally according to abstract rules. For instance, when I say we’ve lost pity, you can see just one small example of it in, say, the demonstrations for the victims of Mr. Pinochet or whoever. But you wouldn’t find those vociferous protesters caring about the beggar on the street. That direct relationship between human beings is getting lost due to abstract ideas about humanity.

BW Ideology.

GvR Yes. Ideology. Political ideology.

BW Which, of course, is a major theme of The Death of My Brother Abel: the increasing abstraction of life, the emptying out of experience.

GvR Exactly.

BW Which leads to the question, Pilate’s question, your books pose so often: What is truth?

GvR What is reality?

BW What is reality and what is fiction and what are the transformations and negotiations between them? You plainly dislike the society of information, the society of media, where people think they’re getting reality from newspapers, television, and magazines. Instead, you’ve said that Anna Karenina — now there’s reality!

GvR Do you remember in Abel there is a long, long, perhaps much too long passage on the narrator’s having an affair with a girl who lives in one of those postwar high-rises. He visits her and thinks about the fictitious reality forced on us by the media and how you lose your identity because you don’t know who you are to cope with all these things which are much beyond your reach, beyond your personal sphere. I mean everything in our time is done, is given, to lose your identity. Then, of course, you have to go look for it, to put it primitively.

BW In terms of your own writing, how does that govern your aesthetic? Not to put too fine a point on it: Why do you write?

GvR Yes, yes, yes. Why do I write? “What sin to me unknown/Dipped in ink, my parents or my own?” Listen, I suppose that in fact writing, whether you know it or not, is the attempt to find an identity. Knowing the secret of the “I” that never can be lost in spite of all the changes it undergoes throughout a lifetime, there you have already the secret theme of every fiction writer, don’t you think so?

BW The search for the voice?

GvR The search for the voice. Also the search for the secret of transformation, of living many lives in one life. The possibility of what I do, of writing hypothetical autobiographies endlessly. And, I mean, Anna Karenina is a reality in so far as it is the most dense invention of fiction, the most concrete.

BW You frequently allude to Nabokov’s saying that when we speak of reality we must put it in question marks.

GvR In quotation marks. Which, of course, are also question marks here.

BW What has been Nabokov’s influence on you?

GvR Well, there were many other influences first. I didn’t read Nabokov until late. But when I had started to write Abel in its first version, I got Nabokov’s Pale Fire in my hand and instantly put my pen down because I found that there was the book I wanted to write already in the best possible form. Then I collaborated on the translation of Lolita into German, and I became aware that I shall never achieve the almost medieval craft of Nabokov’s to link fiction with literary allusion and write a book on many layers—of which one is a direct and fictitiously concrete reality, and behind there is the other reality, the literary reality of all the allusions, all the relations of literature with other literature. At the same time that it’s discouraging, it’s very challenging.

BW Other influences?

GvR Everything influences you as a writer, whatever you read. I believe there isn’t any such thing as a bad book, because you take out of any book something by which you learn, even if you throw it away. Then there are writers who encourage me immensely and writers whom I admire so much that I put down my pen and say, “I can’t write.” For instance, I can’t read ten lines of Robert Musil and keep on writing, I stop for a week at least. Even Joyce. He discourages me totally. But then there are others who encourage me. Thomas Mann with his sort of schoolboyish sense of humor challenges me to get a little subtler. Ironic. And so on.

BW Cèline?

GvR Well, yes. Not consciously, but the violence. In literature, particularly at that period, a certain barbarism is necessary. Also for the sake of honesty. You can’t be suave and God knows what in a time like ours. Also there is in him an urge for iconoclastic action which was also very much an aspect of German Expressionism after the First World War.

BW Your narrator says he seeks to write in “a style of barbaric haul gout.” There is anger and disgust beneath the suavity and jaunty, nonchalant elegance of your prose.

GvR I’ve become aware that I can only write well out of either love or hatred. Direct feeling. I need that. When I love it becomes, because I am sentimental to the core, it becomes too sweetish. It’s like playing on the cello. The best things are wrought in hatred. The more the world around myself gets nostalgic, the more furious I become with nostalgic feelings. I know there’s something I deeply mistrust in that. In fashion, in modes of living, people are trying to revive bits of history, the ‘20s and ‘30s particularly, that they don’t understand. Take the German painter Anselm Kiefer, who’s accused by some Germans of being nostalgic for Nazi times, which is absurd. But if he is, he’s doing the same thing as everybody else does. Without realizing that they are nostalgic for the ‘20s and ‘30s they are nostalgic for what formed fascism.

BW Kiefer’s watercolor Winter Landscape was used for the book jacket of The Death of My Brother Abel.

GvR Yes. Kiefer also denounces in sorrow and in anger. I like him very much.

BW In Abel, you talk about the relation between individual literary style and the zeitgeist, that it is not we who write, but the times which write us, so to speak, which demand a style of us.

GvR Whatever we do is not only led by our individual fullness but by trends in the zeitgeist, by things that are far out of the reach of our control. We don’t know what happens to us. I mean the simple proof is that if you take a German newspaper of, say, 1934 and read an article written by Dr. Goebbels, you wouldn’t believe your eyes. The crap he has said. And—I know, I lived through it—people read it as if it were the Bible. Intelligent people, but totally blinded at the time. Or, another example I use, people from a particular epoch all have a more or less similar handwriting. You can recognize it as 18th century, or whatever, at first sight. It means that something happens to us which we don’t even realize, in ideas as well as in our way of perceiving the world. For example, the break between Romanesque and Gothic art or, in our own time, the sudden break into abstract art, you can’t tell me that it’s a logical evolution. That is rationalizing it as historians always do—backwards.

BW You’re not saying, however, that individual style doesn’t exist?

GvR It certainly exists. There are artists who are not great in the sense of a new creation but just because they represent in the utmost possible form the style of their period. Somebody like Seurat, for instance, is not a great genius in painting, but still such artists represent their period and the spirit of their period in the purest form. But nothing more, nothing personal.

BW Which would make them inferior to an artist who’s able to…

GvR Picasso certainly is not in that line. He’s overwhelmingly personal and individual. Those others aren’t.

BW And in terms of your own work, you would aspire to…

GvR Oh my God! It sounds silly, but I am so astonished that I can write a phrase at all that I wouldn’t know, I don’t reflect that much. I don’t put myself in any rank or school or anything of that kind. I believe that I’m rather personal, but as for representing a particular zeitgeist…I may. I’d be very proud if I did. On the other hand, I have written in Abel many times that the tremendous fear of any writer or artist who believes that he has some idea, something to say, is that they know perfectly well that at the same time, the very same time, hundreds of others have already either said it or are about to say it or there’s another chap who says it much better and liquidates you totally.

BW You have been widely criticized for having your narrator in Abel say that the postwar Nuremberg trials were a sham. As you yourself covered the trials for the Hamburg radio, I assume that you feel similarly.

GvR Let us put that straight. First of all. I do not believe that the Nuremberg trials were a complete sham. They were a failure and therefore a great delusion. This was not due to, say, moral failing or any manipulations behind the scenes, it was due to my great enemy, stupidity, overwhelming collective stupidity. Or the impossibility, even on the part of intelligent people, to cope with things established by stupidity. For instance, you know there has been endless discussion about the legal basis of the trials. And I hope that I have the opportunity to expand this a little bit more explicitly in Cain, the book I’m planning to follow Abel. This has something to do with zeitgeist, if you want to put it that way. I think that all the great moral energy which was necessary to fight the Nazis—when finally victory was achieved there was a moment of total exhaustion. And nobody any longer seriously believed in what had encouraged millions to fight the Nazis and even to die. I mean many wars have been undertaken for a certain or just cause but never more so than in the struggle against fascism and Hitler. The trouble was that also you became aware that it wasn’t stamped out, just pulverized. My feeling is that instead of having one wicked Satanic dictator or a group of wicked people—the Nuremberg defendants, many of them—who demoralized a whole nation, nowadays it’s pulverized and each of us carries within himself a little bit of that venom, instead of 18 millions Nazis, nowadays there are in this world 500 million Nazis, if not more.

BW The trials, then, were false because they suggested that evil could be juridically exorcised and the world put right again?

GvR It’s like that famous statue of the chaps planting the American flag after the Battle of Iwo Jima. The good cause was fought for and won, and now we’re going to make a law that will eliminate the possibility of having the horrors repeated forever. That was too much. Too high.

BW You say that your greatest enemy is stupidity?

GvR Not mine only. You can claim that a man is born good and not wicked, but certainly not that all men are born intelligent. There’s a question also of quantity. Put ten people together and the quota of intelligence is brought down to almost zero. And if you put one hundred thousand together, well, it’s all over then. Plant a great idea, a magnificent invention, or a great example into the mass of mankind and it becomes what Jesus Christ became—the Catholic Church. Endless chains of misinterpretations and misunderstandings—that’s what I call stupidity. A really stupid and dull person can be as amiable as anybody else—charming, but not intelligent. The accumulating and progressive stupidity of mankind is something I fear. And it can’t be fought.

BW And it’s much more pronounced in mass societies.

GvR Of course. The very moment you form a mass out of a certain number of people, it necessarily becomes a body of stupidity.

BW What values enable you to keep on, to continue writing and living with evident grace and vivacity of spirit, in spite of such profound pessimism.

GvR You see it’s the secret of the “I”. In spite of all the strange morphologies and transformations of myself during my lifetime, the “I” is something unchanged, something I can’t explain, not even to myself, and it has its destiny. I believe in that. I may be very capable of suicide, certainly, but I believe that the hour has to come for it. The hour has to come for my dying, anyway. As long as there is life, I shall try to cope with the outer world.

BW And other people?

GvR Certainly. The strange thing is that I despise the mass but I love other people. It’s paradoxical, but I really do. I feel friendly towards everybody I meet. Basically. But in the whole I despise them.

BW One last question. You’ve said, “I’m an aesthetic absolutist and an ethical nihilist.” Can you elaborate?

GvR (laughter) Ah, but what is there to add to that?

A Rioplatense Kingdom?

New book explores the monarchic projects of the River Plate, 1808–1825

A book recently published in Buenos Aires sheds new light on the difficult transition period between the Spanish Empire on the River Plate and the foundation of the Argentine Republic. The launch party for Bernado Lozier Almazán’s Proyectos monárquicos en el Río de la Plata 1808-1825. Los reyes que no fueron (“Monarchic projects in the River Plate 1808–1825: The kings who weren’t”) was held recently in the Quinta ‘Los Ombúes’, home of the municipal library, museum, and archives of San Isidro, the city in the Provincia de Buenos Aires known as Argentina’s ‘Rugby Capital’.

Proyectos monárquicos highlights the forgotten truth that most of the Argentine ‘patriots’ — San Martín, Belgrano, and Alvear among them — were monarchist, not republican. Proposals involving the courts of Spain, Portugal, France, and even England were proffered, and there was even an interesting proposal to marry a European prince to an Incan princess and offer him the throne of the Río de la Plata. (more…)

Turning the Book on its side

Books are a central obsession of mine. I’ve a reasonably large and ever-increasing library of my own and wherever I’ve called home there have been larger collections available to tap into: the Society Library in Manhattan, the Gericke-biblioteek in Stellenbosch, and the mostly excellent public libraries dotted around lower Westchester. When you see the wide range and styles of the book — it’s size, proportion, paper, appearance — it’s depressing to see how monotonous contemporary book publishing is today. I have a thousand different ideas on book publishing and the wide gaps in the market that are completely ignored today, but here’s one inventive idea I didn’t have.

According to Le Figaro, Editions Point Deux (a subsidiary of the La Martinière group, the third-largest publishers in France) has begun offering what it calls « le plus portables des livres » . These little books are printed on their side to be read like a flipbook rather than in the more conventional format. The idea, apparently, comes out of Holland and has proved successful in Spain, but I haven’t come across it at all in the English-speaking world.

The first question is: what’s the point? At 4.75 in. x 3.15 in., they’re a handy size, but is anything actually gained by turning the text on its side? I imagine it’d be helpful for commuters, but I think it’d be difficult to judge the concept without actually having one in hand and using it, so I think I’ll refrain from handing down a verdict just yet. Very boring of me, I know, but I’ll admit I’m intrigued by the idea.

A book review in the Weekly Standard

While my admittedly small work on the Namibian jugendstil was recently published in Catalan, those who are interested in my review of Xander van Eck’s Clandestine Splendor: Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic can read it in the latest edition of the Weekly Standard.

Unfortunately the magazine’s website is mostly behind a paywall, so readers will have to swing by their local newsstand to obtain a copy.

La mort de la Librairie Française

Among the unfortunate recent victims of Manhattan’s extortionately exorbitant rents is the Librairie Française. Last year the venerable New York institution had its rent raised from $360,000 to $1 million per year. The shop was founded in 1928 by Isaac Molho a Sephardic Jew from Salonika, who was invited by David Rockefeller himself to rent a space on the Promenade in Rockefeller Center in 1935. The Maison Française, in which the Librairie was located, flanked the south side of the Promenade, with the British Empire Building flanking the north — the bit of greenery in-between is called ‘Channel Gardens’ accordingly. The sign on the façade said ‘Librairie de France’ but in conversation I have never heard it referred to as anything other than the Librairie Française.

During the Second World War, the shop also operated a publishing house called La Maison Française that printed Gaullist propaganda as well as titles by French writers like Jacques Maritain, André Maurois, Jules Romains, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. It was the post-war period, however, in which the Librairie Française flourished. (more…)

Alexander McCall Smith & the Sisters of Jaipur

The Scottish writer Alexander McCall Smith — noted for the fact that his books are actually a pleasure to read — pens a letter to readers every few months. In the latest letter, he mentions that he recently attended the Jaipur Literary Festival in Rajasthan’s famous “Pink City”:

But the visit to Jaipur was not all literary festival. My wife and I paid a visit to the Mother Theresa Home in the city, which was, as you can imagine, a very moving experience. Over two hundred residents, most of them with nowhere else to go, no possessions, and no money, are looked after by some seven sisters. These sisters are tireless – completely tireless – and give their lives over to the living care of these abandoned people.

At a time when the Catholic Church is coming under severe criticism for its failures (which have been, understandably, very much in the news), we should perhaps remember the extraordinary work of people such as the nuns of this community, who have done so much to bring love into the lives of those who have nothing and who would otherwise die alone and uncared for. I cannot tell you how moved I was by what I saw and by my conversation with the nuns.

An apposite reminder.

If you haven’t yet read Prof. McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street series, I suggest you float down to your nearest bookseller and purchase the first installation (handily titled 44 Scotland Street) today. They are a procession of delightful stories surrounding a number of fictional characters in an Edinburgh townhouse, and if you’re familiar with the capital city, you might just come a cross the occasional non-fictional friend interspersed amongst the creations of McCall Smith’s mind.

A Seraphic Book Launch in Toronto

Torontonians or those in the general vicinity of that metropolis might be interested in attending the upcoming launch of Seraphic‘s new book, Seraphic Singles: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Single Life. Of course, Dorothy is no longer single but instead happily married to a Scottish friend of mine, and you can see her gleefully prancing about the grounds of the Historical House the happy couple now call their home in this 4m29s video clip.

But when & where’s the book launch you say? It’s Thursday, March 25, from 7:00–10:00pm at the Duke of York Pub, 39 Prince Arthur Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, in God’s Own Dominion of Canada. The book is printed by the Canadian publisher Novalis, and is already obtainable from Amazon.com. Copies of the book will also be available for purchase at the book launch.

Seraphic Singles:

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Single Life

by

DOROTHY CUMMINGS

25 March 2010 (Thursday)

7:00pm–10:00pm

The Duke of York Pub

39 Prince Arthur Avenue

Toronto, Ont.

An Evening at the Travellers Club

Photo: © Zygmunt von Sikorski-Mazur

TO CLUBLAND, THEN, for a book launch. Of course the secret about book launches is that they are often enough a convenient excuse to assemble a whole troop of interesting characters together, with the introduction of a newly published volume occupying a secondary (while nonetheless prominent) role. In this, our esteemed hosts Stephen Klimczuk and Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, authors of Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries, exceeded themselves. For me, the evening actually began not in the Travellers but just around the corner in the Carlton Club. Rafe Heydel Mankoo had suggested meeting up there for a drink or two or three before proceeding thencefrom toward the book launch at the Travellers. Pottering over from Victoria, I arrived at the Carlton and was guided towards the members’ bar where I easily found Rafe nursing a drink beside the hearth.

The usual updates were exchanged of various goings-on that had taken place since our last combination in August. Conversation naturally turned to Canada (where Rafe was raised) and shifted to New Zealand just before we greeted the arrival of Guy Stair Sainty. Guy I first met just four years ago while enjoying a pilgrimage to Rome. We happened to stumble upon him in the Piazza San Pietro (as one does with an odd frequency in the Eternal City), and, as it was my birthday, we invited him to join us for some champagne at this little place that overlooks the square. Guy was then in the midst of completing for Burke’s Peerage the massive, two-volume World Orders of Knighthood & Merit, or “WOKM”, which loomed restively on a nearby table as we sipped our drinks in the Morning Room. (more…)

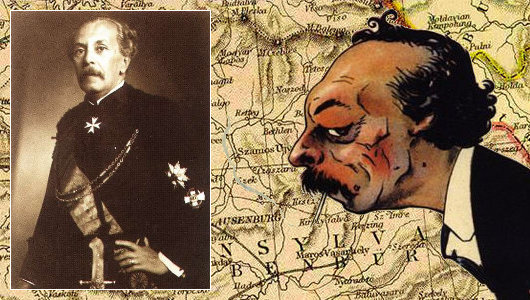

‘The Tolstoy of Transylvania’

In his column in the Daily Telegraph, former editor Charles Moore praises Miklos Banffy as ‘the Tolstoy of Transylvania’. Ardent Banffyites like myself are always pleased when the Hungarian novelist gets attention in the English-speaking world, which happens all too rarely. I can’t remember how on earth I stumbled upon the works of Banffy, probably through reading the Hungarian Quarterly, a publication that — covering art, literature, history, politics, science, and more — is admirably polymathic in our age in which the specialist niche is worshipped.

To put it simply, Banffy is a must-read. If you love Paddy Leigh Fermor’s telling of his youthful walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (the third and final installation of which we still await), then Miklos Banffy will be right up your alley. Start with his Transylvanian trilogy — They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided.

The story follows two cousins, the earnest Balint Abady and the dissolute László Gyeroffy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania, and the varying paths they take in the final years of European civilization. The novels “are full of love for the way of life destroyed by the First World War,” Charles Moore points out, “but without illusion about its deficiencies.”

Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.

After finishing his trilogy, Banffy’s autobiographical The Phoenix Land is worthwhile; some of the real events depicted shadow those in the fictional novels. As previously mentioned, it contains a description of the last Hapsburg coronation (that of Blessed Charles) and numerous amusing tales.

After that, I’m afraid you will have to learn Hungarian, which I have neglected to do, as no more of this author’s oeuvre has yet been translated into English.

The Diogenes Club

“There are many men in London, you know, who, some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows,” says Sherlock Holmes in The Greek Interpreter. “Yet they are not averse to comfortable chairs and the latest periodicals. It is for the convenience of these that the Diogenes Club was started, and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one. Save in the Stranger’s Room, no talking is, under any circumstances, allowed, and three offences, if brought to the notice of the committee, render the talker liable to expulsion. My brother was one of the founders, and I have myself found it a very soothing atmosphere.” (more…)

Beware disgruntled anthroposophists

Readers will be interested to learn that two friends of mine, Mr. Stephen Klimczuk and The Much Honoured The Laird Gerald Warner of Craiggenmaddie, have collaborated on a book that looks to be of great interest. Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries depicts in detail many of the world’s secret nooks and crannies, from mystical sites to enigmatic bolt-holes, debunking myths and positing plausible theories along the way.

After taking an enticing gander at the book’s table of contents, it’s worth popping over to “Curated Secrets”, the blog through which the book’s two authors correspond with one another. The blog already features a picture of the first Goetheanum, the original world center of Rudolf Steiner’s movement that was burnt down by a disgruntled anthroposophist on New Year’s Eve 1922.

Some reading notes

ROBERT O’BRIEN, IN a deliberately provocative gesture, once said in conversation that he pitied America for not having any literature. Preposterous! was my natural response. We have Chaucer and Shakespeare and Mallory and Dickens! Yes, you Britons have them too, but you will have to share, I’m afraid. To try to separate America from the English greats is the equivalent of forbidding a son from taking pride in his family’s long and illustrious history. He may not be the eldest male descendant, but does this mean he must deny his heritage? Of course not. Naturally, like the Scots and the Irish we have our own subset of English literature — Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Flannery O’Connor, and J.D. Salinger come to mind — and there are even a few crossovers such as Henry James and T.S. Eliot.

The idea of doing a degree in English or in any literature has always seemed unattractive to me, though I by no means advocate the abolition of English departments. Perhaps it’s because I rarely found English a compelling subject in high school, though I did have some extremely talented teachers: The P (as she is known), as well as Mr. Leahy. I am one of those no doubt millions who wishes he had actually read all those books he supposedly read for class at school. I did enjoy Sophocles, and Homer too, but I did not really get into Flaubert (I intend to revisit him). Crime and Punishment I soaked up at the time, but have since forgotten.

How tiresome it must be, as a formal student of literature, to be forced to answer questions about works you have read. I wonder if there should be two tracks within universities: one for gentlemen, who merely seek to learn, and another for budding academics, who need proof they’ve learnt something. Some books have taken years (and multiple readings) to truly sink in, so it seems preposterous to arbitrarily require a succinct series of answers to examination questions at the end of a term.

Idea-driven novels seem foolish to me as well. In New York, I knew a Frenchman, not much older than myself, who (I discovered) was in the midst of writing a novel. Intrigued, I asked him one day what the novel is about. He paused for a few moments, sat back, and slowly tapped his finger thrice on the table in thought, and said “Stratification”. Well! Call me a simpleton but I would have preferred “a guy, a girl, a plot, an affair, schoolmates, a day, a week . . .” anything, but “stratification”?

Well, he is writing in French, and if you are going to write an idea-driven novel, it’s probably best to do it in French.

What have I been reading lately? A few months ago I finished Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands — an absolutely cracking book. It was late in the African summer, and I was perched appropriately on the sands of Kogelbaai — one of the most stunning beaches in the Cape. What’s more, it was a weekday afternoon, and so the strand was abandoned but for our small party, so we sat, read, napped, explored the rocks, and enjoyed the beauty of our surrounds. Another cracking read was Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. The author subtitled his book “A Nightmare” and it had moments of utter fear and dread, but also, being Chesterton, moments of ridiculous farce and hilarity: a fascinating insight into the mind and mentality of a jovial and saintly man.

H.V. Morton, the man who convinced me to come to South Africa with his In Search of South Africa, showed me the Eternal City with A Traveller in Rome, and I am so tantalizingly close to finishing that magnificent work of Thomas Pakenham (now Lord Longford, since the death of his father), The Boer War. Pakenham is an historian beyond compare. I began Kristin Lavransdatter to great enjoyment, but am waiting till my return to New York to complete it. I started The Prisoner of Zenda while travelling in Namibia and finished it on Pentecost weekend. Boswell’s Johnson I found an excellent little india-paper edition of in a tiny back-alley shop in Wells last year (we ran into Michael Alexander on the street) and I’ve been pottering through it bit-by-bit. On the recommendation of Stefan Beck I picked up J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man but found it obsessively vulgar and, worse, boring, so returned it to the goodly people at the Universiteit se biblioteek.

I still have out from the library a handsome, handy, small German printing of Legends of the Rhine (translated into English). I like small books, books you can easily fit in the pocket of a field coat and whip out at a moment’s notice. At a reception in a New York gallery some time ago, I learned from John Derbyshire that the determining factor of the old Penguins’ size was that it would fit in the front coat pocket of a British Army officer. The new size of Penguins are much too large to carry about as emergency reading, which makes me very glad that they’ve brought back the older, smaller size.

Penguins aside, I still prefer those shorter, fatter editions printed on thinnest india-paper. Jocelyn, my cook at university, gave me such a copy of The Pickwick Papers (inscribed “To Andrew Cusack — one of the most Pickwickian individuals I have ever met”) for my birthday one year, and it is one of the dearest editions I own. Does anyone print on india-paper anymore? I suspect not, and more’s the pity. Michael Wharton (better known as Peter Simple) noted shortly before his death how difficult it was becoming to obtain sheets of foolscap in London. Thus passes the glories of the world…

Books Cusack Currently Lacks

Food is one of those perpetual worries to those poor souls such as myself for whom the arts of the kitchen are simply incomprehensible. One of the reasons I miss St Andrews was the ready availability of a well-balanced meal at three regular times of the day, even if it was hall food. I sometimes wonder if some earnest benefactor concerned for the well-being of young men recently graduated from old universities might establish a hall-away-from-hall in the major metropolises, in which batchelors can live with decent meals composed of plenty of vegetables and sausages and other such necessities until the uxorial hour strikes.

Anyhow, I stumbled across the existence of the above book, Food, Drink and Celebrations of the Hudson Valley Dutch and am always stumbling across various books of interest, but always either forgetting to purchase them or else pleading poverty (to the ire of the assiduous caretakers of the Cusack library). Amazon, however, allows the user to create a “wish list” of items detailing items one desires which others may purchase and have sent to them; a fine idea. I have assembled a list (currently numbering fifty-two books over three pages) and warmly invite those so inclined to advance the cause of Western Civilization by augmenting the hallowed stacks of my library.

You can view the list by priority, by price low-to-high (irritatingly putting the books available through third parties first), or, for the particularly generous, by price high-to-low.

Some of these (like Paddy Leigh Fermor) are books I have already read but don’t own any copies of, but most of the titles are books I’ve either read reviews of, have flipped through the pages of in bookshops, or which have been recommended by friends. (Some, like Wilhelm Röpke: Swiss Localist, Global Economist, are even by friends). There are also a few advantageously-priced editions from New York Review Books. Have a look, and send along recommendations!

The Primera Revista Latinoamericana

We are of the opinion that the more publications, the merrier, and so we certainly welcome the foundation of the Primera Revista Latinoamerican de Libros. The PRL, which is a sort of Hispanic version of the TLS, started printing last September and is based right here in New York. The bimonthly is published in Spanish but reviews both books that are printed in Spanish and books printed in English. Again, like the TLS, it is not limited to book reviews but features other literary essays as well.

The head honcho at the PRL is Fernando Gubbins, who has earned a master’s degree in Public Affairs from Columbia here in New York and a philosophy degree from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. Mr. Gubbins previously edited the opinion & editorial section of the Peruvian newspaper Expreso, and has worked with the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Not being a hispanophone, I am not qualified to render judgement on the quality of the publication’s content, the PRL in print is well designed and has a very traditional but modern feel to it, and it was a pleasure flicking through its pages. The Primera Revista is a welcome addition to the literary world of New York, and of Latin America.

John Zmirak is “The Church’s Comedian”

Note: This was just sent me by a mutual friend of Herr Zmirak and myself. At first thought it was a wry parody of a ZENIT article but, lo and behold, it is actually a real ZENIT article praising this loyal son of the Empire State (who proudly boasts of his descent from subjects of the Hapsburgs).

Stand-up Apologist

John Zmirak Called to Be Church’s Comedian

by Elizabeth Lev

VATICAN CITY, APRIL 23, 2008 (Zenit.org).- In his 1980 novel “The Name of the Rose,” Umberto Eco dedicated a lengthy erudite section to the question, “Did Jesus Laugh?” Reading the works of Catholic author John Zmirak, he probably laughs a lot.

John Zmirak, a Queens-born author, journalist and apologist, regaled students and adults alike last week in Rome during the launch of his new book “The Grand Inquisitor.”

I spoke to Zmirak about how he reconciled a rapier wit with an ironclad faith, and was fascinated to hear the story of how this prickly pear of piety sprouted in the heart of 1970s Queens.

While other adolescents challenged authority by flaunting curfews or smoking, Zmirak was a youthful rebel for God. During his sophomore year, his religion teachers at his local Catholic high school began teaching notions contrary to the faith. Not being particularly well formed, Zmirak absorbed the doubts and contradictions until one day he was told that the transubstantiation — the change of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ — wasn’t real.

The 15-year-old student balked, remembering vividly his mother explaining that when the bells rang “the bread turns into God.” (This by the way, is a reminder of the centrality of the role of parents in the formation of children.)

Zmirak found a Catechism and read the Church’s teaching for himself. Outraged, the teenager began a letter-writing campaign to his local bishop, persevering in the face of indifference and even hostility. One can almost imagine Zmirak as an early Christian martyr, proclaiming his faith and poking fun at his persecutors even as he faced the lions in the arena.

Zmirak’s unique perspectives and fine mind won him a scholarship at Yale, where he faced the full gale of secular intelligentsia. But he soon realized that it wasn’t the finely reasoned arguments against the tenets of Catholicism that were weakening the faithful, but ridicule.

Zmirak has an unusual take on what undermined the faith of Catholics in America. “It wasn’t eroded by earnest atheists and intellectual attacks,” he states. “What broke down ordinary people was a thousand clever comedic skits.”

So George Carlin and Saturday Night Live’s Father Guido Sarducci are responsible for the rise of the “cafeteria Catholics?” Zmirak says yes. “If you get people laughing, whatever your message is, it slides in unnoticed under the door.”

And thus Zmirak found his vocation. He thought that if humor could be used against the Church, then it could be used for it.

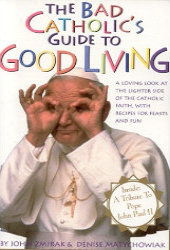

Two of the author’s most popular books are “The Bad Catholic’s Guide to Good Living” and “The Bad Catholic’s Guide to Wine, Whiskey and Song.” Like handbooks for fraternity boys, these books dream up parties, games and drinking activities, all laced with good humor and anchored in Catholic belief.

The good-living guide is dedicated to the fine sense of humor of the Pope John Paul II. Zmirak points out that the Pope not only brought down the Iron Curtain, but also won hearts with his refreshing comedic moments. Even a generation raised on Seinfeld and Monty Python found him accessible.

His guide follows the liturgical calendar with hilarious takes on the individual feasts and recipes and party ideas to celebrate them. In the pages of his book, every day is a reason to make merry in the Catholic world.

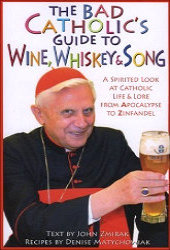

The “Guide to Wine, Whiskey and Song” is the rarest of things — a successful sequel. From A to Z, Zmirak runs through the most well-stocked liquor cabinet imaginable, tracing every form of spirit and elixir back to its Christian origin. In the finest of traditions, he also provides drinking songs, the funniest being Monty Python’s “Philosopher Song” reworked to feature heretics.

Zmirak’s latest effort, “The Grand Inquisitor” is a different genre for him, a graphic novel. Dubbed the anti-“Angels and Demons,” the story is set during a conclave, involves kidnapped cardinals, but champions the cause of orthodoxy and fidelity to the magisterium.

“The Grand Inquisitor” features all the staples of a good noir thriller — dark, graphic design, striking portraits and flashes of razor sharp wit — but contrary to genre which invariably transmits an anti-Christian message, Zmirak’s story is rooted in love for the Church.

After several days with John Zmirak, it became clear that a deep faith and great intelligence provide ballast for what seems to be Christendom’s first stand-up comic. A refreshing reminder of how it takes all kinds to make the Catholic Church.

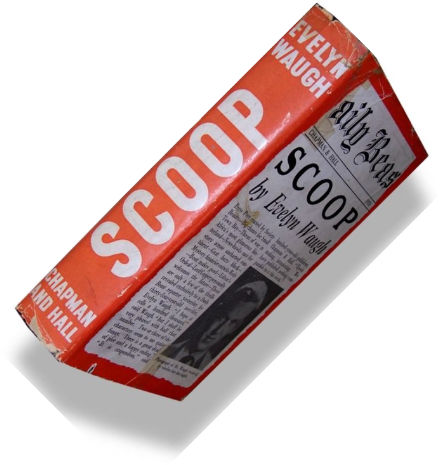

And for the man with $3,500 to spare…

Scoop, by Evelyn Waugh

Chapman & Hall, London, 1938

First edition, hardcover, very good condition.

Small octavo, 308 pages, dust jacket.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Bicycle Rack April 29, 2024

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories