About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

City Hall Post Office

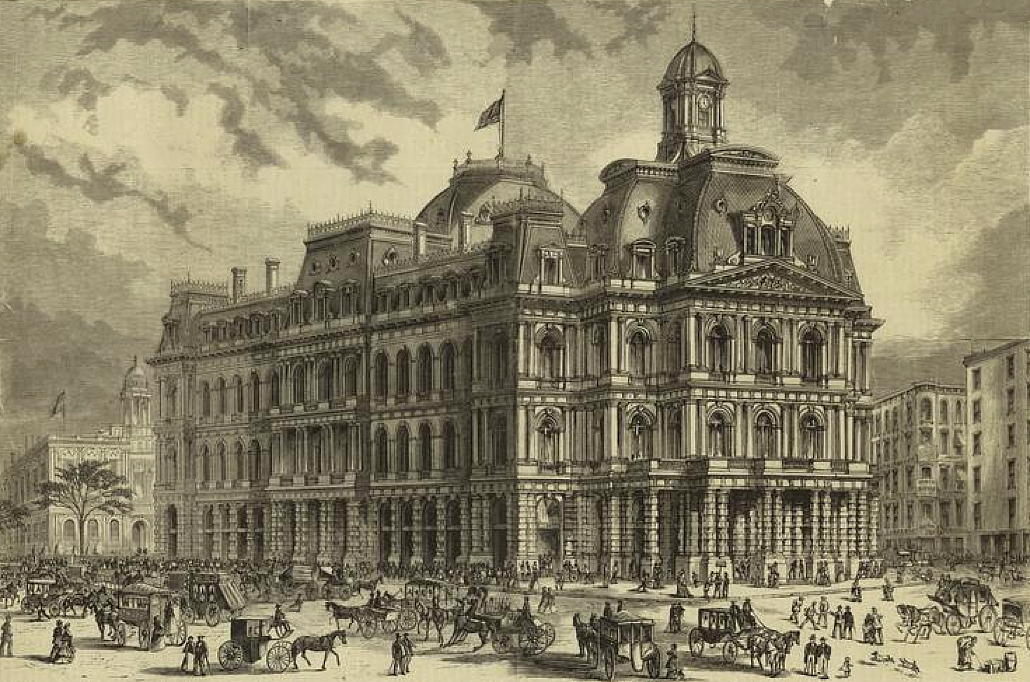

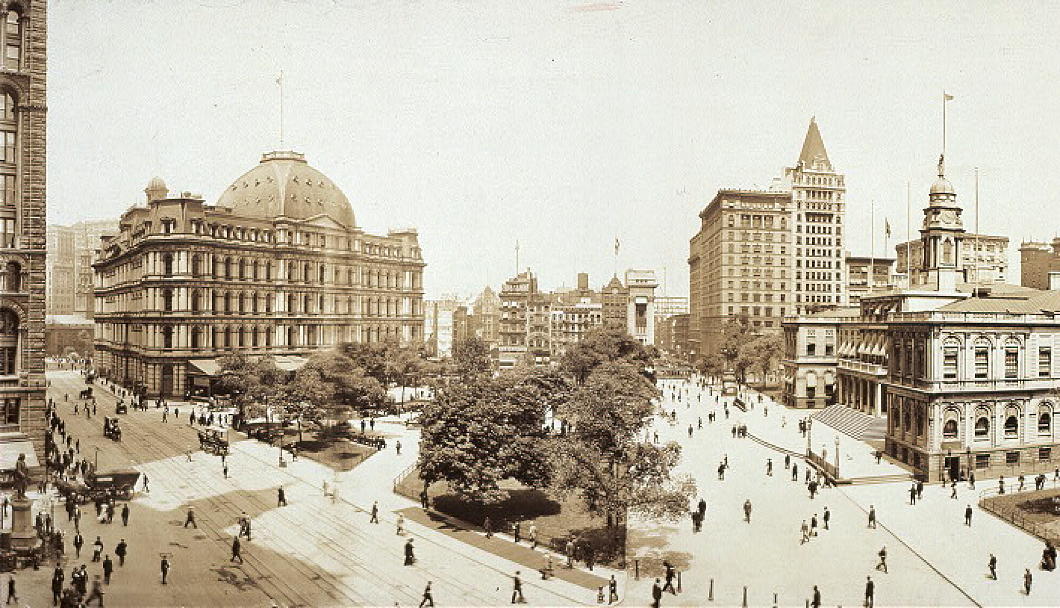

New York’s Lost Second Empire Gem

The Second Empire as an architectural style in America has always bad rap. The most prominent example in the New World is the Old Executive Office Building next to the White House in Washington, D.C. — formerly known as the State, War, and Navy Building after the three government departments it housed in the days of a slimmer federal state.

The OEOB was designed by Alfred B. Mullett, a Somerset-born architect who had immigrated to the United States when he was eight years old. Mullett trained as an apprentice under Isaiah Rogers who was Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury Department. In practice, the Treasury’s architect designed all the American federal government’s office buildings across the Union, and Mullett inherited the job in 1866.

At that time, the ever-expanding city of New York was desperately in need of a new post office, having occupied the former Middle Dutch Church since 1844. Congress approved funds for a new building, and an architectural competition attracted fifty-two entries. Instead of choosing one of the entries, five leading contenders were selected to collaborate on producing a single design.

Mullett criticised the joint design as too expensive and called in the job to his own office so that he could design the building himself.

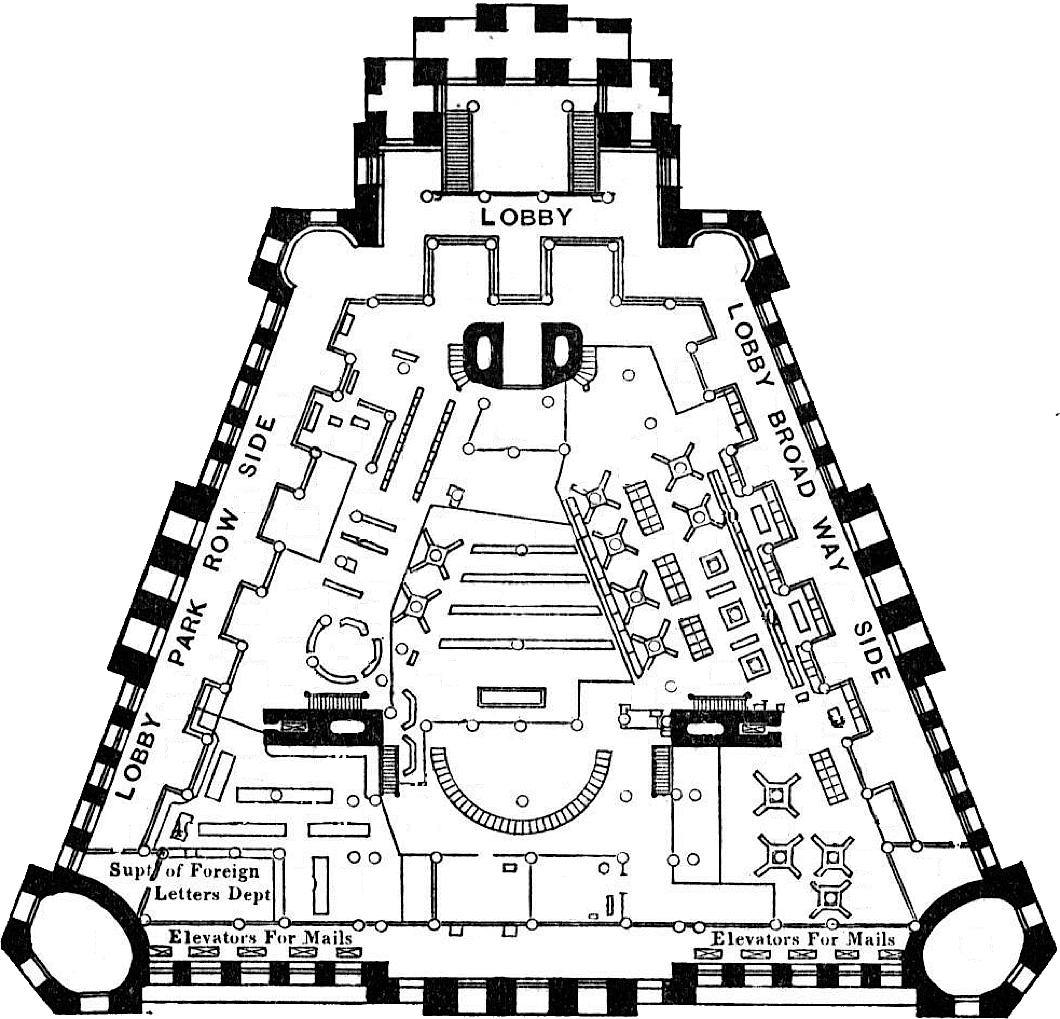

Mullett’s Second-Empire design provided for a post office open to the public on the ground floor, mail sorting rooms below it, and space for federal courtrooms as well as offices for federal agencies in the floors above the postal facilities.

The original design (above) called for only four storeys but during the design process the need for more space to serve the growing city moved Mullett to slip another floor in beneath the mansard roof.

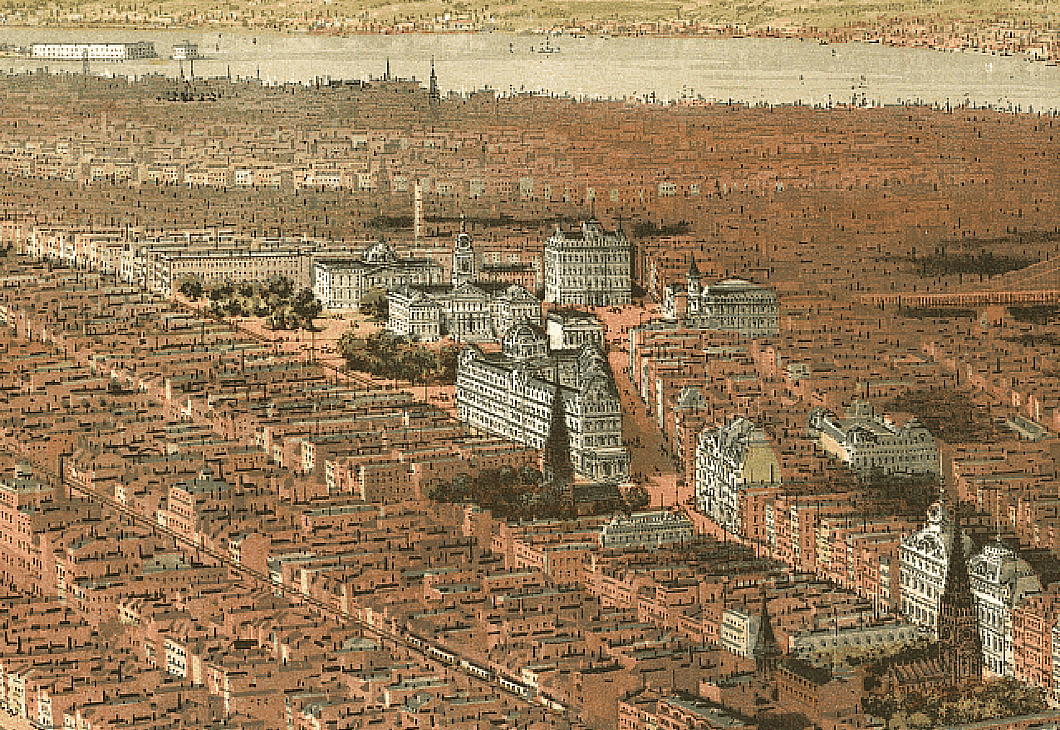

The location was a central one: the City of New York sold a triangular site at the bottom of City Hall Park to the Federal Government for half a million dollars — the exact limit authorised by Congress.

The triangle pointed south down Broadway, with the apex adjoining the colonial-era St Paul’s Chapel and the flat north face looking across the park to New York’s City Hall.

Ground was broken for the project in 1869 but construction dragged on for years. Mullett defended himself from charges of incompetence after three workers were killed in an accident on the site in 1877. By 1880, the City Hall Post Office and Courthouse was finished and open for use.

Some praised the design of this high-Victorian lady with its prow pointing proudly down Broadway, but others labelled it ‘Mullett’s Monstrosity’. The excessive cost of the building — $8.5 million when the budget called for $3.5 million — also sparked criticism against its architect.

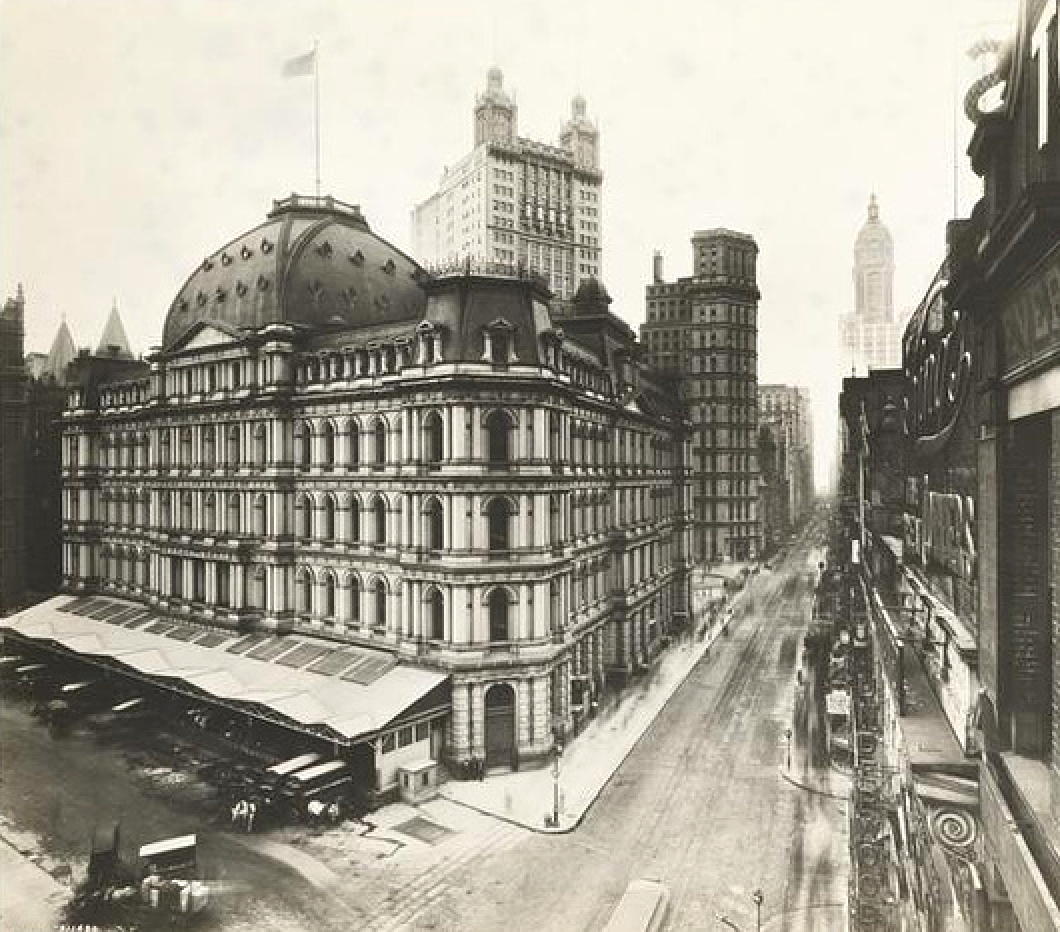

The siting of postal loading docks — later protected from the elements by an artless canopy — facing directly on to City Hall Park was widely denounced and by the time the building was completed (late) its architectural style was already going very quickly out of fashion.

It didn’t work out too well for Mullett. Criticism of this and other projects mounted, and a reform-minded Treasury Secretary initiated an investigation. It was all too much for the architect who had built forty major projects for the federal government. After failing at his own private practice, Mullett killed himself in Washington in 1890.

Nathan Silver, the author of the obligatory classic Lost New York, found the building worth a re-assessment of the initial criticisms.

“Its most compelling trait was the way the Post Office played against City Hall,” he argued.

“The Post Office served to enclose the south side of City Hall Park, and even the mistake of having the loading docks on the north side of the Post Office did not spoil the principle of the neat urban square.”

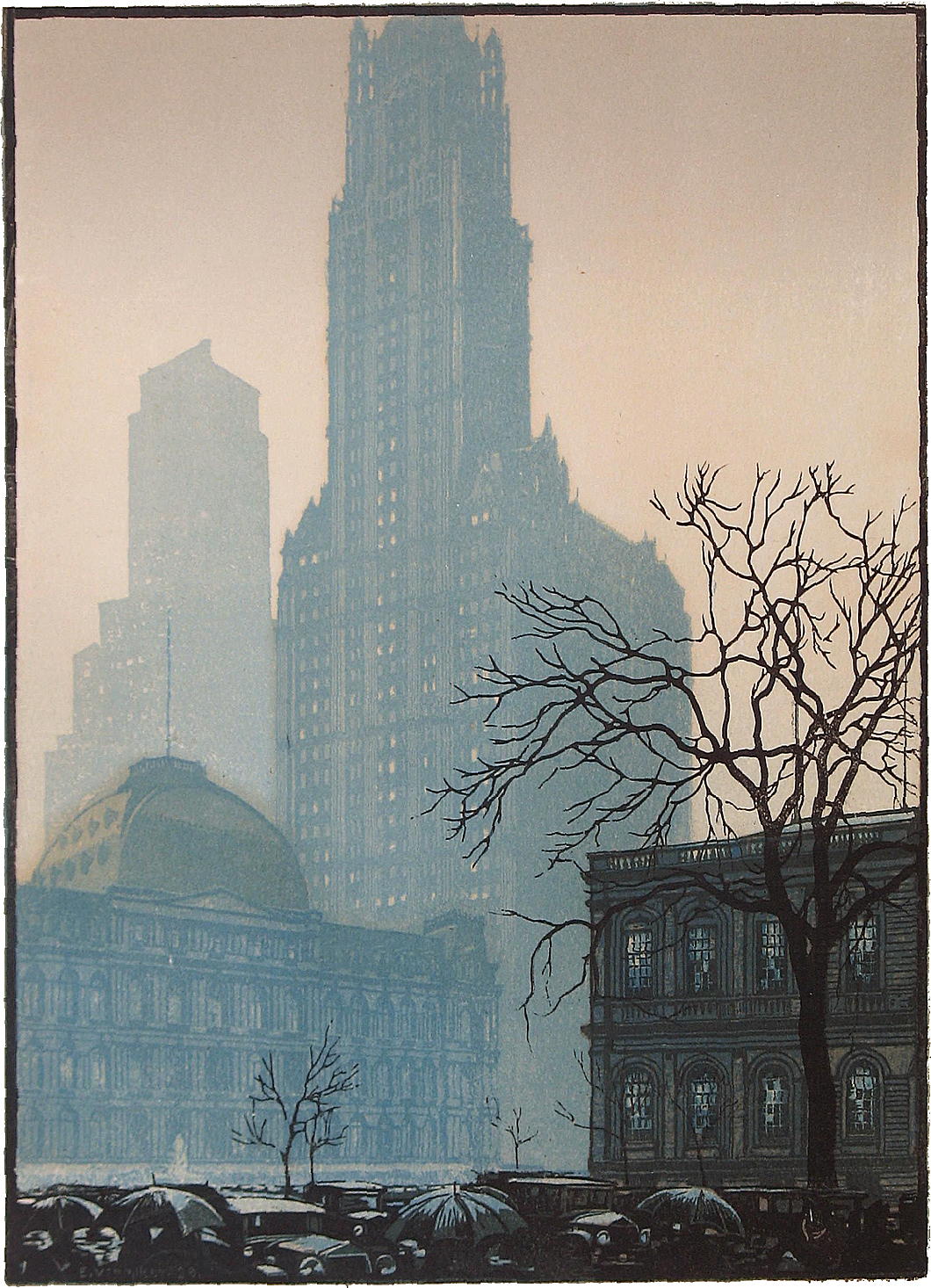

“When Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Tower was built,” Silver continues, “the Post Office not only made it seem taller, but it kept City Hall from appearing as an isolated dwarf”.

By the 1890s it was already clear that the United States Post Office would require a much larger facility to handle New York City’s mail, and McKim Mead & White were chosen to design the General Post Office across the street from the classical temple of Pennsylvania Station.

The federal courts found the building too cramped for their expanding needs and moved out to the beautiful menagerie of classical buildings at Foley Square in 1932.

The New York Times led the charge for the building to be razed to the ground, calling it an “architectural abomination”. Even the New-York Historical Society called for it to go.

The City looked forward to hosting the 1939 World’s Fair and thought demolishing the Post Office would be an act of beautification, returning the site to its earlier role as part of City Hall Park.

Unloved, its demolition was completed over the winter of 1938-39.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Bicycle Rack April 29, 2024

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Another great post!

Personally, I think it was a loss, but what stands out to me in most of those pictures is the Singer Sewing Machine Building in the background- which I admired as a child.