Baroque

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Courtyard of the Palazzo Bonagia

A photograph of the courtyard of the Palazzo Bonagia, the Palermo residence of the Dukes of Castel di Mirto, looking towards the rococo staircase.

The steps, columns, and balustrades are of red marble from Castellammare del Golfo, all conceived in the mind of Andrea Giganti, priest-architect of the Sicilian baroque.

The building was bombed during the last war and reduced to a shell, but thorough if slow-going restoration work began in 2009 and continues.

A Fifty Pound Note

The recent arrival of the new fiver has caused some flurry of excitement and one of the notes finally reached the Cusackian exchequer via the barmaid at the Ox Row Inn in Salisbury on Friday night. I’m indifferent to the design; it’s inoffensive but I’d prefer to see Churchill depicted in his coronation robes rather than Yousuf Karsh’s iconic photograph.

My favourite Bank of England note, however, remains the Series D £50 first issued in 1981 designed by the Black Country artist Harry Eccleston. Sir Christopher Wren lookings crackingly baroque, and St Paul’s Cathedral looms like a great ship over the City of London he helped to rebuild after the Great Fire 350 years ago.

Eccleston was the first banknote designer to work fulltime for the Bank of England which he joined in 1958, retiring in 1983, and introduced the concept of historical figures from British history gracing the back of the notes (which are of course fronted with an image of the Sovereign). This particular note was the first fifty-pound note to be issued since 1943. It was replaced in 1994 and withdrawn from circulation two years later.

The Spina di Borgo

The Baroque is a style of joy. It is often hailed (or derided) as the most Catholic of styles and in some sense this is true. The festivity and physicality of the Baroque reflect the God that Catholics worship — “the Love that moves the Sun and other stars” as Dante put it — but a Love made incarnate, made man, in a very real and tangible world.

The Baroque is also the style of the surprise: the corner turned to an unexpected vista or the jet of water sprinkling a king’s unsuspecting courtier.

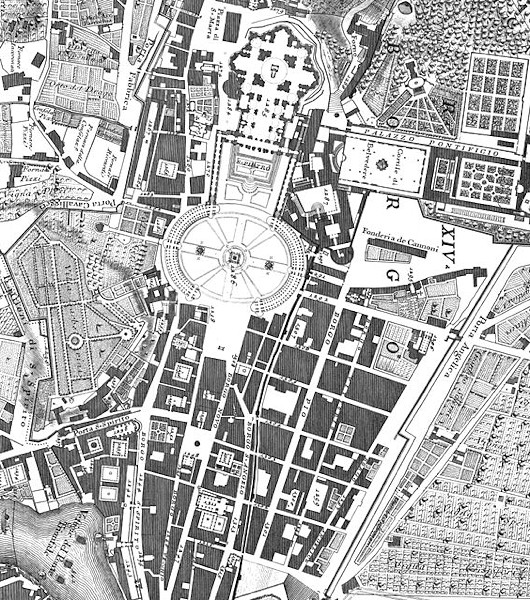

One of the most superb examples of this was the great basilica church of Saint Peter in Rome where prince, pilgrim, and pauper alike moved in a dark warren of palaces, hovels, churches, and alleyways, perhaps catching an occasional glimpse of the great dome looming as they closed in on San Pietro, finally to emerge from the shadow into the great light of the piazza.

That warren of buildings was the Spina di Borgo (“Spine of the Borgo”) but this experience is now sadly lost to us since the 1930s when the Kingdom of Italy’s fascist premier Benito Mussolini decided to raze the neighbourhood. Instead we now have the long boulevard called the Via della Conciliazione, named in commemoration of the Lateran Treaty establishing formal relations between the Holy See and the Italian state.

While Il Duce ostentatiously took credit for this urban crime by symbolically swinging the pickaxe beginning demolition, the concept, though flawed, was in fact an old one. Leon Battista Alberti submitted proposals during the reign of Pope Nicholas V (mid fifteenth century), and numerous other architects — Carlo Fontana, Giovanni Battista Nolli, Cosimo Morelli — drew up similar plans. The Piazza San Pietro only took its now instantly recognisable form in the 1650s when the curved flanking collonades enclosed the space like great welcoming arms superbly framing the basilica’s façade.

Mussolini turned to Marcello Piacentini — an accomplished if sometimes uneven architect — assisted by Attilio Spaccarelli. Piacentini favoured closing off the view from the avenue with a closed collonade, echoing Bernini’s own plans for the piazza, but was overruled.

The razing of the Spina presented a problem in that the undemolished buildings left flanking the Via della Conciliazione were now mostly at odd angles to the new boulevard. Piacentini attempted to solve this by flanking the road with two rows of obelisks that doubled as streetlamps providing a line directing the viewer towards the great basilica beyond, otherwise unimpeded by any visual interruption.

Overall the construction of the Via leaves a rather boring and clinical feeling. The charm and chaos of the Spina has been replaced by a clean and dull boulevard, useful for little more than traffic efficiency and crowd control. The loss of the Spina di Borgo is mourned.

A Baroque Church Portal

This church portal in the Oude Kerk of Amsterdam was originally in the Nieuwezijds Kapel, or Church of the Heilige Stede. That church was originally built in commemoration of the 1345 Miracle of Amsterdam, but after the ‘Alteration’ of 26 May 1578 — when Amsterdam’s Catholic city government was deposed and replaced by a Calvinist one — it and all the city’s other churches were taken over by the new Protestant administration.

In 1908 the elders of the Protestant congregation of the Nieuwezijds Kapel decided to demolish the fifteenth-century church and build a smaller one on the site, while building shops on the remainder of the site to prevent the resurgent Dutch Catholic church from building any chapel or shrine on it. This seventeenth-century baroque enclosed portal was then transferred to the Oude Kerk where it remains today.

Despite the anti-Catholicism of the Nieuwezijds Kapel elders in 1908, the Miracle of Amsterdam is still comemmorated every year on 15 March when thousands of pious Hollanders march in the evening Silent Procession (Stille Omgang). This year’s procession attracted 7,000 participants.

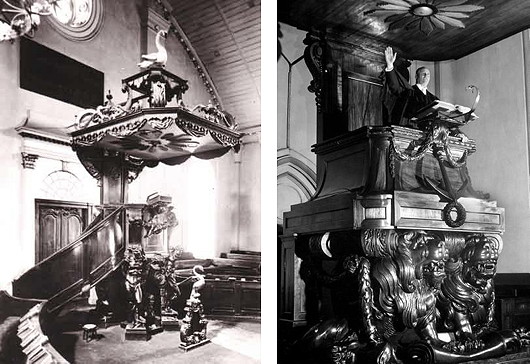

Interior of the Groote Kerk

1916; Oil on canvas, 29½ in. x 24½ in.

Though the painting is just a hundred years old, Gwelo Goodman depicted the scene as if in the late seventeenth century — when the Groote Kerk was first built.

While the body of the church was replaced in the 1840s, the elders of this most senior Nederduits Gereformeerde gemeente wisely kept the stunning baroque pulpit, the work of the Cape’s greatest sculptor Anton Anreith.

Shedding light on the Cape Baroque

Nuwe lig op die Kaapse barok deur Dr Hans Fransen

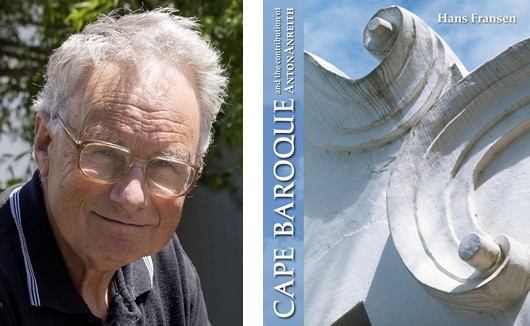

A NEW BOOK BY Dr Hans Fransen, the leading authority on Cape Dutch architecture, intends to shed new light on the Cape Baroque style through an examination of the work of the sculptor Anton Anreith. Cape Baroque and the contribution of Anton Anreith offers us the hefty subtitle of ‘A stylistic survey of architectural decoration and the applied arts at the Cape of Good Hope 1652-1800’, covering the period of the Dutch East India Company’s rule at the Cape.

The author investigates (says the publisher’s note) whether, and to what extent, the surprisingly rich body of Cape material culture can be seen as part and parcel of the international Baroque: that ebullient style of painting, architecture, and design that swept across Europe and some of its spheres of influence. After a highly interesting account of the origins of the Baroque in Italy and of its development in other parts of the world, the author concludes that ‘Cape Baroque’ does indeed form part of this. But he also points out that it has a very distinctive character of its own.

The book of 180 pages contains over 200 illustrations, mostly from the author himself, whose other works include The Old Towns and Villages of the Cape, The Old Buildings of the Cape, Drie Eeue Kuns in Suid-Afrika, and the introduction to A Cape Camera, the book illustrating the photography of early Cape photographer Arthur Elliott.

The sculptor Anreith, born in Germany at Riegel between the Rhine and the foothills of the Black Forest, was the finest and most florid artist of the Baroque in the Cape of Good Hope. His exceptional work on the pulpit of the Lutheran Church in Cape Town provoked the envy of the more prominent Dutch Reformed congregation, who quickly commissioned Anreith to carve an even more ornate pulpit for the Groote Kerk.

by Dr Hans Fransen, 160 pages, R250

deur Dr Hans Fransen, 160 bladsye, R250

The Lady Altar

The Oratory Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary,

Brompton Road, London

In the south transept of the Brompton Oratory is the altar dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, perhaps the finest altar in the entire church. It is a favourite place for getting in a few prayers and offering a candle or two or three or four. At the end of Solemn Vespers & Benediction on Sunday afternoon (above) it is where the Prayer for England is said and the Marian antiphon sung.

The Lady Altar was designed and built in 1693 by Francesco Corbarelli of Florence and his sons Domenico and Antonio and for nearly two centuries stood in the Chapel of the Rosary in the Church of St Dominic in Brescia. That church was demolished in 1883, and the London Congregation of the Oratory purchased the altar two years beforehand for £1,550.

The statue of Our Lady of Victories holding the Holy Child had previously stood in the old Oratory church in King William Street, and the central space of the reredos was slightly modified to house it. The Old and New Worlds are represented in the flanking statues, which are of St Pius V and St Rose of Lima — both by the Venetian late-baroque sculptor Orazio Marinali. The statues of St Dominic and St Catherine of Siena which now rest in niches facing the altar were previously united to it, and are by the Tyrolean Thomas Ruer.

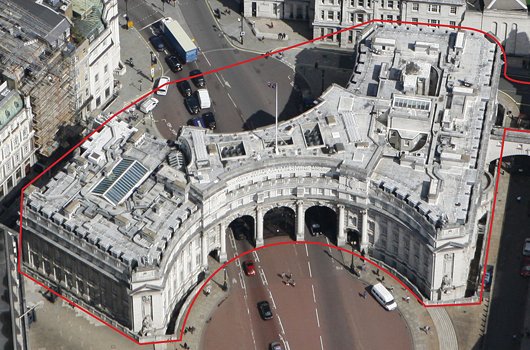

Admiralty Arch for Sale

Sort of: Queen Offers Long Leasehold of Edwardian London Landmark

SIR ASTON WEBB’S great Edwardian Baroque office-building-cum-triumphal-gateway, Admiralty Arch, will be offered up for a long leasehold by HM Government. The Grade-I listed building, constructed between 1910 and 1912, is one of the best-known in London for finishing the long view down the Mall from Buckingham Palace and connecting it to Trafalgar Square beyond. Admiralty Arch features 147,300 square feet across basement, lower ground, ground, and five upper floors.

Savills have been appointed as the sole exclusive agent to seek interest in the long leasehold. “The Government’s objective is to maximise the overall value to the Exchequer from the re-use of Admiralty Arch,” the Savills press release noted, “and to balance this with the need to respect and protect the heritage of the building, now and in the future, enable the potential for public access and ensure awareness of, and be prepared to respond to, potential security implications.”

Our prediction: oil money from abroad will turn it into a hotel. Boring, I know!

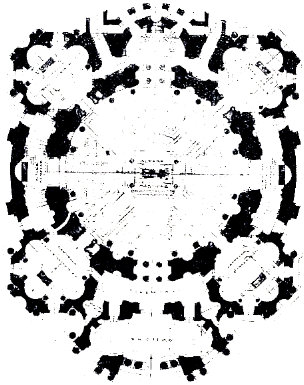

The Modern Baroque: Brasini in Parioli

The Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary

GOOD ARCHITECTURE requires a combination of willpower, taste, and resources. This nexus used to occur quite often; instances from the Renaissance and the long nineteenth century come most easily to mind. A late twilight of this combination is found in the magnum opus of the Italian architect Armando Brasini: the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Rome’s swish Parioli neighbourhood.

The  church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

Old Master Paintings at Sotheby’s

A Florentine Artist, The Madonna & Child Enthroned Flanked by Saints Bridget & Michael

1450; Tempera on panel, 72 in. x 85 in.

QUITE A FEW interesting pieces up for auction today as part of Old Master Week at Sotheby’s in New York. The above altarpiece has been attributed to various artists. For much of its life was called the Poggibonsi Triptych, but scholars now believe it to be the work of the Master of Pratovecchio. This attribution was supported by no less an authority than Roberto Longhi, who (as the catalogue notes point out) “considered him an artist of note who contributed to the Florentine transition from the early fifteenth-century serenity and intimacy of Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi to the more dynamic forms found later in the century.”

The altarpiece, commissioned from a certain Giovanni di Francesco in 1439, was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, which is now auctioning to raise funds for future acquisitions. (more…)

A Miscellany of Mexican Music

Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla was born in Malaga, Spain in 1590 but moved to New Spain in 1620, and was appointed choirmaster of Puebla Cathedral in 1628. His corpus is massive, with over 700 works surviving. His Stabat Mater is above, but you should also hear his Missa ego flos campi. (more…)

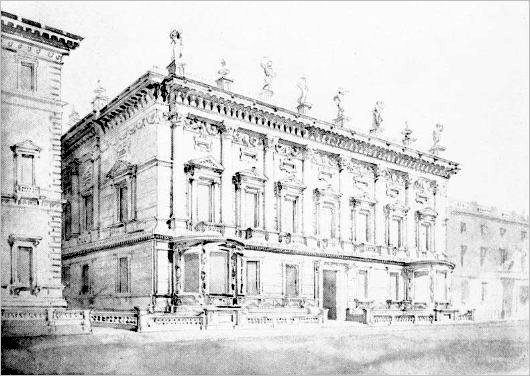

A Palace on Princes Street

The North British & Mercantile Insurance Company, No. 64 Princes Street

PRINCES STREET IS the thoroughfare of the nation, and its sad decline during the second half of the twentieth century and only partial comeback since then are reflective of Scotland itself. The architects of Edinburgh’s New Town had no idea that Princes Street would evolve into a commercial avenue, and the street was originally laid out as a handsome row of Georgian townhouses, built between 1765 and 1800, facing Princes Street Gardens and the Old Town above behind them.

Almost immediately the mercantile and social nature of the street began to assert itself, with shops and traders setting themselves up in the converted basements and ground floors of townhouses. The New Club showed up at No. 86 Princes Street in 1837, coming from previous premises in St. Andrew’s Square and before that Shakespeare Square (where the former G.P.O. now stands).

As the Victorian era progressed, more and more of the Georgian townhouses were demolished and replaced with new buildings in the varying styles of age. It was just two years after Victoria’s death that an old company built a new headquarters in a brimming Edwardian baroque: the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. (more…)

Cockerell’s Carlton Club

Charles Robert Cockerell is best known for designing both the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and its Cambridge equivalent, the Fitzwilliam Museum. He is also, alongside William Henry Playfair, responsible for the twelve-columned National Monument that sits atop Calton Hill in Edinburgh — allegedly unfinished, though there is considerable debate over whether this is so. It’s not widely known, however, that the famous architect Cockerell completed a design for a new home for the Carlton Club on Pall Mall in London.

Originally Cockerell had declined the opportunity to submit a design, with such lofty names as Pugin, Wyatt, Barry, and Decimus Burton also declining the offer. A few years later, Cockerell nonetheless worked on this design for the Tory gentlemen’s club, which is superior to that conceived by another architect which was eventually built. Cockerell devised a “lofty Corinthian colonnade of seven bays” according to the Survey of London. “The columns have plain shafts, their capitals are linked by a background frieze of rich festoons, and the Baroque bracketed entablature is surmounted by an open balustrade with solid dies supporting urns and gesticulating statues.” (more…)

Potsdam’s City Palace to be Resurrected

THE OLD STADTSCHLOSS of Potsdam, destroyed by aerial bombing during the Second World War, will rise again next to the Old Market in the Brandenburg capital. The provincial government has decided to rebuild the old Stadtschloss to serve as a home for the Landtag, Brandenburg’s provincial parliament. While it was first conceived of building a modern building on the site, or having some reconstructed façades and others modern, a €20-million donation from the software entrepreneur Hasso Plattner has ensured the façades and massing of the building will follow the outline of the old stadtschloss. The interiors will be simple and modern, and to keep the costs down, much of the finer Baroque detailing of the façades will not be included. “I hope,” Herr Plattner said, “that the necessary compromises do not diminish the great impression overall.” (more…)

Hans Laagland

Oil on wood, 1980

“It does not matter what the artist paints, but how he paints it,” proclaims the painter Hans Laagland. “That is why Rubens is a genius while Picasso’s work is passable.” Laagland, a Fleming himself, is one of the scant few artists in our day who paint in the grand style of the Flemish baroque master. He was born in Belgium’s Dutch province in 1965 and took up the brush and easel when ten years old. The young boy quickly developed a fascination with Rubens, considering and absorbing his works in the neighbouring city of Antwerp. Laagland’s emphasis is on traditional craftsmanship, painting in oils on wood panel, investigating and recreating the Old-Dutch lead white used by Rembrandt and the vermilion of Rubens. With a particularly capable hand at portraits, his work can be seen everywhere from the Norbertine abbey at Postel to the Belgian parliament in Brussels.

“It has been downhill ever since Rubens,” the painter says. Rembrandt — “Rubens’s disabled cousin” according to Laagland — was the last great painter; “What comes after him no longer has any significance.” Those versed in the Netherlandic tongue can read Mr. Laagland expounding upon his artistic ideas in De Kunstverduistering (“The Eclipse of Art”), his extended essay on art and painting now published as a book by KEI Zutphen. (more…)

Praga Caput Regni

Prague: Capital & Head of the Bohemian Realm

Prague is traditionally known as “Praga Caput Regni” — the capital of the realm, or indeed the head of the Bohemian body. Changing times and a different form of government mean that the arms of this ancient city now bear the motto “Praga Caput Rei Publicae” instead. The photographer Libor Sváček was born in the be-castled city of Krummau, and has a splendid book of photographs of that town, but here are a number of his photographs of Prague, which splendidly exhibit the Old Town at its most beautiful. (more…)

Krummau, Crown of the Moldau

BY NOW THE denizens of this little corner of the web are surely aware of Krummau, the splendid castle and town that towers above the banks of the Moldau river in Bohemia. I was never particularly interested in Bohemia until Fr. Emerson came up to St Andrews and gave a talk on the Hapsburgs. Unfortunately, this was before they began to record the talks (and offer them online) as it was an excellent brief lecture that I’d love to revisit. Now Bohemia is one of my passions, in addition to an increasingly large burden of passions (Scotland, New York, Argentina, the Netherlands, South Africa, France, Hungary, Transylvania, Canada, Scandinavia, … ). The architecture is superb and varied, and of course the Duke of Krummau is none other than a certain Prague pol. The complex is no longer in the Schwarzenberg family, but is instead now the State Castle of Český Krumlov.

The Chapel of Saint George in the Castle once contained the skull and bones of Pope St. Callixtus I. The remains were obtained by the Emperor Charles IV, who gave them to the Rosenberg family who built the castle, from whom they (and the castle itself) passed to the Schwarzenbergs, only to be lost after 1614. Nonetheless, the skull of an unknown North African martyr came here in 1663, and tradition donated to the unknown saint the name of Callixtus also.

Wisconsin Baroque, Priests, and Paper Architecture

Matthew G. Alderman

Taken from: Dappled Things, Ss. Peter & Paul, 2009

MY FAVORITE BUILDINGS never got around to being built. Some, like Sir Edwin Lutyen’s majestic design for Liverpool Cathedral, fell victim to budget cuts and the vagaries of history. Others were consigned by good taste, or occasionally outright timidity, to competition honorable mentions, and still others, like numerous student proposals or visionary dreams—like Boulée’s alarming hemispherical cenotaph for Newton, or an imaginary papal palace in Jerusalem cooked up by one of the votaries of the Vienna Sezession—weren’t terribly serious to begin with, unfortunately.

Note that I say favorite buildings, my own personal favorites, rather than the best or the most beautiful. Lutyens’ and Boulée’s fantasies may cross into that sublime territory of beauty by the power of their imaginative vision, but so many of the others owe their charm to their dreamlike extravagances, their intriguing if perhaps incomplete answers. An architect’s education lies in gathering up such fragmentary answers for the questions he will face down the road from clients and patrons. And therein lies the lure, and the value, of paper architecture.

I, like most of my colleagues, spent much of my time in school devising such useful fantasies, sometimes grand, sometimes small. Yet, they were not castles in the air. Each, while often existing in something like the best of all possible worlds in terms of budget and client, was grounded by an actual site and the laws of nature.

The most elaborate of all was my thesis project. It was an imaginary American seminary for a very real religious order, the fast-growing Institute of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest. This new congregation, dedicated to evangelization through the beauty of art, music, and the traditional Latin Mass, started out in, of all places, Gabon in Africa, but its present headquarters lies in Tuscany, in a villa bursting at the seams with seminarians in formation. While their ranks are dominated by Germans and Frenchmen, the increasing number of American clergy and their recent erection of a number of apostolates scattered across the Midwest suggested that a seminary in the United States, if not planned, might at least make for a plausible student project. Also, they seemed to have adventurous taste. I have since developed a passion for the Gothic but my first love has always been the Italian baroque. Perhaps they might be open to its vigorous beauty.

I garnered an award for the end result, the Rambusch Prize for Religious Architecture, and my putative patrons wanted copies of my enormous presentation watercolors to hang on their office walls—though, of course, the seminary would forever remain unbuilt. Its gigantic scale—typical for a student project—put it outside budgetary reach, unless, as someone cheerfully quipped, Bill Gates converted. Yet, the design was logical, consistent, and helped hone design skills I use every day at my drafting board.

The notion for the seminary came shortly after my first real-life encounter with the Institute’s work. My friends and I were road-tripping through the hill country of central Wisconsin, thick with vivid fall colors, and had just come back from a serene, silent low Mass and a long, talkative, private tour of St. Mary’s Oratory in Wausau. The Institute had transformed from a bland Midwestern Gothic to a dazzling near-replica of a fourteenth-century Bavarian court chapel. Bill Gates or no, these priests think big. Since then, they’ve overhauled a historic church in downtown Kansas City, and they’re presently turning their American priory from a burnt-out shell in a borderline south-side Chicago neighborhood into something out of Counter-Reformation Rome, and I have no doubt they’re going to succeed. Lest these projects seem like archaeological transplants, they are in fact derived from a logical extrapolation from local Catholic culture—Chicago’s colorful Polish cathedrals brought back to their ultramontane source, or, as I had just discovered, Midwestern Gothic returned to its Germanic roots. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories