About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us

“It was a little after nine in the evening; the sun was setting, the weather superb. … Nothing is rare, nothing is more enchanting than a beautiful summer evening in St Petersburg. Whether the length of the winter and the rarity of these nights, which gives them a particular charm, renders them more desirable, or whether they really are so, as I believe, they are softer and calmer than evenings in more pleasant climates.”

The Soirées Saint-Petersbourg of Joseph de Maistre are philosophical dialogues that sometimes border on the mystical and delve into the dark recesses of human nature. They are eloquent, fascinating, and beautiful, traversing a broad range of subjects while hovering around evil and why it exists in the world.

In this extract from the Fourth Dialogue, the Count — generally taken to represent the author’s own view — objects to the young Chevalier citing Voltaire approvingly.

A critic might call it a rant; if so, it is at least a beautiful one:

[…]The Count: Ah! I have got you there, my dear Chevalier, you are citing Voltaire. I am not so severe as to deprive you of the pleasure of recalling in passing some happy lines fallen from that sparkling pen, but you cite him as an authority, and that is not permissible in my house.

The Chevalier: Oh! My dear friend, you are much too rancorous towards François-Marie Arouet; since he is no longer alive, how can you keep up so much rancour towards the dead?

The Count: However his works are not dead. They are alive, and they are killing us. It seems to me that my hate is sufficiently justified.

The Chevalier: Perhaps, but permit me to tell you that we should not allow this sentiment, although well founded in principle, to make us unjust towards such a wonderful genius and to close our eyes to this universal talent, which must be regarded as a brillant French possession.

The Count: As great a genius as you wish, Chevalier, but it is no less true that in praising Voltaire, one must praise him with a certain restraint, I almust said grudgingly. The uncontrolled admiration with which too many people surround him is an infallible sign of a corrupt soul. Let us not be under any illusion: if someone, in looking over his library, feels himself attracted to the works of Ferney, God does not love him. Ecclesiastical authority is often mocked for having condemned books in odium auctoris; in truth, nothing is more just. Refuse to honour the genius who has abused his gifts. If this law were severely observed, we would soon see poisonous books disappear.

Since it is not up to us to promulgate such a law, let us at least be careful not to allow ourselves the excess, much more reprehensible than one might have thought, of exalting guilty authors beyond measure, and especially this one. He pronounced a terrible sentence upon himself, without noticing it, for he is the one who said: A corrupt mind is never sublime. Nothing is more true, and this is why Voltaire, with his hundred volumes, was never anything more than pretty. I except tragedy, where the nature of the work forced him to express noble feelings alien to his character, and even in this genre, which was his greatest, he does not deceive experienced eyes. In his best pieces he resembles his great rivals as the most able hypocrite resembles a saint.

However I should not be understood as contesting his dramatic merit. I restrict myself to my first observation, which is that when Voltaire is speaking in his own name, he is only pretty. Nothing can excite him, not even the battle of Fontenoy. They say, He is charming; I say it too, but I take this as a criticism. Moreover I cannot stand the exaggeration that calls him universal. I certainly see fine exceptions to this universality. He is nothing in the ode — and why should we be astonished by this? Considered impiety killed in him the divine flame of enthusiasm. He was also nothing — to the point of ridiculue — in lyric drama, his ear being absolutely deaf to harmonic beauties, just as his eyes were closed to those of art. In the genres that appear more analogous to his natural talent, he got along: so he was mediocre, cold, often heavy and gross in comedy (who would believe it), for the wicked are never funny.

For the same reason, he never knew how to write an epigram; the least vomiting of his bile required at least a hundred verss. If he tried satire, he slipped into libel; he was insupportable in history, despite his art, his elegance, and the graces of his style. No quality can replace those he lacked and which are the life of history — seriousness, good faith, and dignity. As for his epic poem, I have no right to talk about it, for to judge a book one must have read it, and to read it one must stay awake.

A stupefying monotony weighs on most of his writings, which were on only two subjects, the Bible and his enemies. He blasphemed or he insulted. His highly vaunted humour was however far from being irreproachable; the laugh that he excites is not legitimate — it is a grimace.

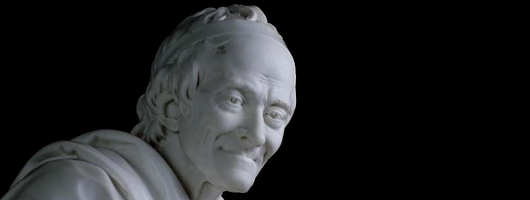

Have you ever noticed that the divine anathema was written on his face? After so many years there is still time to have the experience. Go contemplate his figure in the Hermitage Palace. I never look at it without congratulating myself that it was not done for us by some chisel imitative of the Greeks, which would perhaps have known how to render a certain idealised image. Here everything is natural. There is as much truth in this head as if it had been taken from a cadaver and placed on a plate. Look at this abject brow that never blushed from modesty, these two extinct craters where lust and hate still seem to boil. This mouth — I say it badly perhaps, but it is not my fault — this horrible rictus running from ear to ear, and these lips pinched by cruel malice like a spring ready to spout forth blasphemy or sarcasm.

Do not speak to me of this man; I cannot stand the idea. Ah! The harm he has done us. Like an insect, the scourge of gardens, who only attacks the roots of the most valuable plants, Voltaire, with his sting, never ceased to attack the two roots of society, women and young people. He injected them with his poisons, which he thus transmits from one generation to the other. It is in vain that to cloak his inexpressible offence, his stupid admirers bore us with sonorous tirades where he spoke superlatively of the most venerated things. These willingly blind people do not see that they thus accomplish the condemnation of this guilty writer. If Fénelon, with the same pen that painted the joys of Elysium had written the book The Prince, he would have been a thousand times more guilty than Machiavelli.

Voltaire’s great crime was the abuse of talent and the considered prostitution of a genius created to celebrate God and virtue. He could not, like so many others, claim youth, rashness, the heat of passion, or, finally, the sad weakness of our nature. Nothing absolves him. His corruption is of a kind that belonged only to him; it was rooted in the deepest fibres of his heart and fortified with all the strength of this intelligence. Always allied to sacrilege, it braved God while losing men.

With a fury that is without example, this insolent blasphemer went so far as to declare himself the personal enemy of the Saviour of mankind. He dared, from the depths of nothingness, to give him a ridiculous name, and this adorable law that the Man-God brought down to earth, he called INFAMOUS.

Abandoned by God, who punished him by withdrawing from him, he lacked all restraint. Other cynics astonished virtue, Voltaire astonished vice. He plunged into the mire; if he rolled in it, it was to slake his thirst. He surrendered his imagination to the enthusiasm of hell, which lent him all its forces to lead him to the limits of evil. He invented prodigies, monsters that make us blanch. Paris crowned him; Sodom would have banished him.

Shameless profaner of the universal language and its greatest names, the last of men after those who love him! How can I tell you how he makes me feel? When I see what he could have done and what he did, his inimitable talents inspire in me no more than a kind of nameless holy rage. Suspended between admiration and horror, sometimes I would like to raise a statue to him — by the hand of the executioner.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories