Australia

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The most beautiful city never built

Ernest Gimson’s Canberra

Whenever I’m in in Westminster Cathedral, I feel obliged to nip in to and say a prayer in the chapel dedicated to St Andrew. The apostle is my patron many times over: in addition to being my name-saint, he is the patron of the university, the town, and the country in which I spent four luxurious years. His is one of the most finely decorated chapels in the cathedral, and boasts a beautiful mosaic depiction of the ‘Auld Grey Toun’ above the arms of the donor, the 4th Marquess of Bute. (His father, the eccentric 3rd Marquess, had been Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews.)

Stumbling upon the genial Cathedral Historian, Patrick Rogers, the other day, he shared with me that the stalls and kneelers in St Andrew’s Chapel are widely considered the finest works of arts-and-crafts furniture design in all of Great Britain. They are the creation of a man I had never heard of: the craftsman, designer, and architect Ernest Gimson.

An unfamiliar name is always a potential new avenue of knowledge down which to saunter, and so it proved with Ernest Gimson. His talent at furniture is undoubted but, given my obsession with architecture, it was instead that field of his expertise which particularly drew me in. It was then that I discovered his submission for the 1911-1912 Australian Federal Capital Competition.

The British colonies in Australia federated in 1901, and the dispute between Sydney and Melbourne as to which would be the capital of the youthful nation was settled by agreeing to build a new planned city within New South Wales (the state Sydney is in) but not more than 200 miles from Melbourne.

Ten years later, an international competition was announced to determine the design for this new capital being created ex nihilo on the banks of the Molonglo river, which was given the name of Canberra.

Of the 137 entries received, many of them were very handsome, but some of them were frankly awful. Rather than have a team of architects, artists, or urbanists choose the winning design, the Minister for Home Affairs, Mr King O’Malley, was the sole decision-maker.

He eventually chose the plan submitted by the Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin, awarding a second prize to Eliel Saarinen of Finland, with third prize going to Alfred Agache of Paris.

The design I would have chosen, however, was Ernest Gimson’s.

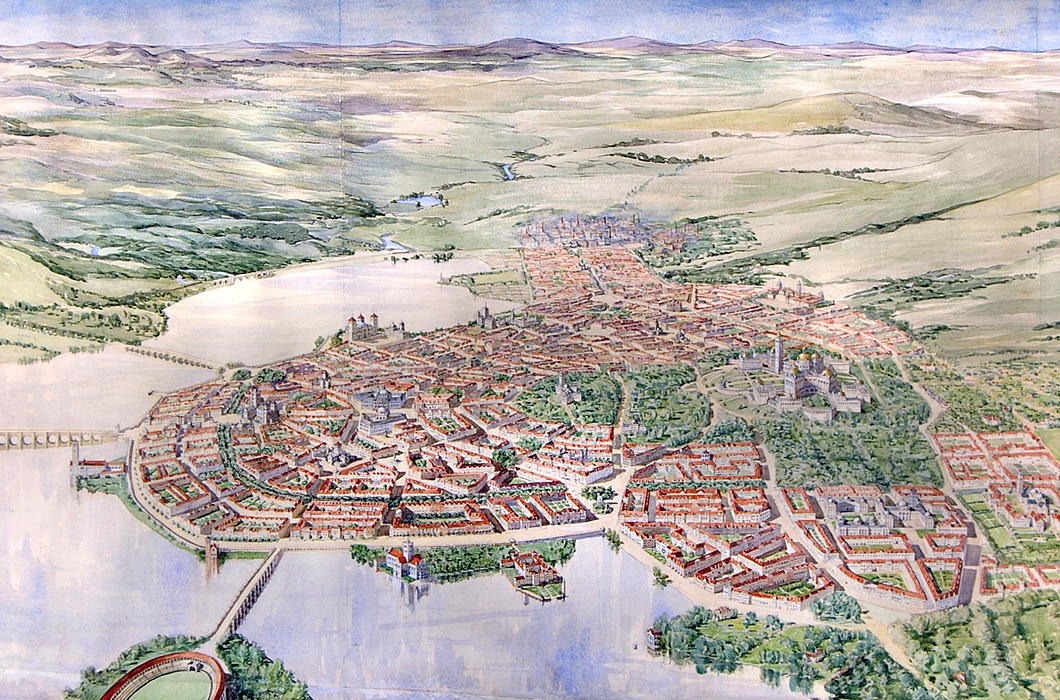

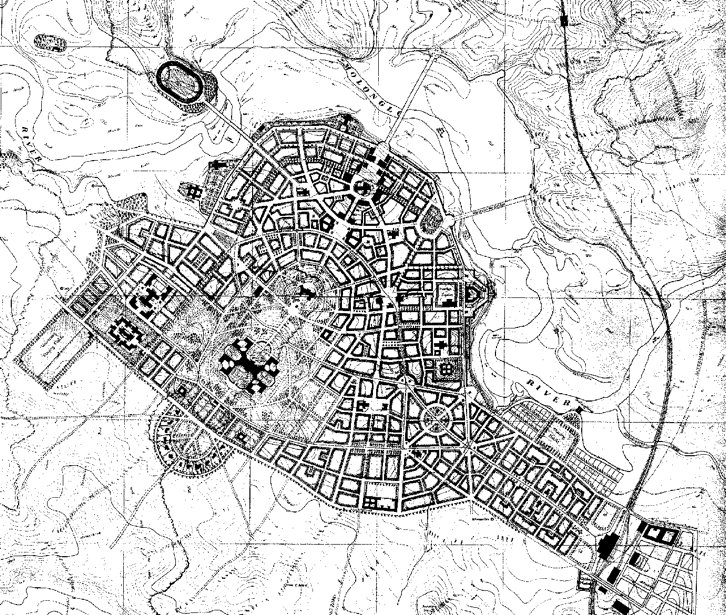

Gimson designed a compact capital city of 25,000 inhabitants that would be able to support itself based on neighbouring farms and small-scale industry.

The city is entirely concentrated along the south bank of an artificial lake and centred on a wooded park containing Kurrajong Hill and Camp Hill, with the streets of the city radiating down from there toward the lakeside.

Kurrajong Hill, with its dominating position over the city, was selected for the Houses of Parliament, with eight departmental buildings surrounding it on a lower terrace.

Official residences for the Governor-General and Prime Minister are located nearby, each with six acres of private grounds.

The State Hall is located atop the adjacent, slightly lower, Camp Hill, with the Printing Office and Mint located at either side, where the park ends.

North-west of Kurrajong is the City Hall, flanked by the Courts of Justice, with its main entrance facing towards the central park.

On a small hill nearby is the University, its double-domed central block surrounded again by ancillary buildings on a lower terrace. Playing fields are allotted nearby.

The market is located on the east side “with a covered arcade for the stalls enclosing an open square”, alongside a market house and technical colleges.

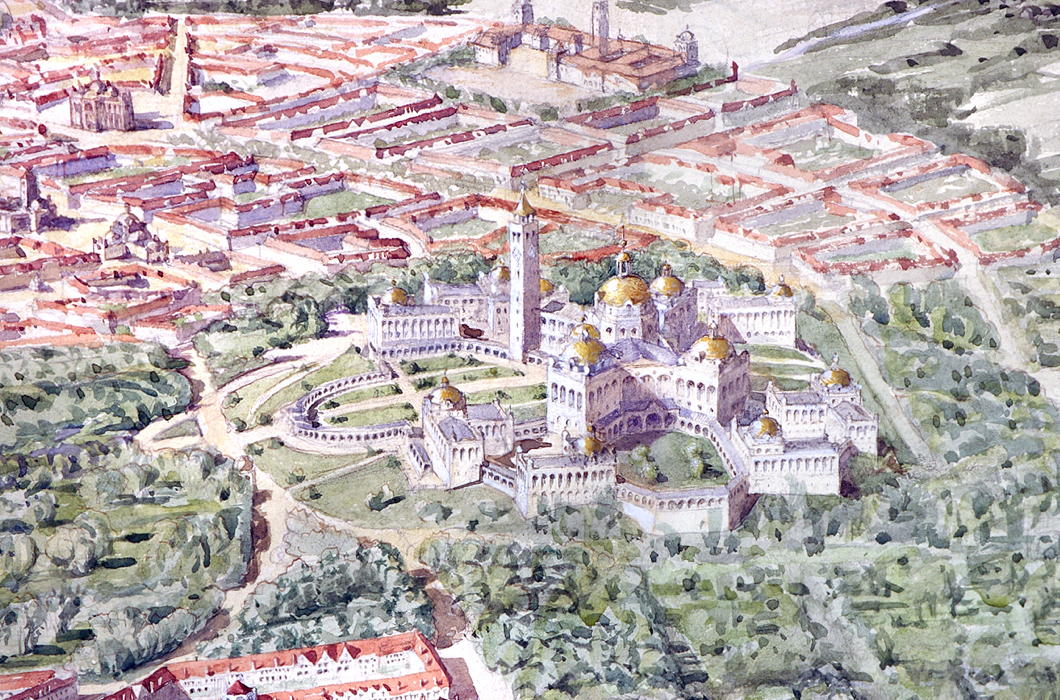

The Cathedral rises from the center of the city proper and forms an axis with the State Hall on Camp Hill and the Houses of Parliament atop Kurrajong.

At the near-midpoint of the street connecting the Cathedral to the State Hall, a public square is flanked by a National Art Gallery and Library. Around the Cathedral itself are the National Theatre and the General Post Office.

A stadium is located on the north side of the lake, connected to the city by a bridge, and further provision is made for siting barracks, gas works, a power station, cattle market, and other necessities.

Buildings would chiefly be faced in a light-coloured local stone which gives the plan, deeply influenced by tradition, both a brightness and a more vernacular feel.

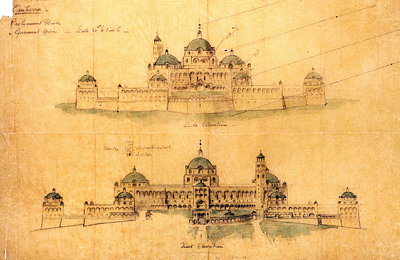

To discuss the design of the buildings is tricky: this proposal is an initial plan and, had it been selected, the architect would have had more time to then further refine what he was proposing.

The Houses of Parliament, with their eccentric X-footprint, are a curious conglomeration and not quite right. There seem to be a surfeit of towers that look too similar to one other.

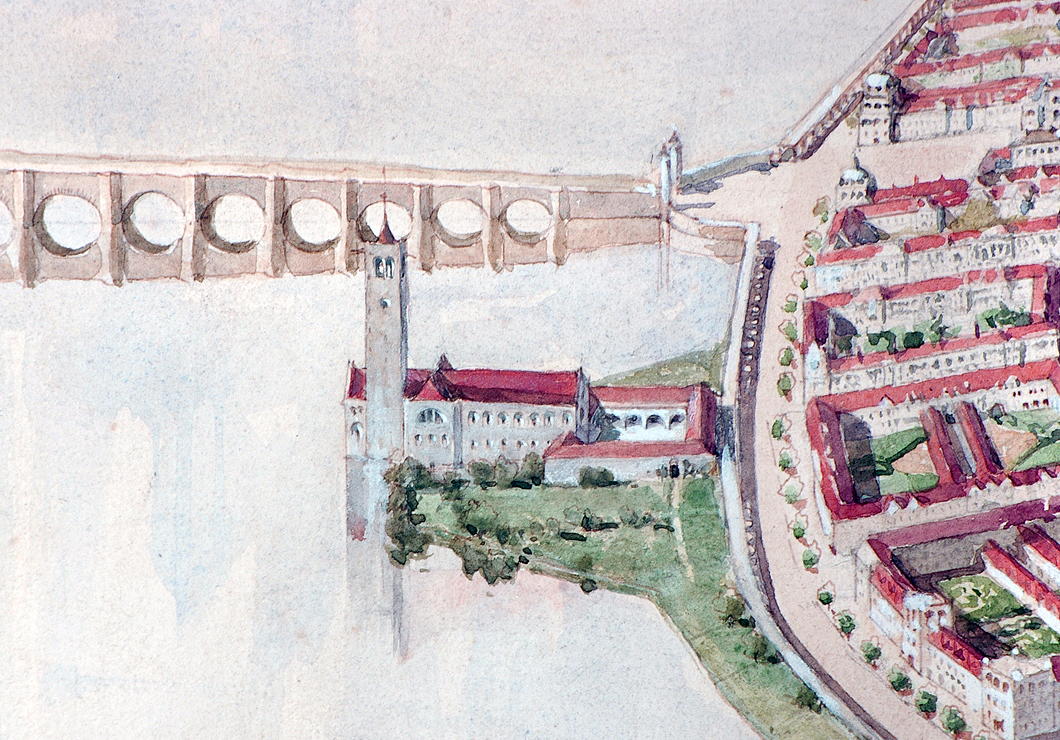

But the Cathedral — my favourite part of Gimson’s plan — is a magnificent creation with an assertive central crossing tower that doubtless would become the visual focus of the city.

The embankment, with its long, generous, 20-foot-deep arcade providing “sheltered walk in hot and wet weather”, is both picturesque and useful.

“While screening in some measure the near part of the lake from the ground floor windows of the houses opposite,” the arcade, Gimson notes, “would enhance rather than diminish, the interest of the wider views.”

Indeed, it provides a useful transition point from lakeside to the rise of the buildings.

The architect’s layout of streets, public spaces, and important buildings, meanwhile, shows the influence of the aesthetic principles of the Austrian urbanist Camillo Sitte, now unjustly neglected since being contemptuously derided by Le Corbusier and other leading modernists.

Gimson’s Canberra is an unpretentious city: its lack of grandeur is what most likely secured its rejection by the fathers of the young and vigorous nation, who were keen to impress. Burley Griffin provided them with a plan redolent of modernity and progress, but marred by fading modishness.

The Gimson plan would have provided Australia a beautiful modern capital city with a design deeply rooted in tradition, and with appropriate consideration of locality and climate. One can imagine that, as the course of history continued, ‘Old Canberra’ would have formed a handsome and much-loved heart of an ever-growing city.

The humane, natural traditionalism of Gimson’s Canberra would have made it much more popular with ordinary people than the sprawling, overly spacious modern city that Canberra is today. Still, it provides a model that urbanists of the future should be mindful of and take inspiration from.

The Advent of Virgin Australia

Virgin Atlantic Airways has always inexplicably attempted a fine balance between the crisply modern and the vaguely old-school. It is also unashamedly British. When the lumbering giants at British Airways were busy banishing the Union Jack from their aircraft livery — prompting Baroness Thatcher to cover the model of a BA 747 with a handkerchief — Sir Richard Branson said “We’re British: why don’t we fly the flag?” The Union Jack was added to every Virgin Atlantic plane and a flag design was later added to the wingtips. Virgin Atlantic now has a patriotic red-head (above) bedecked in the Union flag on the nose of each of its aircraft glamourously advertising their national origins in this hyperglobalist age.

Virgin Group has not restrained itself from expanding beyond the trans-Atlantic flightpath. In 2000, they established Virgin Blue in Australia, originally flying only between Brisbane and Sydney, but gradually expanding within the country, especially after the 2001 collapse of the major domestic carrier Ansett Australia. In 2003, Virgin started Pacific Blue Airways out of New Zealand, operating trans-Tasman routes, followed by the founding of Polynesian Blue in 2005 running flights between New Zealand, Australia, and Samoa. Finally, V Australia was started operations in 2009 running long-haul flights out of Australia. (more…)

Alan Dershowitz Defends Pope Benedict

Benedict XVI has “Done More to Protect Young Children” Than Any Other Pope According to Harvard Law Professor

The Harvard Law School professor & criminal appellant attorney Alan Dershowitz has defended Pope Benedict XVI while speaking to a television news programme in Australia. Dershowitz travelled to the continent to take part in a debate with the lawyer & activist Geoffrey Robinson QC who has waged a campaign to have the Pope tried under international law as culpable for the abuse of children by Catholic priests.

Robinson (a dual citizen of Australia and Great Britain) is well-known in legal and intellectual circles, where he has defended the use of kangaroo courts to try and convict alleged perpetrators of great crimes: his 2005 book The Tyrannicide Brief defended John Cooke, the solicitor general who prosecuted Charles I of England for treason. The Australian academic has also defended the practice of more powerful nations waging war against smaller ones to prevent the latter from committing crimes against humanity, and has argued in favour of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Dershowitz told the Australina Broadcasting Corporarion’s Tony Jones that Robertson’s attempt to have Pope Benedict tried before under international law was “wrong”.

International law deals with war crimes, it deals with systematic efforts by governments to do what happened, for example, in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, in Darfur and Cambodia. This is not in any way related to that. … This is not a crime against humanity, this is a series of crimes by individual priests and others throughout the world and failures by institutions to come to grips with it quickly enough.

Prof. Dershowitz said he thought Benedict has “probably done more to protect young children since becoming Pope than any previous Pope”. (more…)

The Australian

A surprisingly handsome newspaper, especially considering it is owned by (and, indeed, was founded by) Rupert Murdoch. Reminds me of The Scotsman in its broadsheet days.

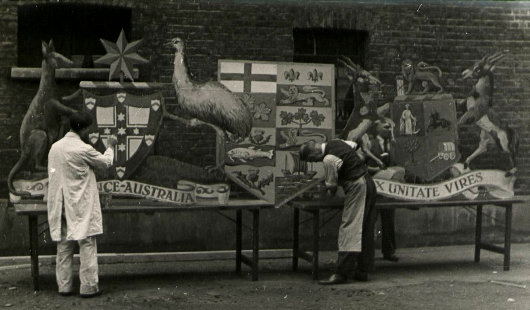

The Evolving Heraldry of the Dominions

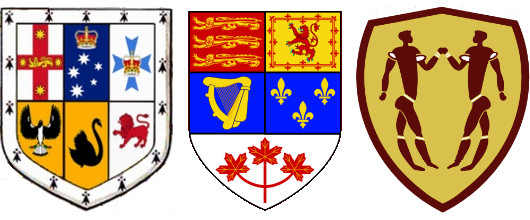

WHAT DO THESE three coats of arms, their representations produced for the 1910 coronation, have in common? The first thing that might come to the mind of most of the heraldically-inclined is that all three are the arms of British dominions; from left to right, of Australia, Canada, and South Africa. Aside from this commonality, however, each of these three arms have been superseded.

The Australian arms above were granted in 1908, and superseded by a new grant in 1912, though the old arms survived on the Australian sixpenny piece as late as 1963. The kangaroo and emu were retained as the shield’s supporters in the new grant of arms which remains in use today.

The Confederation of Canada took place in 1867, but no arms were granted to the dominion so it used a shield with the arms of its four original provinces — Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick — quartered. As the remaining colonies of British North America were admitted to Canada as provinces, their arms were added to the unofficial dominion arms, which became quite cumbersome as the number of provinces grew. A better-designed coat of arms was officially granted in 1921, and modified only slightly a number of times since then.

South Africa‘s heraldic achievement, meanwhile, was divided into quarters, each quarter representing one of the Union’s four provinces: the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State. While South Africa is (like Scotland, England, Ireland, and Canada) one of the few countries to have an official heraldic authority — the Buro vir Heraldiek in Pretoria — the country’s new arms were designed by a graphic designer with little knowledge of the rules & traditions of heraldry. As a result, the design produced is unattractive and very unpopular, unlike the new South African national flag, introduced in 1994, which was designed by the State Herald, Frederick Brownell, which enjoys wide popularity and universal acceptance.

The current arms of Australia, Canada, and South Africa are represented below.

Her Excellency

Quentin Bryce was yesterday sworn in as the Queen of Australia’s representative in her kingdom spanning that southerly continent.

The Pope at Government House

Pope Benedict XVI reviews the guard after being received by Maj. Gen. Jeffery, the Governor-General of Australia.

The Crown of Disenchantment

Over in Great Britain, the House of Commons recently passed the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill which, among other things, keeps the time limit on abortions at twenty-four weeks (in spite a hope that it would be lowered), authorizes the creation of “savior siblings (brothers and sisters deliberately created in a lab solely for their organs to be harvested for use by the already-born), and allows for the creation of animal-human hybrids. The British human rights activist James Mawdsley, famously jailed for over a year by the military junta in Burma, has asked opponents of the HFE Bill to sign a petition to Queen Elizabeth II imploring her to withhold the royal assent necessary for the Bill to become law.

Under the British constitution, a bill only becomes a law when it has received the assent of all three components of the British Parliament: the Commons, the Lords, and the Crown. The last time the Crown withheld consent was in 1708 when Queen Anne refused to sign the Scottish Militia Bill. Since that time, it has been an unspoken convention that should the Crown object to a piece of legislation, it should privately inform its ministers before the legislation is voted upon in order for it to be withdrawn, thus preventing the scandal of the Crown and the Commons appearing to be in disagreement. Despite this convention, however, the Crown still has the right to withhold consent, but merely neglects to exercise that right.

While the Crown has faded to near-irrelevance in the everyday workings of the British government, this was certainly not always the case, and the Crown has intervened in politics several times since Queen Anne’s refusal of assent in 1708. What follows are but a few twentieth-century examples.

In 1925, William Mackenzie King was Prime Minister of Canada with 99 Liberal MPs to the Conservative opposition’s 116. He was able to do this by forming a minority government with the support of the 24 MPs of the Progressive Party. A year later, Liberal MPs were implicated in a bribery scandal and so the Progressives having withdrawn their support for the minority government. As parliament debated a motion to censure the MPs involved, the Prime Minister asked Lord Byng, the Governor-General of Canada (and thus the direct representative of the Crown), to dissolve parliament and call a general election.

Lord Byng did not want it to appear that the Crown was allowing parliament to be dissolved in order to prevent the censure of government MPs and so used the royal prerogative and refused to call an election. The Conservatives, as the largest party in parliament (Lord Byng argued), should have a chance at forming a government instead. The Governor-General invited Arthur Meighen, leader of the Conservatives, to form a government instead, and Meighen agreed. This, in turn, infuriated not only the Liberals but also the Progressives, throwing the middle-man back into the Liberal camp. Meighen put his government up to a vote of confidence, lost it by one vote, and so resigned and asked the Governor-General to dissolve parliament and call an election, which Lord Byng duly did.

“I have to await the verdict of history to prove my having adopted a wrong course,” Lord Byng wrote, “and this I do with an easy conscience that, right or wrong, I have acted in the interests of Canada and implicated no one else in my decision.”

In 1931, when the Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald submitted his resignation to the King, George V took the unprecedented step of asking MacDonald to form a national government with the support of Conservatives and Liberal Members of Parliament. MacDonald lasted as Prime Minister until 1935, but Great Britain would not be governed by a single-party government again until 1945.

More recently, the Crown controversially intervened in Australian politics in 1975. Gough Whitlam’s Labor government commanded a majority in the House of Representatives but the opposition coalition of the Liberals and the National Country Party held sway in the Senate. It is traditional in Westminster-style systems that if a money supply bill fails to pass, the government falls with it. The Senate refused to vote on the annual Budget, in hopes of provoking Whitlam into calling a new election. Whitlam stubbornly refused, and the impasse grew as the weeks passed and, with no budget approved, it looked like the government of Australia would not be able to meet its financial obligations for the year.

Finally, the Governor-General of Australia, Sir John Kerr, used the royal prerogative to dismiss Whitlam as Prime Minister, asked the opposition leader Malcolm Fraser to take the job. Fraser formed a caretaker government solely to pass the appropriations bill then immediately called a new election which his own Liberal/National Country coalition won handily.

Such royal interventions, however, are not limited to the English-speaking world. Belgium’s King Baudouin I, a Charismatic Catholic and friend of Francisco Franco, famously refused to give assent to a bill liberalizing the kingdom’s abortion laws. The Prime Minister, Wilfred Martens, simply had the King declared temporarily unable to reign and the Government signed the Bill in place of the King (as is provided in the Belgian Constitution). Two days later, the Government declared the King able to reign once more, and all was back to normal (except for the unborn children killed thereafter, of course).

One of the great benefits of a monarchy is this: that the Crown act as a source of authority, free from democratic accountability, who is capable of blocking any egregious acts which the government of the day may attempt. The HFE Bill is the perfect example of a bill the Crown ought to reject, for the benefit of all the kingdom, most especially the unborn. Yet we can reasonably assume that Elizabeth II will grant her assent to this travesty of law nonetheless, as the current occupant of the throne has (ironically) so thoroughly and woefully imbibed the democratic spirit that she knows not how to fulfill her purpose and duty as Queen. (It is important to note that in neither the King-Byng affair nor the Whitlam-Kerr affair was the Governor General acting on the orders of the actual person who was the Crown at the time, but rather on their dutiful instinct as the local incarnation thereof). It is disappointing to those who are unflinching in their attempts to defend the British Monarchy that the British Monarchy insists on participating in, and sometimes urging on, the very sort of wickedness which we look to the Crown to protect us from. Alas, so far we have looked in vain.

Who’s still afraid of Keith Windschuttle?

Published in

By Ean Higgins

July 22, 2004

AS the elite of the nation’s academic historians met in the stately rooms of the Newcastle Town Hall, fear and loathing lurked the corridors.

The Australian Historical Association spent virtually an entire day trying to work out strategies to deal with the menace. Would there be safety in numbers if academics stood together? What should be done when the terror struck again? How could anyone survive when the mass media was in on the conspiracy?

Over 18 months after Keith Windschuttle published his book The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, the academic world is still anguishing over its impact. It is terrified of what he will do next. Windschuttle struck at the heart of the accepted view of Australian colonial history in the past 30 years – that the settler society had engaged in a pattern of conquest, dispossession and killing of the indigenous inhabitants. The facts, he said, did not stack up.

The Sydney-based writer, among other things, questioned the references used by academic historian Lyndall Ryan to justify her claims that the British massacred large numbers of Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land in the early 1800s. Her footnotes supporting the claims did not do so, he wrote.

He also took on Henry Reynolds, the venerable historian of the Left, whose depiction of a brutal British conquest of Tasmania had been the accepted norm.

Reynolds’s work on the concept of terra nullius — that the British seized Aboriginal land based on a policy that it was owned by no one — developed such currency that it is believed to have influenced critical High Court judgments on land rights, including the Mabo decision. The thrust of Windschuttle’s thesis was that political correctness had triumphed over historical fact.

With the passage of time, the academic history profession is far from over the history wars. An extraordinary number in its ranks believe they have been been damaged by populist history propounded by Windschuttle. They are searching for a way out. Only a few seem brave enough to speak up, arguing that freedom of expression is the primary issue.

At the recent conference, Ryan made some effort, though ultimately unsuccessful, to avoid media coverage for a talk she gave entitled How the Print Media Marketed Keith Windschuttle’s The Fabrication of Aboriginal History: Implications for Academic Historians.

She said the media had taken up Windschuttle as representing the real history of colonists’ relations with Aborigines, grabbing the view that Australians had been hoodwinked by the academic left-wing historians’ version. “I don’t think the media owns free speech,” Ryan said. She had also been shocked, she said, that Stuart Macintyre, the influential left-leaning University of Melbourne historian, had appeared to criticise her over footnote inaccuracies.

She did admit to five footnote errors, but said the primary sources verified her thesis and “the simple fact is that footnote errors do occur”.

Her abstract said: “The AHA and universities need strategies and protocols in place to address future assaults on academic historians.”

Ryan was not alone in promoting the Windschuttle-media conspiracy. The AHA president, David Carment, said the The Australian had deliberately timed the publication of its review of Windschuttle’s work for the summer of 2002. During holidays more academics were on leave, Carment said, and “less able to defend themselves,” and it was “a time when people were reading newspapers”. (In fact, newspaper circulations fall away over summer holidays.)

It might be time, Carment said, for the association to “defend its people on the basis of their professional integrity” while not taking sides in the debate.

Carment also raised, though he did not fully support, the concept put forward by West Australian historian Cathie Clement for a code of ethics that would gag historians from criticising the integrity of their peers in public. Several in the audience said everyone had to be ready to counter-attack when Windschuttle came out with his next book.

Richard Waterhouse from the University of Sydney, said academics took Windschuttle too seriously. “Sometimes we have tended to treat him as an intellectual equal,” Waterhouse said, adding that sarcasm might be more appropriate. (Windschuttle earned a first-class honours degree in history from the University of Sydney in the 1960s, lectured in the subject, earned a masters in politics and left Macquarie University in 1992 when he set up a publishing house.)

There were a couple of muted mutterings from the audience about how it would be necessary to learn media skills, and not attempt to look like academics defending their own cabal. But nobody at the session publicly asked the key question which was in some of their minds: was the academic historians’ fear of Windschuttle and newspaper opinion pages absolutely paranoid?

Greg Melleuish, from the University of Wollongong, says he is intimidated by the pack mentality of the Newcastle meeting. “I was quite astonished,” he says. “It was like ‘let’s get a group of people together to ambush Windschuttle’. I think they feel under threat and that’s why they concoct these conspiracy theories.”

Other historians have expressed alarm at the attitude of their peers, including classical studies historian Ronald Ridley at the University of Melbourne. “The way they have shut down the debate, if they have made some errors, is really appalling,” he says.

“I don’t think any historians of Greek or Roman history would make these mistakes. And when you deal with issues such as indigenous history, the politics are red hot. You don’t just have to be a competent historian, you have to be top class.”

The question is why academic historians are so concerned about the impact of Windschuttle.

Macintyre, while he does not accept Windschuttle’s suggestion of a fabrication, does warn that mistakes can have a broader effect.

“There is an understandable public concern about the accuracy of historians’ work,” he says. At the same time, Macintyre maintains, Windschuttle fits with a conservative agenda to lift a burden of national shame from Australian shoulders over the Aboriginal issue.

Macintyre told the conference the history wars fitted in with broader “political dimensions” of the Howard Government’s “abandonment of reconciliation, denial of the stolen generations, its retreat from multiculturalism and creation of a refugee crisis”.

“Windschuttle was the first conservative intellectual to base his case on substantial historical research,” he says.

Windschuttle says this is precisely why the academic community is still so scared of him. “There is a whole generation who have invested not just their academic capital but also their political capital in the Henry Reynolds view,” he says. And, says Windschuttle, he has made Australian history interesting again for high school students who are more likely to go on to study it in universities.

While not referring to the Windschuttle debate, NSW Premier Bob Carr, a longstanding history buff, said much the same thing at the conference.

“History is an argument and the more argument there is in it the more young people will read it,” he said.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories