2024 March

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Patrick in Parliament

The Mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Palace of Westminster

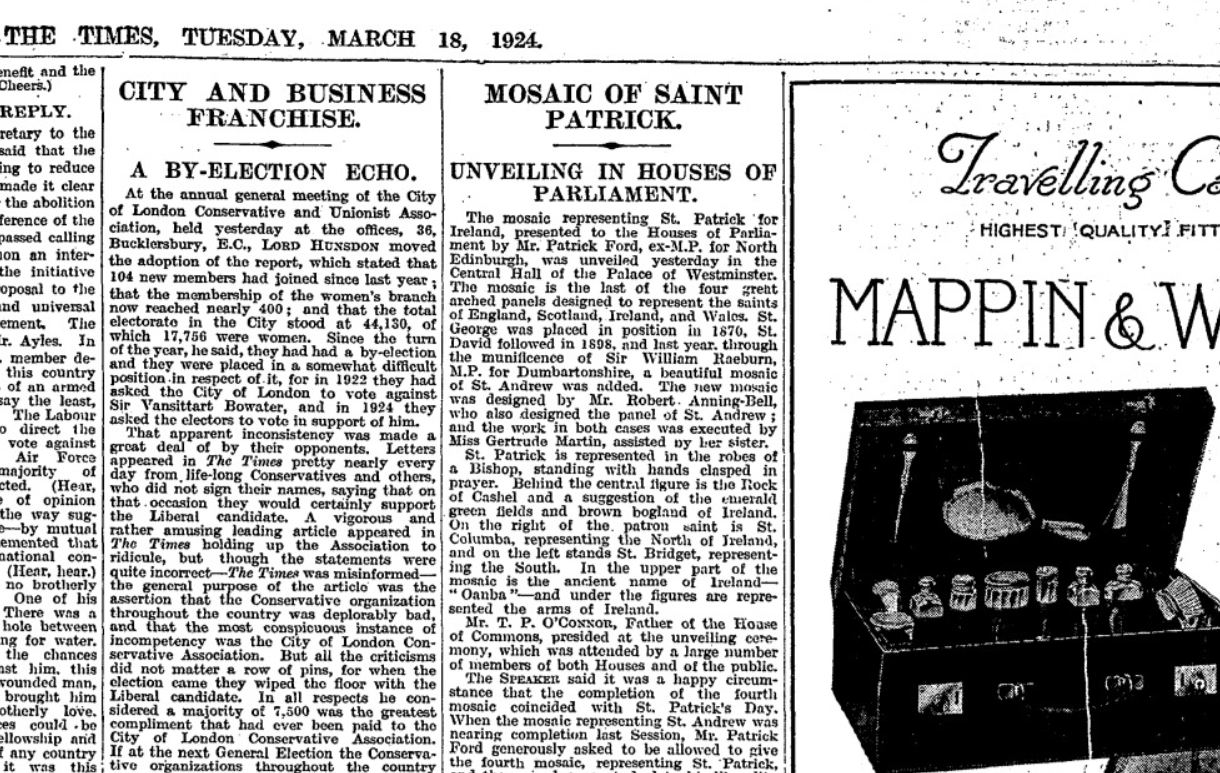

This feast of St Patrick marks the hundredth anniversary of the mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Central Lobby of the Houses of Parliament. At the heart of the Palace of Westminster, four great arches include mosaic representations of the patron saints of the home nations: George, David, Andrew, and Patrick.

The joke offered about these saints and their positioning is that St George stands over the entrance to the House of Lords, because the English all think they’re lords. St David guards the route to the House of Commons because, according to the Welsh, that is the house of great oratory and the Welsh are great orators. (The English, snobbishly, claim St David is there because the Welsh are all common.) St Andrew wisely guards the way to the bar (a place where many Scots are found), while St Patrick stands atop the exit, since most of Ireland has left the Union.

The mosaic of Saint Patrick came about thanks to the munificence of Patrick Ford, the sometime Edinburgh MP, in honour of his name-saint. Saint George had been completed in 1870 with Saint David following in 1898.

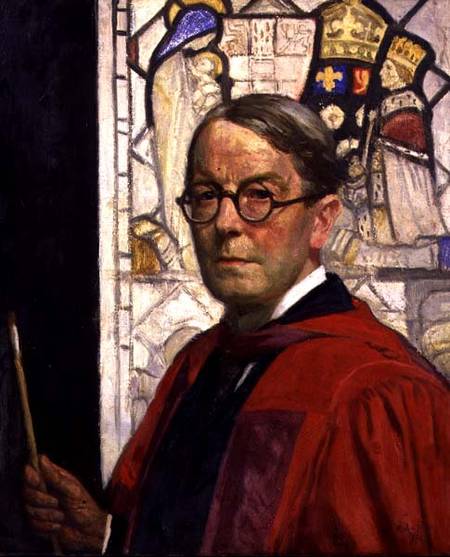

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Anning Bell had earlier completed the mosaic on the tympanum of Westminster Cathedral from a sketch by the architect J.F. Bentley. Following his work in Central Lobby he also did a mosaic of Saint Stephen, King Stephen, and Saint Edward the Confessor in Saint Stephen’s Hall — the former House of Commons chamber.

In the mosaic, Saint Patrick is flanked by saints Columba and Brigid, with the Rock of Cashel behind him. As by this point Ireland had been partitioned, heraldic devices representing both Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are present.

On St Patrick’s Day in 1924, the honour of the unveiling went to the Father of the House of Commons, who happened to be the great Irish nationalist politician T.P. O’Connor, then representing the English constituency of Liverpool Scotland (the only seat in Great Britain ever held by an Irish nationalist MP).

“That day,” The Times reported T.P.’s words at the unveiling, “in quite a thousand cities in the English-speaking world, Saint Patrick’s name and fame were being celebrated by gatherings of Irishmen and Irishwomen. Certainly he was the greatest unifying force in Ireland.”

“All questions of great rival nationalities were forgotten in that ceremony. From that sacred spot, the centre of the British Empire, there went forth a message of reconciliation and of peace between all parts of the great Commonwealth — none higher than the other, all coequal, and all, he hoped, to be joined in the bonds of common weal and common loyalty.”

T.P.’s remarks were greeting with cheers.

The Most Honourable the Marquess of Lincolnshire, Lord Great Chamberlain, accepted the ornamental addition to the royal palace of Westminster on behalf of His Majesty the King.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

Cambridge

There’s a Dutch vibe to Cambridge that I rather like — but also a lingering Protestant Cromwellianism that I don’t. These two factors are not unconnected, and the highway that once was the North Sea is not so far away.

It is not a bad town. It’s like they took Oxford apart, put it back together again in not quite the same way, and added a lot of Regency infill. Oxford is more mediaeval, Georgian, and neo-mediaeval, whereas Cambridge is mediaeval, Tudor, and Regency.

The Cam is slower, quieter, and more peaceful than the Isis, which again gives it the quality of a Hollandic canal. I suspect the punting is better — or at least easier — here than at Oxford.

And of course it is rather more spacious than Oxford, which is hemmed in by geography in a way that Cambridge isn’t.

But it is also eerily quieter. A smart restaurant on a Thursday night was dead by half ten, and the staff refused our plaintive request for a second round of Tokay. (Protestantism.)

Taken on Trust

There is much talk these days of the nature of “high trust” societies and the many benefits which they bring, or once brought in the case of countries like Great Britain that, until relatively recently, fell into this category.

The young Lee Kuan Yew (1923-2015) was astounded when he exited the Underground station at Piccadilly Circus and saw a pile of newspapers and a box of coins and notes, with passers-by being trusted to pay for their own newspaper and calculate their own change. He determined that Singapore must emulate the high trust society that Britons had inherited.

In his excellent book, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory 1793-1815, about the logistics of Britain’s fight against Old Boney, Roger Knight writes of how much trade and agriculture across Great Britain relied upon this trust.

Drovers, for example, would take on thousands of pounds worth of animals — pigs, cattle, etc. — from farmers to drive down to London en masse, not returning for weeks, and usually with little or no paper record.

Citing Bonser’s The Drovers: Who They Were and How They Went, An Epic of the English Countryside, Knight relays the following story:

Perhaps the most impressive demonstration of trust was the tradition of dogs being sent home to Scotland or Wales from London on their own. One story involved a Welsh dog named Carlo who journeyed all the way back to Wales from Kent. His owner sold the pony that he had ridden on the outward journey, intending to go home by coach. He fastened the pony’s harness to the dog’s back and attached a note to it, addressed to each of the inns on the route they had followed, to request food and shelter for the dog, to be repaid on a subsequent journey. Carlo reached home in Wales alone in a week.

Even dogs benefited from a high-trust society.

Immanuel on the Green

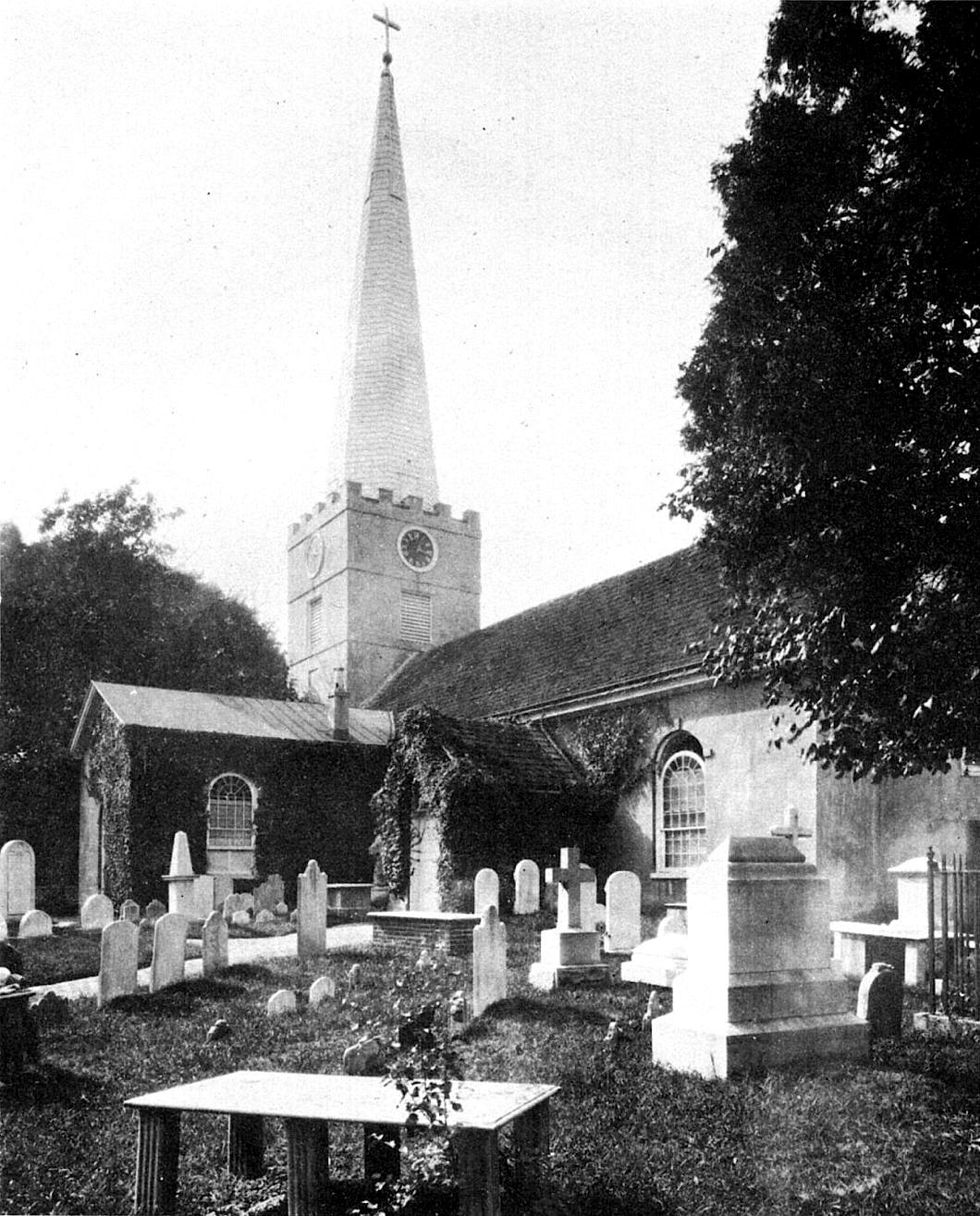

The prettiest situated church in the little state of Delaware

In the old Delaware hundred of New Castle on the town green sits the Immanuel Protestant Episcopal Church — the first Church of England parish in what is now the State of Delaware. This part of the world started out as New Sweden, but our Dutch forefathers of old, settled as they were in New Amsterdam, quickly took umbrage at the Scandinavian presence in what they viewed as a distinctly Netherlandic domain.

By the time Sweden and Poland went to war in 1755 — a conflict, confusingly, called the Second Northern War by some and the First Northern War by others — a Polish citizen of New Amsterdam had convinced the governor, Peter Stuyvesant, to let him take a team to go and establish a Dutch fort in the lands claimed by the Swedes. Stuyvesant named the settlement Fort Casimir after the many legendary Polish kings to bear that name, as well as the reigning King of Poland at the time, John II Casimir.

The dastardly Swedes captured Fort Casimir in 1654, led by an Östergötlander by the name of Johan Risingh. (As it happens, Rising had studied at Leiden in the Netherlands in addition to his native land’s university of Uppsala.) The Swedes had seized the fortress on Trinity Sunday, and so they rechristened it as Fort Trinity — or Fort Trefaldighet in their own tongue.

Stuyvesant was forced to lead an expedition himself to kick the Swedes out and, after a scrap that went down as “the Most Horrible Battle Ever Recorded in Poetry or Prose”, he returned to Dutch Manhattan in triumph.

“It was a pleasant and goodly sight to witness the joy of the people of New Amsterdam at beholding their warriors once more return from this war in the wilderness,” no less a source than Diedrich Knickerbocker recounts.

The schoolmasters throughout the town gave holiday to their little urchins who followed in droves after the drums, with paper caps on their heads and sticks in their breeches, thus taking the first lesson in the art of war. As to the sturdy rabble, they thronged at the heels of Peter Stuyvesant wherever he went, waving their greasy hats in the air, and shouting, ‘Hardkoppig Piet forever!’

It was indeed a day of roaring rout and jubilee. A huge dinner was prepared at the stadthouse in honor of the conquerors, where were assembled, in one glorious constellation, the great and little luminaries of New Amsterdam. … Loads of fish, flesh, and fowl were devoured, oceans of liquor drunk, thousands of pipes smoked, and many a dull joke honored with much obstreperous fat-sided laughter.

But the joyous dominion the Hollanders held over the former Swedish territory was to be short-lived. By fate and the divine hand, the Duke of York — later our much beloved and since departed majesty King James II — seized New Amsterdam without firing a shot in 1664 and New Netherland became the Province of New York overnight.

Down on the banks of the Delaware, the Dutch-founded Fort Casimir, re-consecrated as Fort Trinity by the Swedes, had returned to Dutch control under the name of Nieuw Amstel. The English now named it New Castle, a name which has stuck ever since.

By a livery of seisin, the Duke of York transferred this part of his fiefdom to William Penn in 1680, who went and founded Pennsylvania a year later. But the English, Dutch, and Swedish inhabitants of “the lower counties on the Delaware” bristled under the dominance of the culturally distinct Quakers. They petitioned the Crown to be governed by a separate legislature, which privilege was duly granted in 1702.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories