About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Other Modern in Jewish Amsterdam

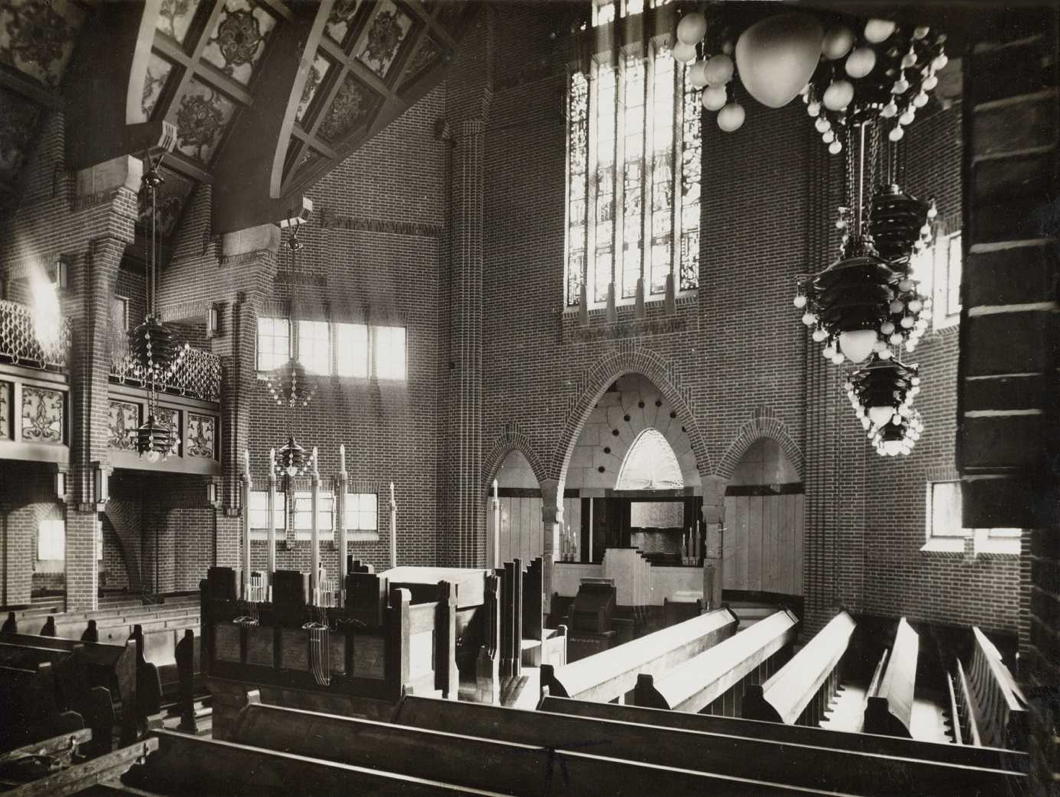

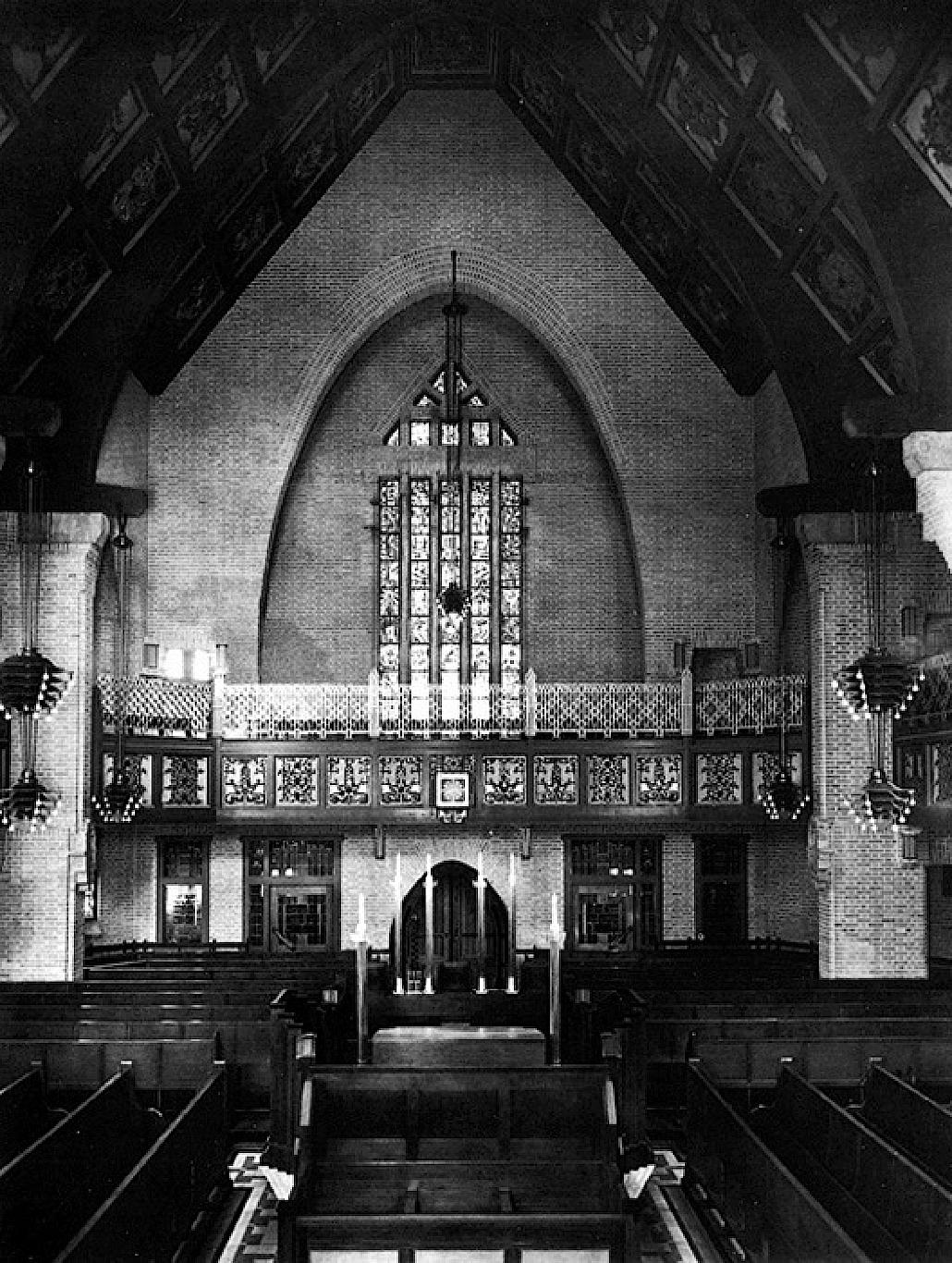

Jacobus Baars’ Synagoge Oost, Linnaeus Street

There were few places where architecture’s competing forms of modernism overlapped more than the Netherlands in the 1920s. Traditionalists like Kropholler, De Stijl’s Oud, Rationalists like van der Vlugt and Duiker, and the versatile Dudok built alongside the work of the capital’s eponymous ‘Amsterdam school’ style.

The influence of the great Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers — Holland’s Pugin — might be inferred as the progenitors of the Amsterdam school (De Klerk, van der Mey, and Kramer) all studied or worked in the firm of Cuypers’ nephew Eduard.

The Dutch capital’s take on the brick expressionism originated among its Hanseatic neighbours but was sufficiently distinct to merit its own name. Architect Jacobus Baars (1886-1956) deployed the style to great effect in the work he did for Amsterdam’s then-flourishing Jewish community.

Baars designed the 1928 Synagoge Oost (East Synagogue) on Linnaeusstraat (Linnaeus Street) in the Transvaalbuurt neighbourhood that was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Dutch sympathies in the then-still-recent Anglo-Boer War are obvious from the naming of local streets and squares (and, indeed, the district) after Afrikaner places, battles, and statesmen.

The architect placed the building at an angle so that the entrance could face on to Linnaeusstraat while the holy ark containing the Torah scrolls faced Jerusalem, skilfully filling in the rest of the site with clergy and school structures ancillary to the sanctuary and congregation.

Appropriate for a city whose nickname “Mokum” comes from the Hebrew word for “place”, this was the most Amsterdammer of Amsterdam synagogues designed in the architectural style the city gave its name to in that decade.

While thoroughly Dutch, Oost was also obviously Jewish: aside from its very purpose, one of the turrets hanging off the façade proclaimed the words of Psalm 121 in Hebrew characters — “We shall go into the house of the Lord” — reminding the Jewish passers-by of the district of their Sabbath duty.

“The atmosphere that prevailed was intimate and tender,” local Salomon Waas remembered decades later in 1978, “and there was no shul in Amsterdam that could match that.”

Needless to say, the congregation could not escape unharmed from the tragic and destructive course of the twentieth century — especially the German invasion and occupation of the Netherlands.

On 20 June 1943, the National-Socialist occupiers raided the Linnaeus Street synagogue, looting the building and rounding up many of its members who lived nearby. Rabbi Meijer De Hond would survive barely a month more before his death in Sobibor camp on 23 July 1943.

After the war, the Sjoel Oost was a ruin, though services continued in part of the building. The numerically diminished Jewish community decided against restoration and the building continued to fall into disrepair until the decision was made to demolish it in 1962.

Nonetheless, some bits of the building survive.

Simon Nordheim, a Dutch emigrant to Israel, was shocked by the state of the building when he visited in 1957. Nordheim worked with the local Jewish authorities to secure the surviving stained-glass windows designed by Leo Pinkof and convinced them to let him bring them to Israel and re-install them in his home congregation in Ramat Yitzhak.

Another local resident, Jan Bodzinga, was playing in the ruins during the war when he found a mezuzah. This ended up with Mordechai Bellegraf, who made his bar mitvah at Oost and it still hangs on the doorframe of his apartment in Israel today.

The building on the site today is housing designed by Bauhaus architect Mart Stam, who took his inspiration from the Soviet-dominated Eastern bloc for this 1966 construction.

As in so many other places, here the more humane “other” modern was neglected and eventually suppressed in favour of the ‘International Style’ of Bauhaus.

In Amsterdam, however, there are signs of hope: more recent projects like Damrak 70 show that some of the city’s wounds are being healed.

Slow and steady wins the race.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories