Catholicism

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A rood-stair pulpit

Among the features of the Church of All Saints in the Forest of Dean village of Staunton, Gloucestershire, is this fifteenth-century stone pulpit.

It is built into a rood-stair that once led to a wooden rood loft, demolished and removed some centuries ago.

This church also has a Norman font thought to have been hollowed out of an earlier square pagan Roman altar.

Benedict of Palermo

The island of Sicily is a cross-section of the numerous kingdoms and empires which have ruled and inhabited it from the Phoenecians down to the present day. During the Norman conquest of the island — those Normans did get around — many Lombards came to help secure the Normans’ rule over the existing Sicilians who were mostly Greek and Arab. The Gallo-Italic dialect of those Lombards is still spoken in a few towns and villages speckled across the island and the settlements they founded are known as the Oppida Lombardorum.

In one such Lombard town, San Fratello, in the 1520s a son was born to an enslaved couple named Cristoforo and Diana whose piety was so highly regarded that their master granted this first-born son, Benedetto (Benedict), his freedom from birth.

From his earliest days Benedict was prone to solitude to the extent that he was mocked by his peers, in addition to being insulted frequently for his black skin. As a teenager he left the family home and became a shepherd but gave whatever he could to help the poor and those even less fortunate than him.

Discerning the call to solitude, Benedict entered the hermitage of Santa Domenica in Caronia but his reputation for holiness was such that the pious people of the island began to visit him and implore him for his prayers and miracles.

Accompanied by another member of the community, Benedict fled to other places around the island, offering great and severe penances in reparation for the sins of humanity, but no matter where he went within days the faithful had found out and pestered him.

When the founder of the hermetic community at Santa Domenica died, the brothers elected Benedict his successor, despite his lack of education and illiteracy. Benedict returned to lead the community until it was abolished in 1562 by the reforms of Pope Pius IV who urged independent groups of Francis-inspired hermits to regularise themselves into existing Franciscan orders.

Benedict went first to a Franciscan friary in Giuliana before settling into that of Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo, the primary city of Sicily. Having been a superior of his old community, Benedict arrived at the Palermo community as a simple cook but even here his piety and talents were recognised. He was first put in charge of the novices and then, in 1578, his confrères elected him their custos or superior though he was only a brother rather than a priest.

He was known as a miracleworker across the island, but it was not only the poor, the sick, and the destitute who flocked to Benedict to seek his help. Theologians and men of learning came to visit this humble and uneducated friar. Even the viceroy of the island was known to take his counsel on important affairs of state.

In his later years, Benedict returned to being the cook of the friary until his death in April 1589. By that time the whole island of Sicily — Greeks, Arabs, Latins, all — revered this poor, humble, and unlettered friar.

Sicily’s ruler, King Philip III of Spain, ordered a magnificent tomb to be built to house Benedict’s remains in the friary of Santa Maria di Gesù, and in death his cult spread far beyond the island.

St Benedict of Palermo — or Benedict the Moor — was beatified by Benedict XIV in 1743 and canonised by Pius VII in 1807. Over the centuries, many non-white Christians came to implore his intercession and he became particularly popular among natives and mixed-race peoples in South America, in Africa itself, and amongst African-Americans in the United States.

This statue is believed to be the work of the Sevillian sculptor José Montes de Oca and was carved in the 1730s. Long in a private collection in Milan, since 2010 it has formed part of the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

Romes that Never Were

When the splendidly named Saint Sturm – Sturmi to his friends, apparently – founded the Benedictine monastery of Fulda in A.D. 742 we can presume he had no idea that the magnificent church eventually erected there (above) would one day be considered for housing the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church.

Rome, caput mundi, is ubiquitously acknowledged by all Christian folk as the divinely ordained location for the Papacy, but this has not always been acknowledged in practice. Most memorable is the “Babylonian Captivity” of the fourteenth century when the papal court was based at the enclave of Avignon surrounded by the Kingdom of Arles. The illustrious St Catherine of Siena was influential in bringing that to an end.

Since the return from Avignon the Successor of Peter has prudently been keen to stay in Rome, but various crises over the past two centuries have seen His Holiness shifted about. General Buonaparte successively imprisoned Pius VI and Pius VII while he made to refashion Europe in his likeness, and the later slow-boil conquest of the Italian peninsula by the Kingdom of Sardinia caused much worrying in the courts of the continents as well.

In 1870, the Eternal City fell to the troops of General Cadorna, and while the Vatican itself was not violated it was widely assumed the papacy could not stay in Rome. Pope Pius IX evaluated several options, one of them seeking refuge from – of all people – the Prussian king and soon-to-be German emperor Wilhelm I.

Bismarck, no ally of the Church, but shrewd as ever, was in favour of it:

I have no objection to it — Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. …

But the King [Wilhelm I] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected. …

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trent.

Bismarck mused to Moritz Busch what a comedy it would be to see the Pope and Cardinals migrate to Fulda, but also reported the King did not share his sense of humour on the subject. The advantages to Prussia were plain: the ultramontanes within their territories and throughout the German states would be tamed and their own (Catholic) Centre party would have to come on to the government’s side.

In the end, of course, the Pope decided to stay put in Rome and became the “Prisoner of the Vatican”, surrounded by an awkward usurper state that made attempts at friendship without betraying its hopes for legitimising its theft of the Papal States. It was the diplomatic coup of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 that finally allowed both states to breathe easy and created the State of the City of the Vatican, an entity distinct from but subservient to the Holy See of Rome.

The Second World War brought its own threats to the Pope’s sovereignty, and the wise and cautious Pius XII feared he might be imprisoned by Hitler just as his predecessor and namesake had been by Buonaparte. Pius was determined the Germans would not get their hands on the Pope and so signed an instrument of abdication effective the moment the Germans took him captive. He would have burnt his white clothing to emphasise that he was no longer the Bishop of Rome.

The record is not yet firmly established but it is rumoured that the College of Cardinals was to be convened in neutral Éire to elect a successor. One wonders where they would have met. The Irish government would undoubtedly have put something at their disposal — Dublin Castle perhaps? Despite the whirlwind of war, the election of a pope in St Patrick’s Hall would have warmed the cockles of many Irish hearts.

But what then? Ireland’s neutrality would have been useful but a German violation of the Vatican’s territory would have been grounds for open, though obviously not military, conflict. Further rumours, also totally unsubstantiated, had it that the King of Canada, George VI, quietly had plans drawn up for offering the Citadelle of Quebec to the Pope to function as a Vatican-in-Exile. Others claim it wasn’t until the 1950s that Quebec was investigated as a possibility by the Vatican in case Italy went communist, as was conceivable.

So Cologne, Fulda, Malta, Trent? None of these plans ever occurred, thank God.

And what about England? Why not? The court of St James and the Holy See, despite obvious and significant differences, enjoyed close relations and overlapping interests in many particular circumstances from the Napoleonic wars until present. Pius IX had put feelers out to Queen Victoria’s minister in Rome, Lord Odo Russell, in 1870 but the British ambassador more or less told him of course the Pope would be welcomed in England but don’t be silly, the Sardinians would never conquer Rome.

One imagines the British sovereign would grant a palace of sufficient grandeur to the exiled Pontiff. Hampton Court would do the job. It’s far enough from the centre of London but large enough to house a small court and the emergency-time administration of the Holy Roman Church. Would the ghost of Cardinal Wolsey plague the Princes of the Church?

Thanks be to God, we’ve never had cause to find out. At Rome sits the See Peter founded and so it looks to remain. Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia.

Wardour

The news from the West Country is that Jasper Conran OBE is selling up his place in Wiltshire, the principal apartment at Wardour Castle.

Wardour is one of the finest country houses in Britain, designed by James Paine with additions by Quarenghi of St Petersburg fame. It was built by the Arundells, a Cornish family of Norman origin, but after the death of the 16th and last Lord Arundell of Wardour the building was leased out and in 1961 became the home of Cranborne Chase School.

A friend who had the privilege of being educated there confirms that Conran’s assertion of Cranborne Chase being “a school akin to St Trinian’s” was correct, and tells wonderful stories of the girls’ misbehaviour.

Alas the modern world does not long suffer the existence of such pockets of resistance, and the school shut in 1990. The whole place was sold for under a million to a developer who turned it into a series of apartments, for the most part rather sensitively done, if a bit minimalist.

The real gem of Wardour, however, is the magnificent Catholic chapel which is owned by a separate trust and has been kept open as a place of worship. Richard Talbot (Lord Talbot of Malahide) chairs the trust and takes a keen interest in the chapel and the building. I was down there the Sunday the chapel re-opened for public worship after the lockdown and Richard was there making sure all was well.

Those interested in helping preserve this chapel for future generations can join the Friends of Wardour Chapel.

Msgr Antony Conlon

IN PREPARING these notes the same response was given by many of Dr Antony Conlon’s friends – “I’ve got lots of stories, but they’re not really suitable for an obituary”. This is in itself an obituary, as it sums up Antony Conlon’s profound sense of fun and friendship; without ever being in the slightest scandalous, yet often hilarious, anecdotes of him are intensely personal. One of his informal nicknames among many of his friends in conversation (more about the other one later) was ‘our mutual friend’ – one knew immediately who was meant, and it reflects his wonderful ability to bring his friends together; there was nothing solitary about Antony Conlon, he lived through and for people.

This quality of openness, while sometimes misunderstood by those who seek clerical detachment in their priests, was an essential part of his priesthood, one which made him deeply pastoral at all times in the everyday world. There was no ‘off-duty Conlon’, even in his lightest moments the same priestly and paternal respect for others was always there, which, paradoxically, attracted non-Catholics to him so readily. His educated and amusing conversation on the widest spectrum of subjects, rarely ‘churchy’, opened the door to everyone.

As one friend said recently, there was never a telephone call, however serious or sad the initial subject, which at some point did not descend (ascend?) to peals of childlike laughter. Even his well-known indignation and fury with those people and institutions he did not agree with (usually because they were opposed to the traditions of the Church or another firmly-held principle) for all their bluster, and the occasional swear-word, were never unkind, and never quite lost sight of human absurdity. (more…)

The greatest church architect you’ve never heard of

The greatest church architect

you’ve never heard of

Ludwig Becker and His Churches

For such a prolific church architect of such high quality, not much is known about Ludwig Becker and, alas, he seems to be little studied. Born the son of the master craftsman and inspector of Cologne Cathedral, Becker had church building in his blood. He studied at the Technische Hochschule in Aachen from 1873 and trained as a stone mason as well.

In 1884 Becker moved to Mainz where he became a church architect and in 1909 he was appointed the head of works at Mainz Cathedral, a position he held until his death in 1940. His son Hugo followed him into the profession of church architecture.

That’s about all I can find out about Becker. But here are a selection of some of his churches, to get a sense of his agility in a wide variety of styles.

St Joseph, Speyer, is my favourite of Becker’s churches for the beautiful organic fluidity of its style. Here Art Nouveau, Gothic, and Baroque are mixed somehow without affectation. Rather enjoyably, it was built as a riposte to a nearby monumental Protestant church commemorating the Protestant Revolt. These two rival churches are the largest in the city after its famous cathedral. (more…)

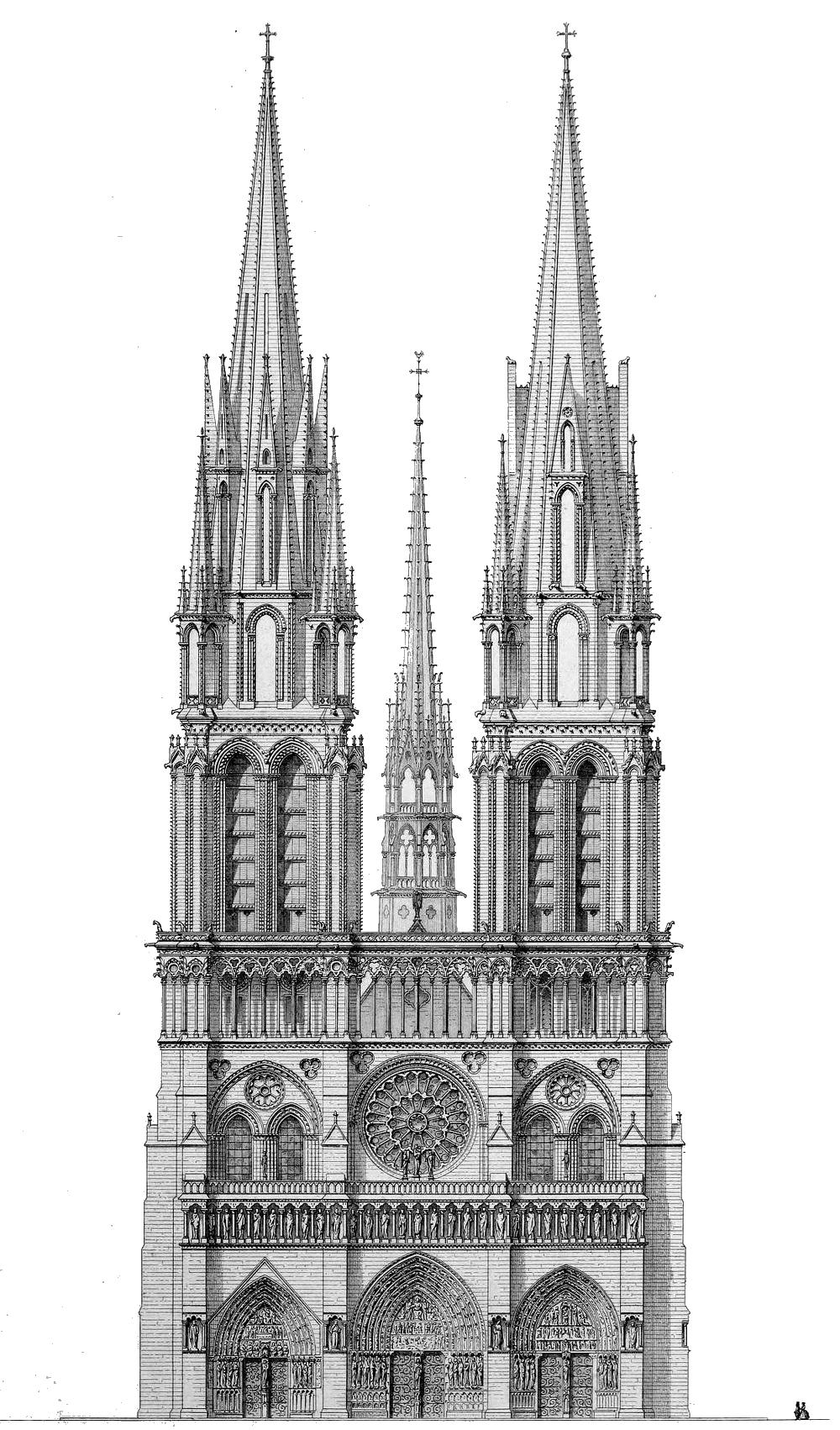

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Doom in Bloom

Such paintings were widespread in Catholic England where they served as a vital reminder to the faithful worshipping below of not just the torments of Hell but also the joys of Heaven. In the aftermath of the Protestant revolt, however, such vivid imagery was frowned upon, and the Salisbury Doom was painted over with limewash in 1593. Christ in Majesty was replaced by the royal arms of the usurper queen, Elizabeth I.

It was then forgotten about til its rediscovery in 1819 when hints of colour were discovered behind the royal arms. The limewash was removed, the remnants of the painting were revealed, recorded by a local artist, and then covered over yet again in white. Finally in 1881 the Doom was revealed to the world and subject to a Victorian attempt at restoration with mixed results.

Work on the church’s ceiling in the 1990s allowed experts to better examine the Doom which determined that, while there was a bit of fading, dirt was hanging loosely to the painting and it would be ripe for restoration. It has only been more recently, however, that money has been raised to restore the Doom.

There are other glories in this church yet to be restored, about which more information can be found on the parish’s website.

The Salisbury Doom before restoration (above) and after (below).

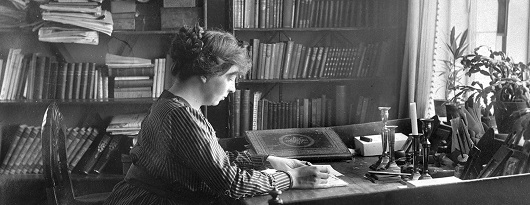

Understanding Undset

Sigrid Undset’s is doubtlessly among the twentieth century’s greatest writers, even though Kristin Lavransdatter, her main works of literature, is set in the fourteenth century. At the ceremony awarding Undset the 1928 Nobel Prize for Literature, Per Hallström described the writer’s narrative as “vigorous, sweeping, and at times heavy”:

It rolls on like a river, ceaselessly receiving new tributaries whose course the author also describes, at the risk of overtaxing the reader’s memory. […] And the vast river, whose course is difficult to embrace comprehensively, rolls its powerful waves which carry along the reader, plunged into a sort of torpor. But the roaring of its waters has the eternal freshness of nature. In the rapids and in the falls, the reader finds the enchantment which emanates from the power of the elements, as in the vast mirror of the lakes he notices a reflection of immensity, with the vision there of all possible greatness in human nature. Then, when the river reaches the sea, when Kristin Lavransdatter has fought to the end the battle of her life, no one complains of the length of the course which accumulated so overwhelming a depth and profundity in her destiny. In the poetry of all times, there are few scenes of comparable excellence.

Obviously Kristin Lavransdatter must be read for itself. I started reading it in the Stellenbosch University library a decade ago and was able to finish it thanks to being given a copy by a kindly Premonstratensian.

But the woman behind Kristin wrote more: her biographical essays and other works (like the one describing a visit to Glastonbury) are just as enjoyable and insightful.

At First Things, Elizabeth Scalia describes Undset’s lives of saints and holy men and women in Sigrid Undset’s Essays for Our Time.

Stephen Sparrow reveals much of Undset’s own biographical detail and how this influenced her writing in Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking.

But the best essay I’ve read on Sigrid Undset so far is David Warren’s meditation on womanhood, motherhood, and Kristin Lavransdatter. I don’t agree with everything he says (I rather enjoyed the new translation but am thinking I might have to give the old one a go), but David gets Kristin the character, gets Kristin the novel, and gets the way that life is refracted through both.

Read David Warren, then read Sigrid Undset.

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

The Feast of St Valentine in the Cape

Die fees van Sint Valentyn in die Kaap

A nice tradition!

’n Lekker tradisie!

Claudia McNeil

As a black Jewish Catholic, Claudia McNeil was pretty much everything the Ku Klux Klan hated. She was born to a black father and a part-Apache mother in Baltimore, Maryland but in her teenage years was adopted by a Jewish family in New York who instructed her in Judaism and taught her fluent Yiddish.

She married aged 19 but lost her husband in the Second World War and both her sons in the Korean War.

After training as a librarian, McNeil drifted into vaudeville theatre and nightclubs, eventually making her Broadway debut in 1953 as Tituba in The Crucible.

“The Jewish faith left an indelible stamp on her spirit,” Ebony magazine reported in 1960, “but she became a convert to Catholicism in 1952.” McNeil often reported that she stopped to pray before every evening’s performance.

Her most famous role was as the matriarch in A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, reprised in the 1961 film in both of which Sidney Poitier also starred.

Deeply appreciative of the gifts God gave her, McNeil was known never to turn down a chance to appear at charity benefit performances, especially for the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress.

Despite the losses she suffered in her life Claudia McNeil insisted “I have everything I’ve ever wanted from life.”

“I have more work than I can do. I have a nice, cheerful, comfortable home. I am solvent. Above all, I have strength, health, and peace of mind. I know where I’m going. I am an American citizen. I love my country. I pay my taxes and vote, and I intend to have a say in how my country is run.”

McNeil retired in 1983 and died ten years later.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Marian Chashuble

Now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, it was embroidered by the Sisters of Bethany, a Protestant order of nuns based in Clerkenwell. The Sisters specialised in church vestments and embroidery, and this object is believed to have been produced between 1909 and 1912.

Fr Anthony Symondson SJ has written in greater depth about Comper and the Sisters of Bethany here.

Rosary on the Coast

By all accounts last Sunday’s Rosary on the Coast was a resounding success. The initiative started out in Poland, where last year thousands of Catholics gathered at the nation’s borders and coastline to pray for the salvation of Poland and the world. Then a month later Ireland joined in with a Rosary on the Coast for Life and Faith, encircling the country in prayer.

Last Sunday, Great Britain got in on the action, and for three countries which have suffered centuries of Protestant domination it seems we have done rather well on these shores. Thousands of people from every variety of ethnicity, class, background, and experience gathered to pray the Rosary “for the spiritual wellbeing of our nations” (as the organisers put it).

The Rosary on the Coast was organised by lay people but supported by the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster as well as many other bishops and of course priests, many of whom accompanied and led in prayer the lay-organised groups around Britain. The rectors of the three national Marian shrines at Walsingham in England, Carfin in Scotland, and Cardigan in Wales all gave their backing and encouragement to the initiative.

Experience has taught me not to be surprised by the success of such ventures. I remember when the Cardinal renewed the consecration of England & Wales to the Immaculate Heart of Mary (with the visit of the Fatima visionaries’ relics). I didn’t have plans to go but friends were driving in from the West Country for it so I thought I’d meet up with them beforehand and go along.

We tried to get in but the doors of the cathedral were shut and a crowd waiting outside – it turned out the church was packed to the gills with the faithful. A pint later we tried again and they had just reopened the doors and let us in. Every bit of the mother church of the diocese was crammed with people, from Filipino maids to peers of the realm. Pews, aisles, side chapels – there was barely room to move. Priests were hearing confessions and the service was ongoing. We’re so used to being an embattled minority that sometimes we forget that we’re still the biggest show in town.

The good people at the Catholic Herald have collected a variety of photos from around the country, of which just a small sample are presented here. (more…)

Warwick Street Church

Over in Soho there is a curious little church with a fascinating history. The parish of Our Lady of the Assumption & St Gregory in Warwick Street started out as the house chapel for the Portuguese embassy in Golden Square, later occupied by the Bavarian embassy.

In recent years the Archdiocese of Westminster has placed the church in the care of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, and they have put new life into the strong musical tradition of the parish.

As chance would have, in my capacity as a professional web designer I was commissioned to design a new website for the parish.

You can view the new Warwick Street website here, and read a little more about its interesting history and architecture.

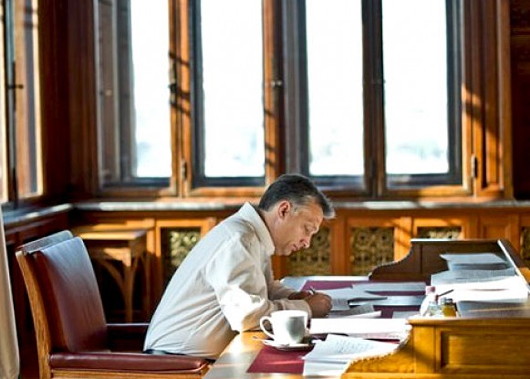

‘The right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so’

Welcome to Budapest. Today I do not wish to talk about the persecution of Christians in Europe. The persecution of Christians in Europe operates with sophisticated and refined methods of an intellectual nature. It is undoubtedly unfair, it is discriminatory, sometimes it is even painful; but although it has negative impacts, it is tolerable. It cannot be compared to the brutal physical persecution which our Christian brothers and sisters have to endure in Africa and the Middle East. Today I’d like to say a few words about this form of persecution of Christians. We have gathered here from all over the world in order to find responses to a crisis that for too long has been concealed. We have come from different countries, yet there’s something that links us – the leaders of Christian communities and Christian politicians. We call this the responsibility of the watchman. In the Book of Ezekiel we read that if a watchman sees the enemy approaching and does not sound the alarm, the Lord will hold that watchman accountable for the deaths of those killed as a result of his inaction.

Dear Guests,

A great many times over the course of our history we Hungarians have had to fight to remain Christian and Hungarian. For centuries we fought on our homeland’s southern borders, defending the whole of Christian Europe, while in the twentieth century we were the victims of the communist dictatorship’s persecution of Christians. Here, in this room, there are some people older than me who have experienced first-hand what it means to live as a devout Christian under a despotic regime. For us, therefore, it is today a cruel, absurd joke of fate for us to be once again living our lives as members of a community under siege. For wherever we may live around the world – whether we’re Roman Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox Christians or Copts – we are members of a common body, and of a single, diverse and large community. Our mission is to preserve and protect this community. This responsibility requires us, first of all, to liberate public discourse about the current state of affairs from the shackles of political correctness and human rights incantations which conflate everything with everything else. We are duty-bound to use straightforward language in describing the events that are taking place around us, and to identify the dangers that threaten us. The truth always begins with the statement of facts. Today it is a fact that Christianity is the world’s most persecuted religion. It is a fact that 215 million Christians in 108 countries around the world are suffering some form of persecution. It is a fact that four out of every five people oppressed due to their religion are Christians. It is a fact that in Iraq in 2015 a Christian was killed every five minutes because of their religious belief. It is a fact that we see little coverage of these events in the international press, and it is also a fact that one needs a magnifying glass to find political statements condemning the persecution of Christians. But the world’s attention needs to be drawn to the crimes that have been committed against Christians in recent years. The world should understand that in fact today’s persecutions of Christians foreshadow global processes. The world should understand that the forced expulsion of Christian communities and the tragedies of families and children living in some parts of the Middle East and Africa have a wider significance: in fact they threaten our European values. The world should understand that what is at stake today is nothing less than the future of the European way of life, and of our identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We must call the threats we’re facing by their proper names. The greatest danger we face today is the indifferent, apathetic silence of a Europe which denies its Christian roots. However unbelievable it may seem today, the fate of Christians in the Middle East should bring home to Europe that what is happening over there may also happen to us. Europe, however, is forcefully pursuing an immigration policy which results in letting extremists, dangerous extremists, into the territory of the European Union. A group of Europe’s intellectual and political leaders wishes to create a mixed society in Europe which, within just a few generations, will utterly transform the cultural and ethnic composition of our continent – and consequently its Christian identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We Hungarians are a Central European people; there aren’t many of us, and we do not have a great many relatives. Our influence, territory, population and army are similarly not significant. We know our place in the ranking of the world’s nations. We are a medium-sized European state, and there are countries much bigger than us which should, as a matter of course, bear a great deal more responsibility than we do. Now, however, we Hungarians are taking a proactive role. There are good reasons for this. I can see – and I know through having met them personally – how many well-intentioned truly Christian politicians there are in Europe. They are not strong enough, however: they work in coalition governments; they are at the mercy of media industries with attitudes very different from theirs; and they have insufficient political strength to act according to their convictions. While Hungary is only a medium-sized European state, it is in a different situation. This is a stable country: the political formation now in office won two-thirds majorities in two consecutive elections; the country has an economic support base which is not enormous, but is stable; and the public’s general attitude is robust. This means that we are in a position to speak up for persecuted Christians. In other words, in such a stable situation, there could be no excuse for Hungarians not taking action and not honouring the obligation rooted in their Christian faith. This is how fate and God have compelled Hungary to take the initiative, regardless of its size. We are proud that for more than a thousand years we have belonged to the great family of Christian peoples. This, too, imposes an obligation on us.

Dear Guests,

For us, Europe is a Christian continent, and this is how we want to keep it. Even though we may not be able to keep all of it Christian, at least we can do so for the segment that God has entrusted to the Hungarian people. Taking this as our starting-point, we have decided to do all we can to help our Christian brothers and sisters outside Europe who are forced to live under persecution. What is interesting about this decision is not the fact that we are seeking to help, but the way we are seeking to help. The solution we settled on has been to take the help we are providing directly to the churches of persecuted Christians. We are not using the channels established earlier, which seek to assist the persecuted as best they can within the framework of international aid. Our view is that the best way to help is to channel resources directly to the churches of persecuted communities. In our view this is how to produce the best results, this is how resources can be used to the full, and this is how there can be a guarantee that such resources are indeed channelled to those who need them. And as we are Christians, we help Christian churches and channel these resources to them. I could also say that we are doing the very opposite of what is customary in Europe today: we declare that trouble should not be brought here, but assistance must be taken to where it is needed.

Dear Friends,

Our approach is that the right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so. In this way we avoid doing good things simply in order to burnish our reputation: we avoid doing good things out of calculation, as good deeds must come from the heart, and for the glory of God. Yet now it is my duty to talk about the facts of good deeds. My justification, the reason I am telling you all this, is to prove to us all that politics in Europe is not necessarily helpless in the face of the persecution of Christians. The reason I am talking about some good deeds is that they may serve as an example for others, and may induce others to also perform good deeds. So please consider everything that I say now in this light. In 2016 we set up the Deputy State Secretariat for the Aid of Persecuted Christians, which – in cooperation with churches, non-governmental organisations, the UN, The Hague and the European Parliament – liaises with and provides help for persecuted Christian communities. We listen to local Christian leaders and to what they believe is most important, and then do what we have to. From them I have learnt that the most important thing we can do is provide assistance for them to return home to resettle in their native lands. We Hungarians want Syrian, Iraqi and Nigerian Christians to be able to return as soon as possible to the lands where their ancestors lived for hundreds of years. This is what we call Hungarian solidarity – or, using the words you see behind me: “Hungary helps”. This is why we decided to help rebuild their homes and churches; and thanks to Hungarian Interchurch Aid, in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon we also build community centres. We have launched a special scholarship programme for young people raised in Christian families suffering persecution, and I am pleased to welcome some of those young people here today. I am sure that after their studies in Hungary, when they return to their communities, they will be active, core members of those communities. And we are also working in cooperation with the Pázmány Péter Catholic University on the establishment of a Hungarian-founded university. The Hungarian government has provided aid of 580 million forints for the rebuilding of damaged homes in the Iraqi town of Tesqopa, as a result to which we hope that hundreds of Iraqi Christian families who now live as internal refugees may be able to return to their homes. We likewise support the activities of the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church. I should also mention something which perhaps does not sound particularly special to a foreigner, but, believe me, here in Hungary is unprecedented, and I can’t even remember the last time something like it happened: all parties in the Hungarian National Assembly united to support adoption of a resolution which condemns the persecution of Christians, supports the Government in providing help, condemns the activities of the organisation called Islamic State, and calls upon the International Criminal Court to launch proceedings in response to the persecution, oppression and murder of Christians.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

When we support the return of persecuted Christians to their homelands, the Hungarian people is fulfilling a mission. In addition to what the Esteemed Bishop has outlined, our Fundamental Law constitutionally declares that we Hungarians recognise the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood. And if we recognise this for ourselves, then we also recognise it for other nations; in other words, we want Christian communities returning to Syria, Iraq and Nigeria to become forces for the preservation of their own countries, just as for us Hungarians Christianity is a force for preservation. From here I also urge Europe’s politicians to cast aside politically correct modes of speech and cast aside human rights-induced caution. And I ask them and urge them to do everything within their power for persecuted Christians.

Soli Deo gloria!

F.C. Kolbe and the Tulbagh Drostdy

the Tulbagh Drostdy

Poet, Polemicist, Polymath, and Priest

Relic and emblem of a storied past.

Thrice happy they whose lines in thee are cast

Thy records summon all in thy embrace

To emulate the virtues of the race.

Thy stately halls of courtly manners tell,

Where only Ladies Bountiful should dwell.

Thy solid frame is pledge of future glory,

And links our doings with our country’s story.

Work on the Drostdy (magistrate’s house) at Tulbagh in the Western Cape began late in 1804 but progressed rather slowly and expensively. This is probably because — after construction commenced — the plans by Bletterman, the landdrost at Stellenbosch, were torn up by the architect Louis Michel Thibault and replaced by his own design.

This meant part of the work already completed had to be demolished and re-done, which Bletterman only went along with assuming Thibault’s plan had the approval of the Batavian Republic’s governor of the Cape, Jan Willem Janssens. As it happens, they did not, and when Bletterman found out he was none too pleased.

Francis Masey, a partner at Herbert Baker’s firm, noted that “[w]hilst it proved to be the last building begun upon Dutch soil in South Africa, it was destined to be the first completed upon the passing of the Cape into the hands of the British.”

This  brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

While his poetry was tended towards the middling, Kolbe was a distinctive polymath. In addition to catechetical writings, he published a number of works on Shakespeare, and lectured on Socrates not long after his 1882 return to the Cape. Eventually he was appointed Reader in Aesthetics at the University of Cape Town.

Kolbe also wrote a Catholic criticism of the 1926 book Holism and Evolution by the statesman General Smuts. (Not many people realise that the word ‘holistic’ was donated to the English language by a son of Stellenbosch.) The general and the priest had corresponded as early as 1915 when Smuts was Minister for Defence, and Smuts was so taken with Kolbe’s critique that he wrote a foreword to a later edition of it.

In a 1935 letter to “Dr. Kolbe”, the General wrote:

Although I am not acquainted with the Catholic prayers, I am deeply versed in the Psalms of the Old Testament, which seem to me the greatest and noblest outpourings of the human spirit ever put into language. The inexpressible finds expression there. Emotions almost too deep for utterance somehow find an outlet there. …

I also agree with you as to the nobility of the language which Catholic Christianity has evolved. What could match the beauty of De Imitatione Christi? Somehow it breathes a spirit which is beyond all language. It is curious how in such a case the human soul sets on fire its own earthly vesture, and language becomes a blaze of glory…

From Smuts’ letters to others we know that he actually read more works by Kolbe, in particular his Up the slopes of Mount Sion: or, A progress from Puritanism to Catholicism.

Disputation and discussion were also among Kolbe’s talents. He used the pages of South Africa’s Catholic Magazine to counter the accusations of what he called a “narrow clique” of anti-Romish ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church.

One of Kolbe’s most lasting legacies was the effect of his writing on the young Afrikaner philosopher Marthinus Versfeld (1909–1995) who converted to Catholicism under the late Monsignor’s influence. (Kolbe had died in 1936.) Versfeld’s familiarity with Augustine and Aquinas helped him launch intellectual attacks against the so-called “Christian-national” thinking behind apartheid, particularly in his first book Oor gode en afgode (“Of Gods and Idols”, 1948 & republished 2010).

Kolbe, according to Versfeld, “lived out a certain apprehension of the presence of the universal in the particular, just as Newman lived out his vision of the Catholic Church in the material of English circumstances.”

An Afrikaner Newman, perhaps? Worth reading more about.

First Gypsy Woman Martyr is Beatified

Emilia Fernández Rodríguez was killed during Spanish Civil War

The Catholic Church has beatified its first gypsy martyr in a ceremony in the Spanish city of Almería on the southern Mediterranean coast. Emilia Fernández Rodríguez, also known as “La canastera” (the basket-weaver), was one of 115 martyrs murdered in odium fidei by anti-Catholic militants during the Spanish Civil War.

The beatification ceremony took place in the city’s conference centre attended by over 5,000 people, including twenty-one bishops and four cardinals.

In 1938, Blessed Emilia Fernández was a poor gypsy woman living with her husband in Tíjola and surviving by basket weaving when the Republican forces occupied the town, shutting its church, and conscripting its menfolk. Emilia’s husband Juan with her help feigned blindness to escape conscription but was discovered and the couple were imprisoned separately.

Arriving at the women’s prison in Gachas-Colorás, Blessed Emilia was already pregnant and was jailed alongside many other practicing Catholic women who had refused to abjure their faith. Illiterate and never having been catechised despite being baptised, Blessed Emilia was taught how to pray the Rosary by another inmate. Her devotion to this Marian prayer and meditation attracted the ire of the prison authorities who threw her into solitary confinement for refusing to reveal which of her fellow inmates had catechised her.

After the birth of her baby girl, Ángeles, Blessed Emilia died as a result of her weakened condition from malnutrition and the appalling conditions of her isolation. Just twenty-three years old, her body was dumped into a common grave in Almería.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories