About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

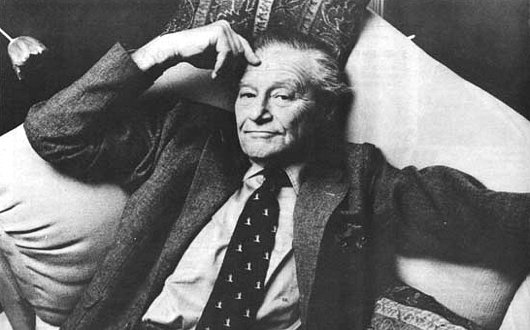

Gregor von Rezzori

THE BOOKS OF Gregor von Rezzori, according to the introduction to this interview (found via Three Percent), depict “a world now almost wholly disappeared—Central Europe in the years between the two world wars—through the memories, ruminations, and loves of their narrators, men who have survived into the postwar new Europe but who can never fully detach themselves from that lost world. It is Gregor von Rezzori’s world, too. An Austro-Italian nobleman born in the Bukovina region of Rumania in 1914, von Rezzori was raised there and in Vienna. He lived in Germany during and immediately after the Second World War, and he currently divides his time between Tuscany and New York.”

Bruce Wolmer I’m tempted to begin by asking the question interviewers on French TV like to pose: “Gregor von Rezzori, qui êtes-vous?”—Who are you? Which is immediately funny considering that the enigmas and paradoxes—and humor—of identity is a central concern of your work. But one wouldn’t know that reading the reviews, where you’re almost inevitably conflated with the first-person narrator.

Gregor von Rezzori Absolutely. This is such an old discussion: To what extent are books autobiographic? It’s ridiculous. As Flaubert famously said, Mme. Bovary c’est moi. You can’t eliminate yourself totally unless you’re Shakespeare.

BW That goes against the grain of much contemporary opinion and practice, which claims to be getting down to the truth of the author rather than the truth of the fiction.

GvR The Death of My Brother Abel is narrated by a writer. The narrator, the “I”—and funnily enough he is less my own person than any other first person in any of my other books—the narrator in The Death of My Brother Abel is a totally fictitious character. But, of course, nowadays people have little curiosity about examining such complexities. There is this desire of authenticity and transparency which connects with the curious contemporary belief that everybody is, or should be, an artist.

I must tell you that when I was young I never had the faintest idea that I should ever become a writer. I studied mining engineering, of all things. I came to writing by accident at a rather ripe age. I never thought of really having the urge to express myself, but obviously I had it in some way or other. But without ever having heard the phrase, I had to find my identity. That’s one of those dreadful verbal expressions. A phrase like that becomes fashionable and then becomes a slogan and becomes really a program for people’s lives. Every young man or girl nowadays ponders about his or her identity without even realizing what it is. My identity is “I”. It takes a long time to learn that that much celebrated “I” is never lost, but never really found either.

Anyway, in my case I was having a period in my life in which I didn’t have anything else to do—this was before the war—so one day I sat down and wrote a story. Somebody got hold of it and sent it to a publisher. They instantly wanted me to write another one, which I did. Because I thought, my God, this is a very agreeable way of earning money. How wrong I was I found out later. But by then it was too late.

BW A disagreeable way of not earning much money.

GvR Yes, yes. Somebody with a little bit more intelligence doing the same amount of work, you’ll become an Onassis. Well, who needs that? But it’s in real disproportion. Then when I realized what crap I had been writing, you see, I sat down, and just then the war came. I was fortunate—I didn’t actually have to be a soldier exactly. I was born in Bukovina, Rumania. Before Rumania went into the war it was given to the Russians so I was already more or less a Russian although I still had a Rumanian passport and was living in Vienna at that time. When Bohemia was taken by the Russians I went to our ambassador in Berlin, who was a friend of the family, and I said, “What shall I do, what am I supposed to do?” He said, “Well, you are supposed to go home and find a new identity because you don’t exist. And then you’ll die from Mr. Hitler because within a short time you shall have to join in those struggles. I can’t prolong your passport. How long is it still valid?” I said. “For a year.” He said, “Keep quiet.” Which I did. It lasted for three more years during the war. I had my share of bombing and all that, but in the meantime I had the opportunity to really fill the unbelievable gaps in my knowledge by reading. I must tell you that I read very slowly and I need months to finish a real masterpiece, for example one of Broch’s novels.

BW I too read very slowly, and The Death of My Brother Abel took me a couple of months, which was fine, but it was interesting to see in the reviews how impatient everybody is: “Well, yes, there are wonderful bits here, but we shouldn’t be required to sit and…”

GvR Yes, the chutzpah to offer you 600 pages!

BW If one were to race through it, though, to read for information, one would lose a sense of the sheer intensity of the language. There are sentences in The Death of My Brother Abel so beautiful that they quite literally stopped me for five or ten minutes.

GvR What makes for the beauty of Proust, say, is that each page is a picture in itself. But it seems that to get people to read a thick book you need to offer them a juicy subject. Look at Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. People are buying it, people are reading it like mad. For the so-called information, I suppose. A dreadful book.

BW When did you begin to think of yourself seriously as a writer?

GvR In Germany, right after the war, something absolutely absurd happened. You see, I sat down and for the first time I really wrote aggressively and got rid of all my hatred against a particular kind of German. I wrote a book—it wasn’t published until 1954—which the publisher rather ludicrously decided to call Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad —”Oedipus Triumphs at Stalingrad.” But while I was writing that I was also working for the British-controlled radio in Berlin. One day there was a gap in the program and they said, “You are always telling us your silly stories, Jewish jokes, and God knows what all, now go and tell them on the microphone.” Well, there’s nothing more unbearable than somebody who tells one joke after the other. So I combined them into an invented country, which I called Maghrebinia. To make a long story short, the broadcast became a roaring success and the stories from Maghrebinia came out before the novel. With the consequence that, you know how Germans are, from that moment on I was The Maghrebinian. Tell any cafè waiter in Berlin or Frankfurt that you are a friend of mine and you will be superbly served.

BW Tales from Maghrebinia were lighthearted, popular stories?

GvR Of course. It was a success mainly because it was the first book after the war that you could laugh at. And it was hilarious and rude and whatnot, sort of Rabelaisian. It was also the first book after the war in which, with all the collective guilt then being felt in Germany, you could read a Jewish joke. As I say, it became a great success. I never got rid of that, whatever I wrote afterwards. It was read in the wrong key, so to say; people were always expecting me to be satirical and to make jokes.

BW Why wasn’t Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad ever translated into English?

GvR It can’t really be translated, because it’s written in sort of German slang as if Ernst Junger were a drunken Prussian officer telling a story in a bar. It’s about German snobbism, about somebody who comes to Berlin in ‘38 in order to conquer the world, a sort of Berlin Rastignac. It pokes fun in a most atrocious way. The next book I wrote after this was a long novel, which has been translated into English as The Hussar. And then came An Idiot’s Guide Through German Society, which also began as a series on the radio. This offended many people because I had my finger in a burning wound. I claimed that in spite of everything that had happened since 1918 in Germany, the social structure had not altered, you still had an aristocracy with enormous prestige and wealth. And I poked fun at all that. But I’m not at all interested in what happens in Germany any longer. My books don’t sell there and my work is not taken seriously.

BW Abel took a very long time to write, yes?

GvR Indeed. More than 15 years. I disappeared for a while, so to say.

BW During that 15 year period while you were working on Abel you went to Italy?

GvR Yes, I was already in Italy. I am in Italy 35 years now.

BW The Death of My Brother Abel is an extremely ambitious book. There are very few contemporary books that have such a level of ambition—in literary terms, intellectually, historically, and even spiritually.

GvR Lady Annan called her piece about it in The New York Review of Books, “Transcendental Chutzpah.” Well I mean, see, it’s a book for writers. It’s not a book for readers. I like to joke that it should be read in creative writing classes. It is not for the normal reader. It took me 15 years to do and was my own attempt to understand what I was doing as a writer.

BW One of the issues explored in The Death of My Brother Abel is the death of Europe. Europe as a culture, as a way of life. That death has been, at least partially, to the benefit of America. You have that extraordinary, almost hallucinatory, passage in which your character Jacob G. Brodny, born in Central Europe but now a fabulously successful American literary agent and wheeler-dealer, is seen to wolf down the masterworks of European culture as if they were patè.

GvR My aggressiveness is not directed against America and Americans, it’s against Americanism, which is mainly a European phenomenon. Brodny is not genuinely an American. He’s an immigrant who came over here. He behaves more American than any other American, which you can see. And personally, if you ask me, I love and admire America. European culture has not been killed by America. It perhaps committed suicide during the First World War. And this is a thing which I also want very much to emphasize in the next volume of mine, which will be called Cain.

BW The idea of a culture committing suicide is right beneath the surface of Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, as well. Reading it, one becomes aware that the killing of the Jews in Europe, the Holocaust, was not only murder, but the suicide of a world, because for all the antagonism and dislike between the aristocratic and the Jewish characters, they existed in some necessary relationship, some vexed sympathy. They both shared a world that has now vanished. Perhaps it was just that that world vanished, but Jews lost something rich and irreplaceable as well. The moral difference being, of course, that nobody gave the Jews a choice in the matter.

GvR You see, first of all, I do believe that the aristocracy as a class never hated the Jews. On the contrary, the Jews were an object of jokes or disdain, in fact, but many other groups were much more so. As for the peasants and the Jews, it’s a somewhat different story. Whatever a peasant produces is by his hands and due to rot away. He slaughters the pig, but he can’t keep it for any more than a week or so. The Jews, on the contrary, had something that increased its value with time: money. That’s why it was easy for the peasants to believe that the Jews were the evil, exploiting ones.

BW Elie Wiesel has described Abel as an elegy, “the story of Europe seen through the eyes of despair.” How would you describe what has been lost from that world?

GvR Ah ha! Let me answer this exactly. What’s been lost is a particular light, a particular quality of air. And pity—the loss of pity is perhaps our greatest loss.

Now we have a completely different feeling for time, for instance. Time itself has changed. This is due to a blind belief in science. The simple fact is that European life nowadays, just like American life, is determined by money, led by money, as let us say a European would have been led by religion in the 14th century. In every aspect of life, money shows the way. It’s not that this loss happened from one day to the next; as a matter of fact, it’s a loss that started with the French Revolution, at least. Well, all this is rather vague. I shall have to find more metaphors for it.

BW Saying this flies right in the face of the optimistic consensus pervading modernity, the belief that most historical change, most technical and social innovations have been, on balance, for the better. You, or at least the narrators of your books, seem on the contrary to regret them.

GvR You see, I’m profoundly distressed, call it skeptical, and I don’t think I’m alone in becoming aware that we’re in a rotten place. We’re a rotten people; our culture is rotten. Deeply rotten. And to me the proof is that whenever we come in contact with another people, they are destroyed. A friend of mine who’s really one of the last really honest dealers in African art told me that he came to tribes which had never before seen a white man. The simple fact is that they look at him, and that he has a knife or lighter or something—it’s already a deadly encounter. You see, it’s lethal for them already. Similarly, I recently came back from China. The Chinese of my time were pig-tailed and Chinese, but nowadays they are exactly like myself, just a little bit more ethnic. It’s not really to their best interest. What I felt there now was that they have gotten rid of political fantasies and are fortunate enough to have had a religion, an early religion, sort of a black beaten-down art, so they can cope with such a loss in a rational way.

BW In your books there are passing references to the futility of revolution and of politics more generally. Were you affected, as were so many of your generation in Europe, by utopian hopes?

GvR Yes, of course, as a young man. Of course. I couldn’t very well escape from this. In the atmosphere of the ‘30s we all believed, even without an articulate ideology. We all believed in a new world that was about to come. The promised technology. Utopia. Look at the paintings of Kupka at that time. You saw Metropolis everywhere. And Metropolis is not thinkable unless a new man and a new woman are created, a new mankind. In the ‘20s and ‘30s we were unbelievable optimists, you see, who were then bitterly disappointed. But my skepticism, my pessimism, is not just the result of political failure. It goes much deeper. Much deeper. And I haven’t found an answer. I mean whenever I think of it, of what’s been lost, it certainly hasn’t been lost by the Americanization of Europe. What I call Americanization would have happened even without America. The greed for money, the power of technocracy and misunderstood science and so on, all that would have happened even without the example of America. What has been lost is pity and the capacity to dream. You Americans still have the capacity to dream even if you are also sleepwalking in a merry way. But we can’t any longer. We’re awake. Too much awake. Europe is silent and exists now in an abstract way, totally according to abstract rules. For instance, when I say we’ve lost pity, you can see just one small example of it in, say, the demonstrations for the victims of Mr. Pinochet or whoever. But you wouldn’t find those vociferous protesters caring about the beggar on the street. That direct relationship between human beings is getting lost due to abstract ideas about humanity.

BW Ideology.

GvR Yes. Ideology. Political ideology.

BW Which, of course, is a major theme of The Death of My Brother Abel: the increasing abstraction of life, the emptying out of experience.

GvR Exactly.

BW Which leads to the question, Pilate’s question, your books pose so often: What is truth?

GvR What is reality?

BW What is reality and what is fiction and what are the transformations and negotiations between them? You plainly dislike the society of information, the society of media, where people think they’re getting reality from newspapers, television, and magazines. Instead, you’ve said that Anna Karenina — now there’s reality!

GvR Do you remember in Abel there is a long, long, perhaps much too long passage on the narrator’s having an affair with a girl who lives in one of those postwar high-rises. He visits her and thinks about the fictitious reality forced on us by the media and how you lose your identity because you don’t know who you are to cope with all these things which are much beyond your reach, beyond your personal sphere. I mean everything in our time is done, is given, to lose your identity. Then, of course, you have to go look for it, to put it primitively.

BW In terms of your own writing, how does that govern your aesthetic? Not to put too fine a point on it: Why do you write?

GvR Yes, yes, yes. Why do I write? “What sin to me unknown/Dipped in ink, my parents or my own?” Listen, I suppose that in fact writing, whether you know it or not, is the attempt to find an identity. Knowing the secret of the “I” that never can be lost in spite of all the changes it undergoes throughout a lifetime, there you have already the secret theme of every fiction writer, don’t you think so?

BW The search for the voice?

GvR The search for the voice. Also the search for the secret of transformation, of living many lives in one life. The possibility of what I do, of writing hypothetical autobiographies endlessly. And, I mean, Anna Karenina is a reality in so far as it is the most dense invention of fiction, the most concrete.

BW You frequently allude to Nabokov’s saying that when we speak of reality we must put it in question marks.

GvR In quotation marks. Which, of course, are also question marks here.

BW What has been Nabokov’s influence on you?

GvR Well, there were many other influences first. I didn’t read Nabokov until late. But when I had started to write Abel in its first version, I got Nabokov’s Pale Fire in my hand and instantly put my pen down because I found that there was the book I wanted to write already in the best possible form. Then I collaborated on the translation of Lolita into German, and I became aware that I shall never achieve the almost medieval craft of Nabokov’s to link fiction with literary allusion and write a book on many layers—of which one is a direct and fictitiously concrete reality, and behind there is the other reality, the literary reality of all the allusions, all the relations of literature with other literature. At the same time that it’s discouraging, it’s very challenging.

BW Other influences?

GvR Everything influences you as a writer, whatever you read. I believe there isn’t any such thing as a bad book, because you take out of any book something by which you learn, even if you throw it away. Then there are writers who encourage me immensely and writers whom I admire so much that I put down my pen and say, “I can’t write.” For instance, I can’t read ten lines of Robert Musil and keep on writing, I stop for a week at least. Even Joyce. He discourages me totally. But then there are others who encourage me. Thomas Mann with his sort of schoolboyish sense of humor challenges me to get a little subtler. Ironic. And so on.

BW Cèline?

GvR Well, yes. Not consciously, but the violence. In literature, particularly at that period, a certain barbarism is necessary. Also for the sake of honesty. You can’t be suave and God knows what in a time like ours. Also there is in him an urge for iconoclastic action which was also very much an aspect of German Expressionism after the First World War.

BW Your narrator says he seeks to write in “a style of barbaric haul gout.” There is anger and disgust beneath the suavity and jaunty, nonchalant elegance of your prose.

GvR I’ve become aware that I can only write well out of either love or hatred. Direct feeling. I need that. When I love it becomes, because I am sentimental to the core, it becomes too sweetish. It’s like playing on the cello. The best things are wrought in hatred. The more the world around myself gets nostalgic, the more furious I become with nostalgic feelings. I know there’s something I deeply mistrust in that. In fashion, in modes of living, people are trying to revive bits of history, the ‘20s and ‘30s particularly, that they don’t understand. Take the German painter Anselm Kiefer, who’s accused by some Germans of being nostalgic for Nazi times, which is absurd. But if he is, he’s doing the same thing as everybody else does. Without realizing that they are nostalgic for the ‘20s and ‘30s they are nostalgic for what formed fascism.

BW Kiefer’s watercolor Winter Landscape was used for the book jacket of The Death of My Brother Abel.

GvR Yes. Kiefer also denounces in sorrow and in anger. I like him very much.

BW In Abel, you talk about the relation between individual literary style and the zeitgeist, that it is not we who write, but the times which write us, so to speak, which demand a style of us.

GvR Whatever we do is not only led by our individual fullness but by trends in the zeitgeist, by things that are far out of the reach of our control. We don’t know what happens to us. I mean the simple proof is that if you take a German newspaper of, say, 1934 and read an article written by Dr. Goebbels, you wouldn’t believe your eyes. The crap he has said. And—I know, I lived through it—people read it as if it were the Bible. Intelligent people, but totally blinded at the time. Or, another example I use, people from a particular epoch all have a more or less similar handwriting. You can recognize it as 18th century, or whatever, at first sight. It means that something happens to us which we don’t even realize, in ideas as well as in our way of perceiving the world. For example, the break between Romanesque and Gothic art or, in our own time, the sudden break into abstract art, you can’t tell me that it’s a logical evolution. That is rationalizing it as historians always do—backwards.

BW You’re not saying, however, that individual style doesn’t exist?

GvR It certainly exists. There are artists who are not great in the sense of a new creation but just because they represent in the utmost possible form the style of their period. Somebody like Seurat, for instance, is not a great genius in painting, but still such artists represent their period and the spirit of their period in the purest form. But nothing more, nothing personal.

BW Which would make them inferior to an artist who’s able to…

GvR Picasso certainly is not in that line. He’s overwhelmingly personal and individual. Those others aren’t.

BW And in terms of your own work, you would aspire to…

GvR Oh my God! It sounds silly, but I am so astonished that I can write a phrase at all that I wouldn’t know, I don’t reflect that much. I don’t put myself in any rank or school or anything of that kind. I believe that I’m rather personal, but as for representing a particular zeitgeist…I may. I’d be very proud if I did. On the other hand, I have written in Abel many times that the tremendous fear of any writer or artist who believes that he has some idea, something to say, is that they know perfectly well that at the same time, the very same time, hundreds of others have already either said it or are about to say it or there’s another chap who says it much better and liquidates you totally.

BW You have been widely criticized for having your narrator in Abel say that the postwar Nuremberg trials were a sham. As you yourself covered the trials for the Hamburg radio, I assume that you feel similarly.

GvR Let us put that straight. First of all. I do not believe that the Nuremberg trials were a complete sham. They were a failure and therefore a great delusion. This was not due to, say, moral failing or any manipulations behind the scenes, it was due to my great enemy, stupidity, overwhelming collective stupidity. Or the impossibility, even on the part of intelligent people, to cope with things established by stupidity. For instance, you know there has been endless discussion about the legal basis of the trials. And I hope that I have the opportunity to expand this a little bit more explicitly in Cain, the book I’m planning to follow Abel. This has something to do with zeitgeist, if you want to put it that way. I think that all the great moral energy which was necessary to fight the Nazis—when finally victory was achieved there was a moment of total exhaustion. And nobody any longer seriously believed in what had encouraged millions to fight the Nazis and even to die. I mean many wars have been undertaken for a certain or just cause but never more so than in the struggle against fascism and Hitler. The trouble was that also you became aware that it wasn’t stamped out, just pulverized. My feeling is that instead of having one wicked Satanic dictator or a group of wicked people—the Nuremberg defendants, many of them—who demoralized a whole nation, nowadays it’s pulverized and each of us carries within himself a little bit of that venom, instead of 18 millions Nazis, nowadays there are in this world 500 million Nazis, if not more.

BW The trials, then, were false because they suggested that evil could be juridically exorcised and the world put right again?

GvR It’s like that famous statue of the chaps planting the American flag after the Battle of Iwo Jima. The good cause was fought for and won, and now we’re going to make a law that will eliminate the possibility of having the horrors repeated forever. That was too much. Too high.

BW You say that your greatest enemy is stupidity?

GvR Not mine only. You can claim that a man is born good and not wicked, but certainly not that all men are born intelligent. There’s a question also of quantity. Put ten people together and the quota of intelligence is brought down to almost zero. And if you put one hundred thousand together, well, it’s all over then. Plant a great idea, a magnificent invention, or a great example into the mass of mankind and it becomes what Jesus Christ became—the Catholic Church. Endless chains of misinterpretations and misunderstandings—that’s what I call stupidity. A really stupid and dull person can be as amiable as anybody else—charming, but not intelligent. The accumulating and progressive stupidity of mankind is something I fear. And it can’t be fought.

BW And it’s much more pronounced in mass societies.

GvR Of course. The very moment you form a mass out of a certain number of people, it necessarily becomes a body of stupidity.

BW What values enable you to keep on, to continue writing and living with evident grace and vivacity of spirit, in spite of such profound pessimism.

GvR You see it’s the secret of the “I”. In spite of all the strange morphologies and transformations of myself during my lifetime, the “I” is something unchanged, something I can’t explain, not even to myself, and it has its destiny. I believe in that. I may be very capable of suicide, certainly, but I believe that the hour has to come for it. The hour has to come for my dying, anyway. As long as there is life, I shall try to cope with the outer world.

BW And other people?

GvR Certainly. The strange thing is that I despise the mass but I love other people. It’s paradoxical, but I really do. I feel friendly towards everybody I meet. Basically. But in the whole I despise them.

BW One last question. You’ve said, “I’m an aesthetic absolutist and an ethical nihilist.” Can you elaborate?

GvR (laughter) Ah, but what is there to add to that?

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

- Immanuel on the Green March 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

This is von Rezzori at his best:

“In a cameo set as a brooch, a melancholy faun, sitting under an olive tree, blows on his panpipe; above him are seen the three richly flowing feather panaches of the crest of the Prince of Wales, together with the device Ich dien. The brooch lies in a velvet jewelry box in the lid of which, tipped open, the warrant of arrest for Landru, mass murderer or women, has been pasted. There are ice-flowers on the windows, and some newspapers in cane frames are lying on the marble tabletop of a Viennese coffeehouse. The lady in the back, behind the cash box, wears her short-cropped hair brushed down over her brow and is clad in a wasp-waisted dress; as with “The Lady Without a Lower Half” in a circus sideshow, only her upper trunk can be seen. She holds a magnifying glass in her hand which she discreetly hides whenever someone looks at her.”

-von Rezzori SNOWS OF YESTERYEAR pg 233