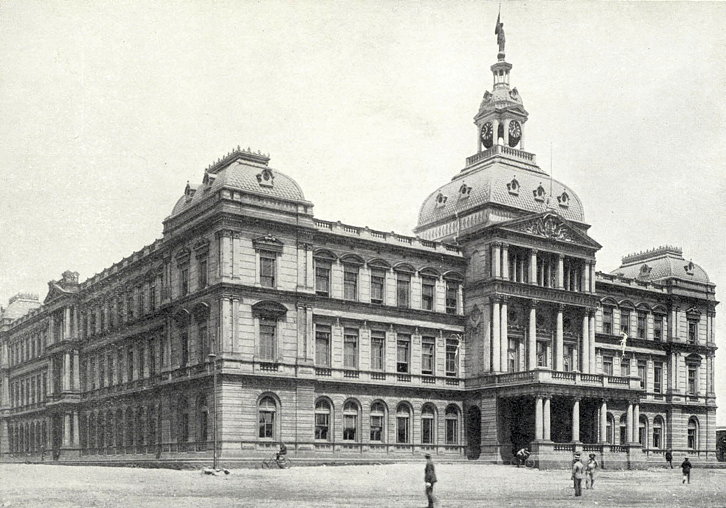

Kerkplein, Pretoria

Gauteng, the province which forms the highly urbanised heart of the old Transvaal, is not my area of specialty in South Africa, enamoured as I am of the Western Cape. Johannesburg, for all its financial prowess, is one of those towns that went from a collection of tents to a major city almost overnight with the Witwatersrand gold boom.

Pretoria, on the other hand — Pretoria Philadelphia to give its original name — exudes a more detached respectability perhaps enlivened by the ceremony of its century-long status as the executive capital of a unified South Africa. And sitting at the heart of the city of jacarandas is Kerkplein — Church Square.

Among the fine buildings on Kerkplein is the Ou Raadsaal, or Old Council Hall. The legendary president of the Transvaal republic, Paul Kruger, imported from the Netherlands a man named Sytze Wierda to hold office as State Architect & Engineer of the ZAR (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, as the Transvaal government was known). Kruger knew the capital city of Pretoria needed more handsome buildings to reflect the wealth of the upstart Boer republic.

The Raadsaal was built to house the Volksraad, the republican parliament, with the cornerstone laid by Oom Paul himself on 6 May 1889 and work finishing in December 1891. It was originally meant to be two main storeys, but the constitutional reforms of 1890 required an additional storey to be added mid-project. Portraits of President Kruger, Commandant-General Joubert, and other ZAR leaders still look down on the seats in the plenary chamber.

While the building, restored in the early 1990s, is owned by the municipal authorities in Pretoria, I’ve no idea what the building has been used for in the intervening decades. I believe it was used by the Transvaal Provincial Council from the establishment of the Union of South Africa until the four provinces were broken up into nine, but online sources are not clear.

Nearby the Ou Raadsaal is the former Nederlandsche Bank designed in a florid Dutch Renaissance style by Amsterdam-born and -trained Willem de Zwaan. Nedbank is now one of the “Big Four” commercial banks in South Africa but it was founded in Amsterdam in 1888 as the Nederlandsche Bank en Credietvereeniging voor Zuid-Afrika (Dutch Bank and Credit Union for South Africa / Nederlandse Bank en Kredietvereniging vir Suid-Afrika), to provide Dutch finance for the rich pickings in the Witwatersrand.

The building was built in 1896 and Nedbank only moved out to more spacious quarters nearby in 1953. This handsome Dutch transplant is now the Pretoria tourist information bureau.

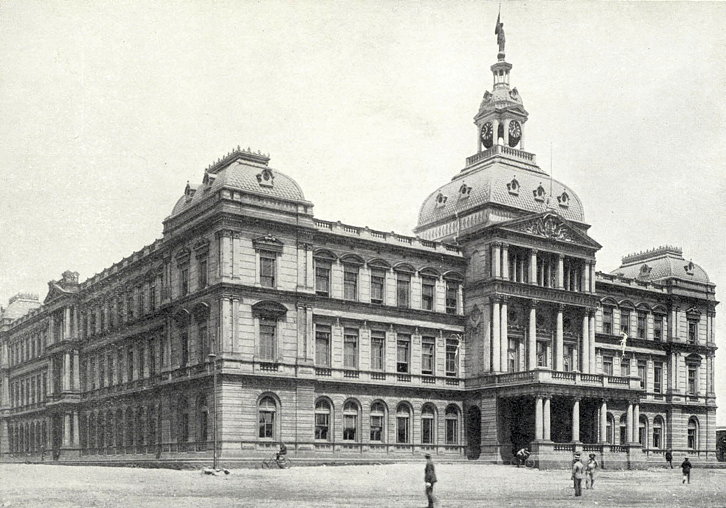

The other great building on Kerkplein is the Paleis van Justisie (Palace of Justice), also by Sytze Wierda, and directly across the square from the Ou Raadsaal. Work began in 1897 but was not completed until after the Anglo-Boer War. As home to the Transvaal division of the Supreme Court of South Africa the building was home to the 1956 Treason Trial and the Rivonia trial of 1963-64, in which Nelson Mandela was convicted of offences against the state and subsequently imprisoned.

The interior of the Paleis features three luxuriously spacious lightwells (see

here and

here) where courtgoers could meander while awaiting the course of justice. The building now houses the Gauteng Division of the High Court of South Africa.

But wait a minute: it’s called Kerkplein, Church Square, but where’s the church? The Dutch Reformed Church was first built on the square in 1854, a simple country church with stepped gable and a thatched roof. This burnt down in 1882 and was replaced with a neo-gothic structure designed by the partnership of Claridge & Simmonds and built by Charles Clarke (“One of my tame Englishmen” President Kruger said of Clarke). The work was faulty, however, and within a quarter-century the building was declared structurally unsound and demolished. I believe the nearby Groote Kerk was built as a replacement, leaving the square free of buildings and dominated by

Anton van Wouw’s sculpture of Oom Paul.

The scenes Kerkplein has witnessed over the years have been varied: the first raising of

Vierkleur, the election of Oom Paul as President, the raising of the Union Jack after the fall of Pretoria during the Anglo-Boer war, and the Proclamation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, amongst others. One of the most significant was (

above) the Proclamation of the Republic of South Africa in 1961 and written about previously

here, marking as was thought at the time the final triumph of

Boer over

Brit. Later years saw protests by anti-apartheid activists and radical white nationalists, but under the “new dispensation” most of this has faded into the background as Kerkplein has resumed its role as the town square for the Republic’s capital.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

You always pen such fascinating articles, Andrew. This one did not disappoint. Thanks.

Andrew, while searching the web for vintage photos of a heavy snowfall on Table mountain(right down to Tafelberg Rd),plus the top ofSignal Hill I came across your unique blog & what an erudite treasure trove of information,opinion elegantly stated it is proving to be. I would just like to thank you for your cultural contribution over a wide front.

Many thanks,

Sean-Michael Mc Cullagh

Kruger’s “mak Engelsman” (“tame Englishman”) was my great-grandfather, Charles Clark (without the “e” on the end of his surname). He also built the Krugerhuis (Kruger House), Paul Kruger’s modest residence on Church Street. The cement used to build it was of such a poor quality that it was mixed with milk rather than water. I have no idea whether this made it stronger, but the home, now a museum, still stands! Another family legend has it that when the building reached roof height, Charles hoisted the British Union flag on the beams. Kruger, understandably, was quite irate. When asked why he had done it, my great-grandfather said that as Kruger had yet to pay for it, the building was legally his, and as a British subject he was entitled to hoist the flag. Furthermore, he added, it was customary for the owner-to-be to pay for a round of drinks for the builders at that point of the construction. Kruger reluctantly parted with a pound, and enjoined Charles to make sure that “the coloureds (skilled builders employed by Charles)don’t get drunk”. Charles and his wife lived in Pretoria during the Boer War and when Pretoria was occupied by the British, the military authorities commandeered all his wagons and oxen. Outraged, Charles downed tools and never worked another day in his life. My grandfather was one of thirteen children Charles had. He fought in the First World War as one of the first South Africans in the fledgling Royal Flying Corps. One of his brothers was an MP in Smut’s government after WW2 and when Smuts lost his seat in the 1948 elections, turned it over to Smuts so he could remain in parliament as leader of the opposition. I was born in Pretoria and still have siblings living there.