About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

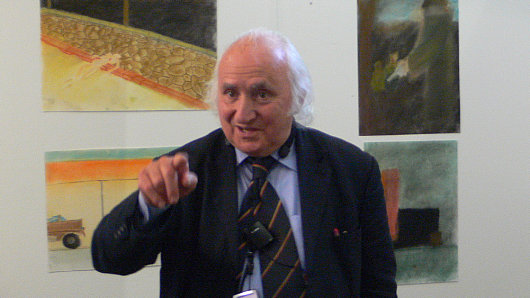

Richard Demarco

“We didn’t know quite how to take this, but we sat there entranced.”

ONE OF THE markedly few deficiencies of the English language is coming up with a word to describe Richard Demarco. The Scottish press have generally settled upon “impresario” but even that somewhat-ambiguous word fails to do the man justice. Ricky was born in Edinburgh in 1930, grew up in Portobello, and remembers the day when his mother held him back from school because Italy — from whence he stock came — had just declared war on Great Britain. He’s attended every Edinburgh Festival since the very first one began in 1947 — as the founders put it, to “provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit” in the grim aftermath of the Second World War.

Richard Demarco, couchant, with noted Scots caricaturist Emilio Coia.

Richard Demarco, couchant, with noted Scots caricaturist Emilio Coia.In 1963, he cofounded the Traverse Theatre, Scotland’s theatre for new writing, and three years after that founded the Richard Demarco Gallery which promoted Scotland’s cultural interchange with artists across Europe including — very importantly to Richard — from behind the Iron Curtain that divided the continent into free and captive halves. This was during an age when many in the arts world were too busy sympathizing with the murderous totalitarianism that had subjugated half of Europe. Richard has been a deep critic of the choices made by the British government as patron of the arts throughout the decades of his life, but not too long ago he finally patched things up with the Scottish Arts Council.

Readers of Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street might recall the man who comes to speak to the Scottish Police College. The “really important person from the art world in Edinburgh”, as Mr. McCall Smith puts it, comes and tells the trainee constables about the gorgeousness of Italian carabinieri uniforms and how the Scottish psyche still suffers from the iconoclasm of the Reformation, and even suggests architectural alterations and more sympathetic decoration of the Police College. “We didn’t know quite how to take this, but we sat there entranced,” the character admits in 44 Scotland Street. Anyone who either knows Ricky or has been to one of his lectures would immediately recognize the unnamed subject of the passage.

I first met the man when I was a first-year student at St Andrews and he had come up from the capital to give a lecture. I can’t remember what the stated subject was but this is entirely irrelevant as so vast and wide-ranging is the mind & experience of Richard Demarco that he is known for (some would say “notorious for”) never keeping within the bounds of the stated subject. Those who invite Richard to speak shouldn’t bother with a subject, just make posters stating “RICHARD DEMARCO SPEAKS”, giving the date, time, and place, and a crowd of interested characters is bound to turn up.

Whenever I’m in Edinburgh — and I try to be in Edinburgh as often as I can — I can’t help but call up Ricky and see what on earth he’s up to, as he’s always up to something. As it happened I was in the capital at the height of festival season, something I had not experienced before. “You must come to my master class,” he said on the phone. “It’s at the Edinburgh College of Art. In fact I’m supposed to be there now.” By the time I had caught the right Lothian Bus (“Exact change only!” Grrr…) and toddled up the magnificent staircase of the Edinburgh College of Art, Richard was not only in full sail but the hour-long class was nearly finished for the day. We got a chance to chat for just a bit but then I already had to run to another appointment — for time is precious in Edinburgh, and old comrades to meet are many. I arranged to come to the next day’s master class, and experience first hand the fruits of Richard’s most recent labours.

The next day’s master class found a clan of Gordonstoun students reading out a play written by a Downside boy. A bit of background is probably required. Richard, who is continually searching for ways to inculcate in the youth of Europe an appreciation for the best of our fading civilization, had taken a number of Downside students to Poland, a country to which he has a particular attachment (and which has awarded him its Order of Merit), to explore the deep history of this profoundly Catholic land which also has numerous links to the school at Downside Abbey. I’ve a fondness for Downside myself, having visited and stayed there a number of times, and at the reception following the wedding of two of my best friends I sipped champagne with a friend beside the beautiful leaded- and stained-glass window memorializing two brothers of Poland’s Zamoyski family — old boys of Downside — who died fighting “Pro Polonia et Anglia” as the window puts it.

The play was set in occupied Poland in the midst of the Second World War, the subject an accomplished but somewhat jaded academic who receives two visitors into his home. The playwright goes by the name of Roland Reynolds, not yet 18 years of age, and a student at Downside. His name is one to watch. Not that the play was the best ever written, but if the lad Reynolds can write a play of this quality while still at school, with the proper self-discipline and development I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if we see his future work in London or New York some day. And yet, the theatre isn’t even his preferred art — Roland is an aspiring poet.

“You must tell us,” Richard asks, “why you wrote this magnificent play, Roland.” “Because you told me to, Richard!” is Roland’s frank response, but he fleshed out the background to the play’s genesis through his journey to Poland with his fellow students and with Richard as guide and mentor.

Roland Reynolds’s play — tantalizingly read only in part during the day’s master class — wasn’t the only artistic creation to come forth from the Demarco-Downside expedition to Poland. I was lucky a friend coming over from Glasgow for lunch was running late, as Richard said I couldn’t leave the Edinburgh College of Art that day without seeing the exhibition still in preparation. Down the grand staircase of the ECA (of which Richard is an Honourary Fellow) and through one of the main corridors to the end and beyond.

“Art schools teach absolute rubbish today,” he said along the way. “Do you remember how it used to smell?” he asked an alumnus of the College walking beside him. “Do you remember how it used to smell of formaldehyde and paint? They don’t teach them how to paint properly anymore. They don’t even teach them how to draw.” His head shook to and fro in solemn disapproval. “It’s disgusting.”

Tucked in one corner of the College of Art was the exhibition. The majority of works were by three Downside students, but there were also photographs from Scottish photographer and filmmaker Joseph Margiotti as well as work by Terry Ann Newman, who aside from her art is also Richard’s indispensable deputy director at the Demarco European Arts Foundation.

Richard explained the significance of Poland’s place in Europe and the world. Freedom, partition, subjugation, rebirth, freedom, occupation, holocaust, subjugation, resistance, and finally — 1989, twenty years ago now — the return of freedom. Like all the newly freed nations of Eastern Europe, Poland has now to deal with the challenges of modernity that threaten to implode the entire continent from within. Politically veering between the scylla of Moscow and the charybdis of Washington, Poland must now attempt to steer her society away from the traps of materialism. To have defeated socialist materialism only to be subdued by capitalist materialism would be a victory as hollow as Poland’s “liberation” at the hands of the Soviets. Having such a rich and profound experience of Catholicism, which has doubtless aided the country’s survival while it was officially wiped off the map, can be nothing but a benefit for this ancient country that stands as a testament to the redemptive power of suffering.

Of course much of the work on view reflected Poland’s suffering, particularly the horrors of the Holocaust at the hands of the Nazis and of the Soviet attempt to decapitate the nation at Katyn. These obvious horrors are positioned in the mind against the more subtle tribulations affecting Europe today. A demographic implosion from the refusal to reproduce. The lives of the old & infirm or the unborn & unwanted carelessly tossed aside. Schools of art that don’t teach how to paint or draw. A generation that refuses to pass on its inheritance to the next. “It’s disgusting”.

But the photographs of Warsaw also pointed to the Third Day — to resurrection and rebirth. “This city was utterly, utterly destroyed during the war. You see this building?” he says gesturing to baroque structure in a photograph on the wall. “Just a pile of rubble in 1945. A heap of stone and bricks. But the Poles took those stones and put them back together. They rebuilt them just as they were before. Well not just as before — we all know you can never rebuild exactly as before — but they did their best. And you can see those stones today. It was destroyed. It was reborn. It survives.”

The challenge of a man approaching his eightieth year to the next generation.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Bicycle Rack April 29, 2024

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories