About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Baron Bossom’s Bridge

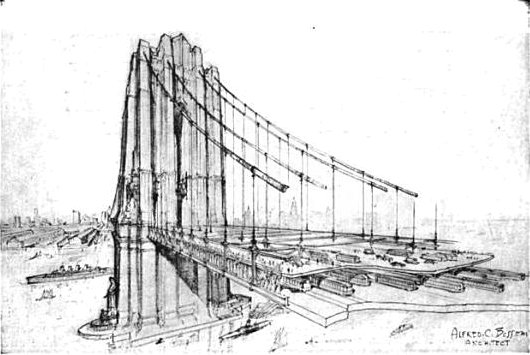

The Unbuilt ‘Victory Bridge’ Crossing the Hudson River at Manhattan

After the victory of America and her “co-belligerents” in the First World War, a temporary victory arch was erected out of wood and plaster to welcome the troops home from Europe. After the arch was dismantled, however, discussions soon arose on how to permanently commemorate the war dead of New York, with a surprising variety of suggestions made. A beautiful water gate for Battery Park was suggested, with a classical arch flanked by Bernini-like curved colonnades, so that a suitable place existed to welcome important dignitaries and visitors to New York. (Little did they know how soon the airlines would replace the ocean lines). Another proposal was for a giant memorial hall located at the site of a shuttered hotel across from Grand Central Terminal, while others suggested a bell tower.

An entirely different proposal, however, was made by the New York architect Alfred C. Bossom (later ennobled as Baron Bossom of Maidstone). Bossom, an Old Carthusian, was an Englishman by birth and eventually returned to his native land, where (in 1953) he gave away the future prime minister Margaret Roberts at her marriage to Denis Thatcher. He himself served in parliament from 1931 until 1959, excepting his wartime Home Guard service. Jokes were often made about his surname resembling both “bottom” and “bosom”. Upon being introduced to Bossom, Churchill jested “Who is this man whose name means neither one thing nor the other?”

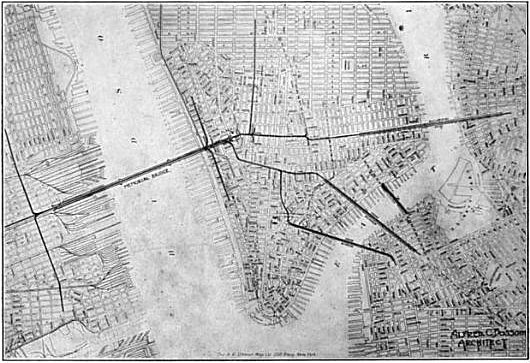

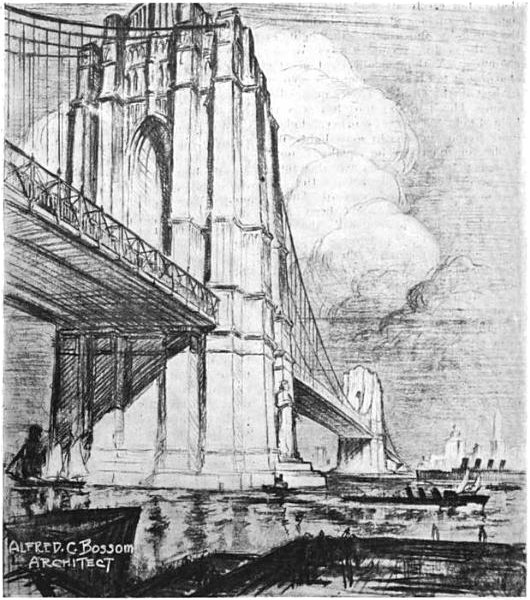

Alfred Bossom envisioned a massive work of engineering and transportation: a ‘Memorial Bridge’ spanning the Hudson at Manhattan. As memorials go, however, it was suggested that the ‘Memorial Bridge’ was too large, too impersonal, and too utterly convenient as a public work to serve as a memorial to the dead, and so Bossom promptly rebranded his idea as the ‘Victory Bridge’. The floor of the bridge was described as very high, in accordance with the requirements of the War Department for ocean-going vessels to pass beneath it, but also allowing the New Jersey side to rest upon the heights of Weehawken. The lower level was to hold ten railway tracks side-by-side.

The bridge would arrive at Manhattan with three approaches to East River bridges nearby, to facilitate movement to Brooklyn and Long Island. While Bossom’s bridge was never built, the siting was obvious an appropriate one, as the Holland Tunnel was later constructed emerging at the same point Bossom chose for his bridge.

“Who has not felt his imagination kindle,” Robert Imlay wrote in the Architectural Record, “as he crossed a great bridge suspended over the mouth of a river at a huge port, its water teeming with great ships from all the harbors of the seven oceans, and little craft; its banks lined with splendid docks, behind them towering the skyline of a city? To a myriad of humans that traverse the East River Bridges each day, the trip is always an event which lifts them a little above the materialism of life. Is not this exaltation just the impression that a monument of victory should give? There is no better symbol for a memorial than a tower, and the two huge pylons, designed by Mr. Bossom, that support the suspension cables, are intended to give the memorial character inseparable from a bridge of victory—one tower devoted to New York and one to New Jersey, and to be used for no other utilitarian purpose than their function of supporting the cables. Such towers are fit memorials, both in their splendid monumental architecture and in their incomparable position astride a great river where it enters the sea—the portals of a huge city and of two states.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Nifty bridge. Prettier than the GWB, though IIRC that was supposed to be stone-clad as well but the money ran out.

Indeed, Cass Gilbert was supposed to design the two towers of the George Washington Bridge.

I find it a bit too much; I prefer the GWB plans (the stone clad ones). There’s a model in the lobby of one of the Smithsonian museums, forget which, probably the Museum of American History.

Very interesting! From the windows of my office here in downtown Dallas, I have the pleasure of overlooking Bossom’s Magnolia Petroleum building and a corner of his addition to the Adolphus Hotel. Mr. Cusack, you never cease to provide enlightening posts. Thanks again.

Beautiful! I’m doing research on some of the architects of NC and came across Bossom’s work on the facade of the Charlotte National Bank (it was razed and the facade put on the 1986 building. Tucson did something similar with the facade of the second Catholic cathedral when it was razed, now on our AZ Historical Museum. The stone work was numbered and saved in someone’s backyard for several years.) Don’t know much about Bossom’s work, but from what I’ve seen, remarkable! Thanks for a great site!

Forgot to mention, I wasn’t aware of his involvement with FLW on the Imperial Hotel. My great-great grandfather was the structural engineer on the hotel and told my grandfather that Frank was a bear to work with. Great architect though!

Did Bossom publish the proportions, too? For it to effectively allow ocean liners to pass under it, it would have to be at least 200 feet off the water.