About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Other Modern

An Architecture of Continuity:

Luis Moya Blanco’s Universidad Laboral de Gijón

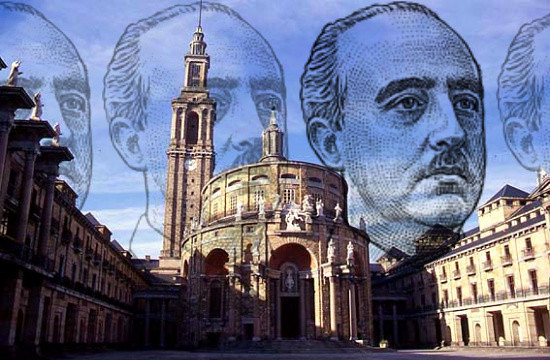

In 1944, an undersecretary of Francoist Spain’s Ministry of Labour visited the city of Gijón to attend the funerals of a group of miners killed in a mine collapse. After the solemn rites took place, Turiño Carlos Pinilla met with a group of locals filled with concern for the offspring of the dead workers. All they asked of the bureaucrat was an orphanage; what they ended up with ten years later was a magnificent palace of charity, almost a city unto itself and the largest building in Spain: the Universidad Laboral de Gijón.

An example of Catholic social teaching (which upholds the essential dignity of work and the working man), the “labor university” was founded as a secondary-level institution to teach vocational and technical skills to the children of Spain’s working class. At over 2,900,000 sq. ft. of space, it is more than double the size of the great Royal Monastery and Palace of El Escorial built by Phillip II in the sixteenth century, and was accompanied by over 380 acres of farmland.

The goal was to accommodate 1,000 students (eventually doubling) from the age of 12 to 16, with residences, school facilities, industrial workshops, working farmland, athletic facilities, and sporting fields. The educational aspect and leadership of the Laboral was entrusted to the Jesuits, while the Poor Clares also had a convent on the premises, performing various household tasks and caring for the girls as their particular charism.

Construction began in 1946, while much of the rest of Europe was recovering from the horrors of the Second World War.  Francisco Franco, meanwhile, had vowed at the end of Spain’s tragic Civil War (1936-1939) to never again take up his sword unless Spain herself was attacked, and the country was spared the further horrors of the global conflict.

Francisco Franco, meanwhile, had vowed at the end of Spain’s tragic Civil War (1936-1939) to never again take up his sword unless Spain herself was attacked, and the country was spared the further horrors of the global conflict.

The Universidad Laboral de Gijón was the first of the handful of “labor universities” founded during Franco’s rule, and some of the brightest minds in Spain were involved in its creation. The gardens, created to train students in landscaping, were designed by Javier de Winthuyssen, the National Inspector of Parks and Artistic Gardens while the farms where students would learn the skills of agriculture were orchestrated by Gabino Figar, Spain’s leading agronomist. The building itself featured sculpture by Manuel Alvarez Laviada and Florentino Trapero, mosaics by Santiago Padrós, and murals by the painter Joaquin Valverde.

The architect, however was Luis Moya Blanco. Born in Madrid in 1904, Moya came from an architectural family. His father (and namesake), Luis Moya Idígoras, was the most prominent road engineer in Spain while his uncle was the head of the School of Architecture in Madrid. Before the Universidad Laboral, Moya was best known for his work on the Museo de America, the museum exhibiting Spain’s artistic and archaeological treasures from the New World, situated on the Avenue of the Catholic Monarchs in Madrid.

Part of the plan of the Universidad Laboral was to act as a miniature ideal city, and the building asserts its independence by facing away from the city of Gijón. Passing through the massive entrance gate, the visitor first encounters the Corinthian Court, a massive atrium lined with ten Corinthian columns 34 ft. tall. Originally open to the heavens, the top of the courtyard was recently given a glass roof.

Through the Corinthian Court, one proceeds into the great central courtyard of the Laboral and is immediately drawn to the church at the center, with the 385-ft. tower behind it, and flanked by the theatre (on the right) and the entrance to the school wing (on the left).

Reflecting the concept of the ideal city, the Church is at the very center and heart of the Laboral. The church is elliptical in shape, but retains the traditional linear liturgical arrangement inside, like all the churches designed by Moya. In the main portal of the Church, above the lintel over the entrance, is a statue of Our Lady of Covadonga, patroness of the Asturias.

The main portal is itself flanked by four columns, two on either side, which are topped by statues of saints: St. Joseph, St. Ignatius, St. Peter, and St. Paul. Atop the portal is St. James the Apostle on horseback, with two angels worshipping a Cross. Originally, this was a specially crafted version of the Cruz de la Victoria, a particular symbol of the Asturias which appears on the principality’s flag, but this precious work of art has since been removed and replaced with a more simple metal version. Circling the church are statues of St. John of the Cross, St. John Bosco, St. Vincent Ferrer, St. Melchor de Quiros, St. Clare, St. Peter of Alcantara, St. Laurence, St. Isidore of Seville, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Dominic Guzman, St. Francis, St. Joseph Calasanctius, St. Eulalia, King St. Ferdinand III of Castile, St. Isidore the Laborer, and St. Toribio de Liébana.

The interior of the church features inlaid marble floors and specially-constructed pews (one of the necessary drawbacks of elliptical churches) made of embero wood imported from Spanish (now Equatorial) Guinea.

The original high altar was removed during the 1970s, but strangely it seems the baldacchino was never completed.

A thin altar rail divided the sanctuary from the nave.

The workshops where students were taught industrial skills.

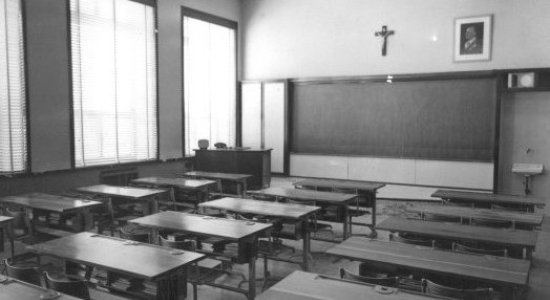

Classrooms all had a crucifix and a picture of Spain’s caudillo.

Franco was present at the official opening of the Universidad Laboral in 1955.

Major construction finished a year later, though one portion of the complex (above left) remains unfinished.

The theatre of the Laboral was the first air-conditioned theatre in all of Europe.

Above the façade of the theatre rests a sculpture of the Spanish coat of arms under Franco. The yoke and arrows (el yugo y las flechas) were the symbols of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic Monarchs who united Spain as one kingdom. These symbols were included in the coat of arms of Spain from 1492 to 1504 and then from 1938 to 1981. The Falange, the official (yet still somewhat marginalized) political party of the Franco regime, used a stylized yoke-and-arrows as their official emblem.

The Poor Clares doing the laundry in the lower part of their convent. The circular convent (below) was located towards the rear of the Laboral, and featured an open loggia looking out over the nuns’ garden.

Teachers at the café bar.

The Universidad Laboral’s cows pose to have their picture taken.

Unfortunately, with the death of Franco and the subsequent transformation of the Spanish state, all the Universidad Laborals began to suffer from neglect. The Jesuits handed over control of the Gijón school to the faculty in 1978. Originally funded by the trade unions, they became part of the state-run National Institute for Integrated Education in the 1980s. Shortly afterwards, the Poor Clares were kicked out of their convent. As Luis Moya’s great palace of learning deteriorated, enrollment fell and the Universidad Laboral de Gijón moved to a separate, much smaller campus where it continues today as an “institute of secondary education”.

In 2001, the regional government of the Asturias took charge of the building and its massive grounds. The greater part of the school’s farms were turned into a public golf course. The Laboral itself has been reinvented as a “City of Culture”, its massive complex housing a variety of enterprises. The classrooms now house a campus of the University of Oviedo, where students of business, tourism, and public administration are now taught, as well as the Higher School of Performing Arts. Technological innovations are explored at the Science Park Technology Gijón, while the German multinational ThyssenKrupp has its Spanish headquarters and research & development labs in the Laboral. A hospital is located in the building, and a five-star hotel is due to open in April 2009.

The convent from which the Poor Clares were expelled has been turned into a television studio for RTPA, the regional broadcaster for the Principality of the Asturias.

At least partly in keeping with the original idea, a vocational training center remains at the Laboral’s industrial workshop, with 900 students enrolled.

Deconsecrated, the church that once housed Christ at the center of the Universidad Laboral now serves primarily as a performance venue.

While the departure from its original purpose is to be lamented, at least Moya’s beautiful structure is now being maintained and appreciated after years of neglect. During the interwar period, architects plumbed the depths of modernism with interesting results, but after the war they abandoned the safety of the surface and were submerged into those depths. The results were almost entirely catastrophic. Luis Moya, and a number of the other Spanish architects favored under the Franco regime, present a convincing counterargument.

The Universidad Laboral presents us with an architecture that is a continuation of history, rather than a rejection of history. Its components exhibit a classical symmetry but, like the human body itself, are arranged in a somewhat asymmetrical but nonetheless orderly form. It is the largest building in Spain but is broken up into smaller portions to prevent it from overburdening the inhabitants. It exhibits a natural hierarchy of forms, with the Church at its very heart. The Laboral is proof that there is another way of doing things: that one can be at once modern and traditional. That is a lesson that certainly needs to be understood by architects, but surely also by the rest of society as well.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Very good article that does justice to good architecture, Catholic social justice, and the Franco regime. This large building is a testimony to the balance of design, continuation of tradition with inclusion of modern progress, all under the spirit of the Catholic faith, that today unfortunately is mostly lost in society and in the Catholic Church after Vatican II Council. This monumental building is proof of Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s sense of social justice and progress he bought to Spain after the destructive Civil War that left a million dead. When Franco died in November 1975 the standard of living for the average person had improved greatly. His regime with limited resources and an international boycott until 1954 was successful rebuilding Spain that brought prosperity to all classes. The big move from the country side to urban living took place with higher paying jobs, labor reforms, rural schools, asphalt roads and highways, the tourist industry, dams for irrigation and hydroelectric power, industrialization with a small car totally fabricated in Spain that the working class could afford, social welfare and the rise of a stable middle class, etc. took place under Franco. The benevolent head of state brought peace and order to his nation after the republican regime ( 1931 to 1939 ) allowed and pursued a policy of imposing radical socialism with Communists and Anarchists political factions on the forefront, and open persecution of the Catholic Church. Nationalist patriotic Franco genuinely wanted the best for Spain which the Universidad Laboral de Gijón stands as a monument for anyone with open mind to attest. With its neoclassical architecture and solid construction it has an uplifting ambience with a sense of secure permanence. The magnificent church building at its center is an example of religious tradition in harmony with secular progress and pragmatism. Of state and Church working together for the common good, that was also an important characteristic of the Middle Ages. Therefore, an continuation of Christian Spanish history.

Franco and the movement he led during the Spanish Civil War saved Spain from the evils of Soviet style Communism. It kept it out of World War II despite Hitler’s pressure to join the Axis. Eliminated all revolutionary parties and organizations that was responsible for many of the atrocities committed during the civil war promoted the anti-Catholic leftist revolution. After Franco’s death with the cooperation of younger political leaders that came out of the Franco regime and a younger faction in the Catholic Church after Vatican II the nation was handed over to the political parties and individuals who sided with the revolutionary republic of the 1930s and their ideology. They took control of Spain in the 1980s under PSOE’s Felipe Gonzalez, and today the Left is not interested in upkeeping the achievements of the traditional Catholic Franco regime. A clear evidence is the Ley de Memoria Histórica ( Historic Memory Law ) that attacks Franco and his regime distorting the historic facts to demonize the regime and its leader while white washing tyranny and crimes of the revolutionary forces during the 1930s. In the case of the labor class university unfortunately this socialist agenda is evident in the deconsecration of the church building, the Jesuits gone and Poor Clare kicked out, and general deterioration due to neglect. This demonstrates the hypocrisy of the left, employing a rhetoric to favor the working class, but its actions defy this rhetoric when it neglects an institution created to bring prosperity and uplift the labor class because it was a progressive achievement and benevolent symbol of a conservative traditional Catholic regime that the Left deplores and reminds them of their defeat during the civil war. During my travel and study at the University of Salamanca in Spain during the summer of 2019 I witnessed this policy and attitude of the Left under the government of the socialist PSOE party with the leadership of prime minister Pedro Sánchez. One of the professors of the courses I took on Spanish culture and society, born in the mid 1960s from a family who had fought against Franco’s Nationalists during the civil war, during most of her classes was constantly denigrating Franco and the regime and ignoring all their positive achievements. When I brought up to the class some undeniable facts of these achievements and pointed out that Franco was not the same as Hitler as she had stated to the class, she had no valid arguments and looked somewhat upset. She was very critical of Spain’s traditional history and the traditional Catholic Church. If this is typical of what is being taught today in the schools and universities of Spain no wonder that many of the younger generations lack a realistic understanding of the Franco regime and deplore it as evil. Speaking with three craftsmanship and souvenir store owners in Salamanca, Madrid and Toledo that sold souvenirs of Franco and memorabilia of the regime, they told me the reason why they do not put these items on display on the street windows is due to the Ley de Memoria Histórica that censors any memory of the regime. If these items are not in display inside the stores just ask the owner or employee, and if the owner is Ok selling them he will bring them out for clients to see. The store owner form Salamanca told us when the image of Franco was taken down from the main town square the older generation who lived through the war and those during the regime protested while some leftist youth came to harass the protesters and the police was called in to stop the fighting that broke out with some of the very old veterans of the war striking with their canes the young harassers. It seems that many Spaniards are still fighting the terrible civil war in the hearts and minds. In this respect Spanish society is still divided between Left and Right. In this polarization of society the Left being now in political power and after 45 years of controlling much of the narrative on the civil war and the regime that came out of the conflict has the upper hand. This was obviously visible when in November 2019 the socialist government was able after a long fight with conservative forces and Franco’s family members to get the body of General Franco out of his burial in the Valle de los Caídos, a Cathedral constructed inside a mountain built to burry and honor the death of those who fought on both sides of the civil war, thus bring union and peace to a divided nation. He is now buried in his family’s private cemetery space.

This article on the building structure and history of Universidad Laboral de Gijón is a contribution to understanding and appreciation of what is traditional can coexist in harmony and functionality with the modern. As well as to state accurate historical facts and contribute to an honest narrative for what the regime achieved and stood for.