2019 February

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

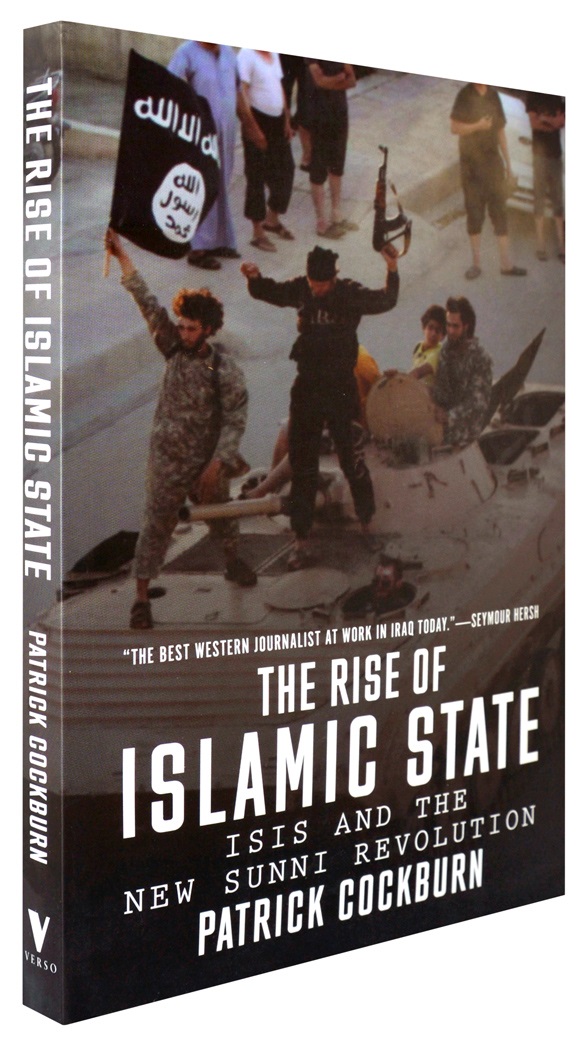

The Dawn of Da’esh

Patrick Cockburn, 192 pages, £9.99 (Verso Books, London)

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

Much of the novelty of ISIS lies in the suddenness of their appearance and the continuous string of victories they have amassed. Cockburn is quick to point out that much of this is propaganda: ISIS has been a player in the region for years, but mostly as an authorised bin Laden franchise founded by the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and under the name of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Following al-Zarqawi’s death, the Sunni jihadist group transformed into the Islamic State in Iraq and proclaimed its new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi the ‘emir’, expanding operations into Syria by 2013.

Despite numerous successful terrorist attacks and assassinations, it is the capture of Mosul in June 2014 which Cockburn singles out as the start of ISIS as the phenomenon we are experiencing today. This stellar rise has yet to prove fully meteoric in the sense that, while their onward march has ground to a halt at Kobane, ISIS has stubbornly refused to burn out and fade away. This has been contingent upon an alignment of factors which might be oversimplified into three: the endemic corruption of the Iraqi state, the astounding stupidity of Western powers, and the entrenched sectarianism of Iraqi society.

As one of the most central institutions of the state, the melting-away of the Iraqi Army’s resistance to ISIS has been crucial. It is difficult to overestimate the vast scale of corruption in the Army. Military units often include large numbers of troops that exist only on paper. Command of a division comes with a high pricetag. Having borrowed the money to pay for it, divisional commanders then require steady income streams to pay back the loan. Setting up roadblocks to extort money from travellers is an easy task for an armed force, but the possibilities are numerous.

A retired Iraqi general tells Cockburn the rot first set in when, in 2005, the Americans demanded the Iraqi Army outsource food and logistical supply:

“A battalion commander was paid for a unit of 600 soldiers, but had only 200 men under arms and pocketed the difference, which meant enormous profits.”

In Mosul, Cockburn points out, only one in three of the soldiers meant to be there were physically present, the rest having payed up to half their salaries to be on permanent leave.

Endemic corruption of this kind has been fostered by the complacency of the governing elite. A Turkish businessman was ruffled when a local ISIS leader demanded $500,000 per month in protection money. “I complained again and again to the government in Baghdad,” he relates to Cockburn, “but they would do nothing about it except to say that I should add the money I paid to al-Qaeda to the contract price.” Such an attitude hardly inspires confidence in the state.

As ISIS gained ground across Iraq, the Baghdad elite seemed only to increase its insularity, acting as if nothing was wrong. “When you speak to any political leader in Baghdad,” an ex-minister says, “they talk as if they had not just lost the country.”

“ISIS,” Cockburn points out, “are experts in fear.” YouTube has been deployed with a methodical exactness towards this end. The talking heads who’ve preached the gospel of new media as breaking down barriers and leading to an immanent global liberation have plainly failed to grasp that these new forms of communication can be expertly employed by forces intrinsically opposed to their vision of a liberal utopia.

While the Shi’ites have long been in the majority, the Sunnis were top-dog under Saddam, widely favoured and occupying places of power and authority. With Saddam toppled and democratic elections now forming the basis of the state’s legitimacy, the numerical strength of the Shia has handed the state to Shi’ite political forces fearful of a return to the old days. When Sunnis complain of violence, intimidation, and discrimination at the hands of the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, Shi’ites don’t see the Sunnis as reacting to oppression but as plotting a return to their former dominance.

This de-legitimisation of the official state in the eyes of Sunni Iraqis has provided the space in which the zealous ISIS has come to the fore. Where ISIS rules it is widely unpopular – in a country of smokers, Cockburn notes, they have demanded bonfires of cigarettes in captured towns – but too many of ISIS’s enemies are opposed to all Sunnis, not just ISIS. This means Sunnis opposed to ISIS have no one to turn to for protection or support. All too many have calculated that enforced piety and oppression from ISIS are preferable to being murdered by Shia militiamen in police uniforms just for being Sunni.

But one of the most influential factors in the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq has been events in neighbouring Syria. Shifting his aim westwards, Cockburn provides analysis of events that is both illuminating and frustrating. The interference of external powers in Syria, whether Middle-Eastern or Western, has had catastrophic and usually counter-productive effect. In the midst of a supposed ‘global war’ on Islamic terror, the logic of toppling yet another bastion of Ba’athist-style dictatorial secularism in the region is murky. Encouraging a Sunni uprising in Syria without foreseeing a knock-on effect in neighbouring Iraq also strikes Cockburn as particularly naive.

The vitality of continued opposition to Assad by the US-led Western powers and by states in the region is astonishing – almost satanic. The United States happily allied itself with the most murderous force in the twentieth century – the USSR – in order to defeat the more pressing evil of Nazi Germany. And yet the exponentially milder Assad regime is somehow considered totally untouchable – or ‘haram’ as the locals of the region might say. It was only twenty-odd years ago Syrian troops were fighting as part of the US-led coalition in the First Gulf War. The transformation since then is inexplicable (and, with his hands already full, Cockburn does not attempt to offer any insight into this).

Despite the severity of the civil war being waged in Syria, the West has demonstrated openly and brazenly that it is more interested in eliminating Assad than ending the war. As Cockburn frequently points out, Assad has continuously been in control of all but two regional capitals in Syria, yet the United States says he can’t even have a place at the negotiating table unless he agrees to give up power. That’s not a pre-condition: it’s a repudiation. Failed politicians in this part of the world don’t retire to bank boards and book deals like in the West – more often their bloodied corpses are dragged from their palaces by a mob of well-orchestrated ferocity. (The victors’ justice of Saddam’s execution is a rare example that tests the rule.)

Laying the Assad-must-go precondition is a bold statement by Western powers that they grant zero priority to ending the war. Despite all their high-minded liberal humanitarian cover talk, it’s simply not on the agenda: Power is the only thing.

Despite the unsurprisingly depressing subject matter, the author is persuasive in his clear and cogent writing. This book—and Cockburn’s reporting more generally—is helpful both to those with some familiarity with the region and total novices in deepening one’s understanding of a situation that defies adjectives.

As bombs were falling on Libya, Cockburn pointed out the jihadist nature of many of the rebel groups in the north African country, only to be confronted by an American reporter: “Just remember who the good guys are.” For those looking to avoid the Manichean oversimplifications we are too often fed, this book is a welcome and insightful reprieve.

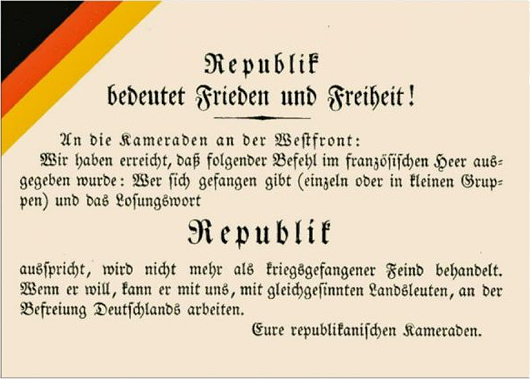

Weimar’s Black, Red, and Gold

In fact, there was a great deal of overlap between these two sides, and in the most recent Junge Freiheit Dr Karlheinz Weißmann explains how the troubled Weimar Republic made its choice of national symbols.

The colours of the Republic

by Karlheinz Weißmann — Junge Freiheit 18 February 2019

(slapdash unofficial totally unauthorised translation)

At the end of December 1918, Harry Graf Kessler noted confusedly in his diary that supporters of the [liberal republican] German Democratic Party (DDP) had marched through the centre of Berlin, with the “Greater German colours” black-red-gold and singing Der Wacht am Rhein.

In fact, the left-wing liberals were the only political group next to the Völkisch movement who had clung on to the black-red-gold. For both of them, it was about the ideal of an all-German state, including the Austrians. For the Liberals, it also represented the ideals of the revolution of 1848, while for the Völkisch there was the idea that black, red, and gold were the ancient Aryan colours.

During the period of downfall in 1918 it wasn’t the black-red-gold that mattered: it was the red of the socialists. Majority and Independent Social Democrats as well as the Communists all used it as a symbol. Red armbands, red cockades, and red flags marked the followers of the new republic, whose socialist underpinning was generally believed.

Black-red-gold as last option

By contrast, the old imperial colours of black-white-red almost disappeared. Significantly, the naval mutineers in Kiel had barely raised a hand to defend them. But the soldiers returning home from the front marched under black-white-red flags — which they had made themselves — and were received in the cities, even in Berlin, with black-white-red flags and decorations. The newly established Freikorps also deployed the old imperial colours, as did the cockade of the new Reichswehr whose ranks included many opposed to the republican order.

With this juxtaposition of revolutionary red and the black-white-red of tradition, black-red-gold — Schwarz-Rot-Gold — came as the last option. Some hoped that, on the one hand it would stand for moderation and against total upheaval, while on the other hand it suggested that defeat in the war did not spell the final downfall of the nation.

On 9 November 1918 an organ of the far right, the Alldeutschen Blätter, published an essay entitled “Black-Red-Gold”:

“The birth of Greater Germany is approaching! … Cheer the old black-red-golden colours! Decorate like Vienna your houses with the black-red-golden flags, bows, and bands and show all the world from Aachen and Königsberg to Bozen [Bolzano], Klagenfurt, and Laibach [Ljubljana] that we are a united people of brothers, in no distress of separation or peril.”

Symbol of treason

The 18 February 1919 decision of the State Committee of the Republic to adopt black-red-gold as provisional colours of the Reich was still supported by the expectation that a Greater German Republic would emerge. But the “Anschluss” of Austria was banned at the instigation of the victorious powers and in flagrant contradiction to the right of the self-determination of peoples. This resulted in the first serious discrediting of the black-red-gold.

The second was that black, red, and gold had been reputed to be a symbol of treason since the beginning of the war. A group of deserters and pacifists calling themselves the “Friends of the German Republic” — financed with French money and operating from Switzerland — used the colours for their cause as early as 1915, and as early as the spring of 1918 Entente aircraft distributed calls for desertion and revolution along the western front, marked with a black-red-gold stripe or border.

Almost certainly the majority of the population was relieved when, on instructions from the national government, the workers’ and soldiers’ councils adopted the black-red-gold [replacing the red of revolution] but passive acceptance was not enough to give the colour combination permanent support. This was particularly evident in the peculiar “flag compromise” presented by the government with the support of Majority Social Democrats, the Center Party, and part of the DDP during the deliberations of the National Assembly.

According to this compromise, the black-red-gold was introduced as the national flag, while the merchant ensign was the old black, white, and red — albeit with a small black-red-gold flag infelicitously shoved in the canton. Interior Minister Eduard David’s rationale for the choice — that the old colours had been “party” rather than “national” colours — simply did not correspond to fact.

Symbol of Greater Germany

Closer to the truth was the justification that black, red, and gold were the symbols of a Greater Germany. Interior Minister David said:

“What dynastic Germany could not do, democracy must succeed in doing: achieving moral conquests beyond the frontier and, above all, among those who by blood and language belong to us. To win the Greater German unity must now be our goal, not through war and violence, but through the recruiting power of the new republican Germany, and let us fly forward in front of the black-and-red-gold banner!”

In any case, Article 3 of the Weimar Constitution, which entered into force on 11 August 1919, was far from providing a sound answer to the flag question of the young state. As constiutional scholar Ernst-Rudolf Huber wrote:

“This Weimar flag compromise became the cause of endless strife. If the constitutional function of state colours exists in their symbolic power to integrate the state’s unity, the state-sanctioned dualism of contrasting colours manifested in the Weimar flag compromise is a permanent element of disintegration. The flag compromise, with its juxtaposition of the old and new colours, did not diminish the problem of the colour change but rather aggravate it.”

The Feast of St Valentine in the Cape

Die fees van Sint Valentyn in die Kaap

A nice tradition!

’n Lekker tradisie!

In quotidianis disputationibus clarus

The indispensable Canadian disputationist David Warren wrote a piece mentioning Sudharma, the only newspaper printed in Sanskrit, the “dead” language of ancient India. It reminded me of the story of when someone asked Borges if he knew any Sanskrit. “Only the Sanskrit everyone knows,” was the Argentine’s response.

Anyway, given that there’s a daily newspaper in Sanskrit, Mr Warren thinks it would be entirely for the good that a daily newspaper be published in Latin.

Why not just publish a good newspaper in English, you ask? (After all, these are severely lacking or perhaps non-existent.) Not enough, Mr Warren argues:

An honest and rational account of what is happening in the world would have to be politically incorrect, in the extreme. People would be outraged, and the ACLU would move to suppress it right away. There would be protests, and attacks by Antifa; racism, misogyny, homophobia, would be alleged. The staff would not be safe to come to work.

Anyone caught reading it near a university would immediately be surrounded by shrieking harpies, and their careers in academia or elsewhere would end. Something like the #MeToo movement would be launched on Twitter, to root these people out.

Whereas, a newspaper in Latin would pass right under the progressive radar. Only those who could read Latin would take it, and almost all of them are mentally stable. Others would be trying to learn Latin, so they could also find out what is going on. Their efforts would contribute to the Catholic underground, where Latin use is spreading.

Expert Latinist Mons. Daniel Gallagher then took to the metaphorical presses of the same inprint to argue that:

Equidem desidero, potiusquam parvam sanitatis insulam, acta diurna praebere quae tot disceptationes ac disputationes provocent quot in lingua Latina, per linguam Latinam atque circa linguam Latinam provocatae sunt per saecula. Haec enim dirigam acta diurna non tantum ad principes verum etiam ad populum ipsum.

By which, in a manner of speaking, he meant:

Rather than offering “a little elitist island of sanity and spiritual calm,” I would want the paper to generate as much lively discussion and debate as always has and always will be generated in, around, and through Latin. I would want to aim the paper at the populus and not just the principes.

And Mr Warren then replies to the reply thus (in item the second).

Go and read all three; they make sound arguments.

II. A Brief to the People – by Mons. Daniel Gallagher (27.I.2019)

III. Two Items – by David Warren (29.I.2019)

Claudia McNeil

As a black Jewish Catholic, Claudia McNeil was pretty much everything the Ku Klux Klan hated. She was born to a black father and a part-Apache mother in Baltimore, Maryland but in her teenage years was adopted by a Jewish family in New York who instructed her in Judaism and taught her fluent Yiddish.

She married aged 19 but lost her husband in the Second World War and both her sons in the Korean War.

After training as a librarian, McNeil drifted into vaudeville theatre and nightclubs, eventually making her Broadway debut in 1953 as Tituba in The Crucible.

“The Jewish faith left an indelible stamp on her spirit,” Ebony magazine reported in 1960, “but she became a convert to Catholicism in 1952.” McNeil often reported that she stopped to pray before every evening’s performance.

Her most famous role was as the matriarch in A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, reprised in the 1961 film in both of which Sidney Poitier also starred.

Deeply appreciative of the gifts God gave her, McNeil was known never to turn down a chance to appear at charity benefit performances, especially for the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress.

Despite the losses she suffered in her life Claudia McNeil insisted “I have everything I’ve ever wanted from life.”

“I have more work than I can do. I have a nice, cheerful, comfortable home. I am solvent. Above all, I have strength, health, and peace of mind. I know where I’m going. I am an American citizen. I love my country. I pay my taxes and vote, and I intend to have a say in how my country is run.”

McNeil retired in 1983 and died ten years later.

Letter to the Editor: The Times

There has been a distinct increase in the number of missives sent out from Huis Cusack to editorial offices across Europe and beyond as part of my slow but inevitable transformation into “Disgruntled of Tunbridge Wells”. It all started with an extremely pedantic letter to the TLS regarding PG Wodehouse, banking, and the collapse of the rupee that was printed in October 2008.

It escaped my notice at the time but it turns out the editors of The Times of London were short of anything decent to print last November so stuck one of my letters in. Very kind of them.

Sir, There is a parallel to the situation of Britons involuntarily losing their EU citizenship: the unionists who fell on the southern side of the border when Ireland was partitioned in 1921. Like the British in Europe today, many Irish then felt themselves secondarily or primarily British or at least strongly associated with Great Britain, given the unitary state which had existed for more than a century. More Irish volunteered their service and their lives for the British crown than ever did for an Irish republic.

As an Irish citizen resident in the UK I appreciate the generosity of spirit whereby Ireland is not a “foreign” country. Irish in Britain today have full civil and political rights above and beyond those of other EU citizens, and this is reciprocated in the Republic (except for presidential elections and referendums).

Were the EU to extend such generosity and reciprocity to the UK after Brexit it would go a long way to furthering our common identity and friendship.

ANDREW CUSACK

London SW3

Of course I am as poblachtánach as anyone else — Up Dev and all that — but one does appreciate the difficulty of those Irish who also identified as British once the Free State was erected. But then given my background (Irish New Yorker educated there, in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa, resident in London) I don’t see any problem with a multiplicity of overlapping identities. All the same, when people imply they will somehow mystically cease to be European come 29 March it just makes them look silly. Great Britain has always been a European country and always will be.

I blame Ulster, the French Revolution, and the Fall of Man.

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories