About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Houses of Parliament, Cape Town

Die Parlementsgebou, Kaapstad.

The insignia of the Parliament of South Africa, showing the Mace and Black Rod crossed between the shield and crest of the traditional arms of South Africa.

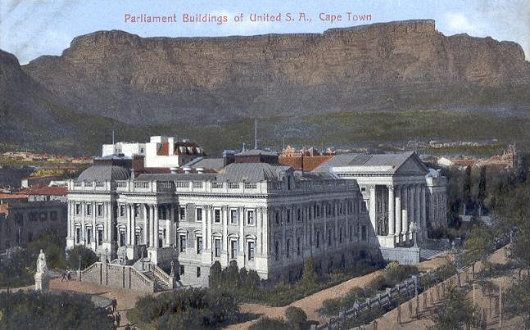

CAPE TOWN IS justifiably known as the “mother-city” of all South Africa, paying tribute to that day over three-hundred-and-fifty years ago when Jan van Riebeeck planted the tricolour of the Netherlands on the sands of the Cape of Good Hope. Numerous political transformations have taken place since that time, from the shifting tides of colonial overlords, to the united dominion of 1910, universal suffrage in 1994, and beyond. The history of self-government in South Africa has unfolded in a well-tempered, slow evolution rather than the sudden revolutions and tumults so frequent in other domains. No building has born greater witness to this long evolution than the Parliament House in Cape Town.

The British first created a legislative council for the Cape in 1835, but it was the agitation over a London proposal to transform the colony into a convict station (like Australia) that threw European Cape Town into an uproar. The proposal was defeated, but the colonists grew concerned that perhaps they were better guardians of their own affairs than the Colonial Office in far-off London. In 1853, Queen Victoria granted a parliament and constitution for the Cape of Good Hope, and the responsible government the Kaaplanders so desired was achieved.

Sir Charles Henry Darling, acting governor, ceremonially opened the first Cape Parliament in the State Room of the Tuynhuys (at the time known as Government House), the Governor’s official residence, but it soon became apparent that none of the administrative buildings in the mother-city were suitable for housing the body. The Parliament soon found a home in the stately dining hall of the Lodge de Goede Hoep, a masonic lodge of the Grand Orient of the Netherlands founded in 1772. The Lodge building itself (erected 1802) is one of the stateliest structures in the Cape, designed by that master of architecture, Louis Michel Thibault. The dining hall (above) is a slightly later construction, but by no means lacking in handsome detail. The House of Assembly found the Hall suitably capacious for its needs while the Legislative Council, the Cape Parliament’s upper house, met at the Old Supreme Court building nearby (now styled the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum), another of Thibault’s achievements.

With the expansion of the Cape Colony, the responsibilities of the parliament grew and it became apparent that the ad-hoc nature of the legislature’s accommodation. The Public Works Department commissioned the architect Charles Freeman, responsible for a number of other structures around the town. Freeman handed over plans for a domed edifice (above) with end pavilions in an overall composite classical style. Governor Sir Henry Barkly laid the cornerstone in 1875 and the bulk of the building was constructed according to Freeman’s plans. The architect, however, had poorly judged the foundations of the building and the dome had to be abandoned, an affair which caused some scandal at the time and drove Freeman from the office of government architect into private practice. Henry Greaves amended Freeman’s plans, and the building was completed — without dome — in 1884.

The result is a handsome building, nestled in the Company’s Gardens in the middle of Cape Town. I actually prefer it without the dome, which, as Dino Marcantonio has rightly pointed out, is more properly the domain of the sacred realm rather the profane. The front of the building faces on to Parliament Street, while the rear façade fronts onto Government Avenue, the tree-lined lane that acts as the spine of the Gardens. The way to tell the front from the rear is that the columns of the central portico are in four groups of two at the front, whereas they are evenly placed on the garden side.

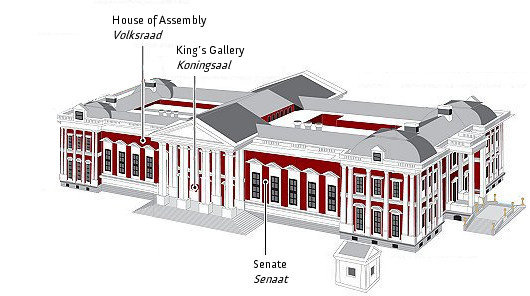

After the Anglo-Boer War, all of southern Africa was under the rule of the British crown. The National Convention was summoned in 1909 to determine how to bring together the Cape, Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State into a single country. Meeting in the Cape Assembly’s chamber, the Convention laid the foundations of the new constitution for the Union of South Africa, proclaimed a year later in 1910. One of the constitutional compromises was on the touchy issue of in which province to place the capital. It was decided to make Pretoria the executive capital, home to the national administration, Bloemfontein the judicial capital, home to the highest courts in the land, and that the legislative capital would be Cape Town, home to the parliament of the new nation. The government of the Cape Province moved to a new building, the Pronvisiale-gebou, across the street, while the new Parliament of South Africa would inherit the home of the old Cape Parliament.

Rising up the broad staircase, the visitor to the Houses of Parliament passes through the entry columns into the King’s Hall, or Koningsaal. This columned lobby links the old Senate chamber on the right with the House on the left. The lobby took its name from the royal portraits which lined the walls until the proclamation of the Republic in 1961. In that year, all the royal portraits in the Parliament House were removed to a single room to be exhibited as historical curiosities. The presence of new portraits led the King’s Hall to be renamed the Gallery Hall.

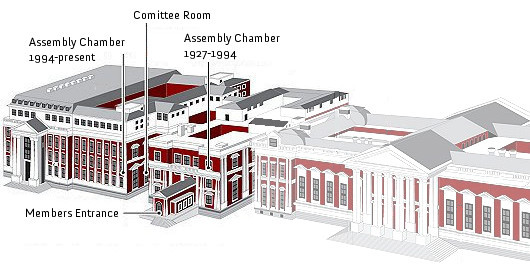

In the 1920s, Parliament commissioned Sir Herbert Baker to build an extension to the building, including a new chamber for the House of Assembly. The old Assembly chamber became the Parliamentary Dining Room, run by the catering department of South African Railways & Harbours. A further extension was created in the 1980s, when the 1910 constitution was replaced with the awkward & novel tricameral constitution which provided a parliamentary house each for Whites, Coloureds, and Indians. Further constitutional changes, as we shall see, moved the center of power away from the old building and towards the newer wing.

Cape Town — Kaapstad

Part I: The Houses of Parliament, Part II: The Senate, Part III: The House of Assembly, Part IV: The National Assembly, Part V: The State Opening of Parliament

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Andrew –

Thanks for this post. I have often wondered about the layout and design of various parliament houses around the world, including South Africa.

Harold

Greetings

The history of the Houses of Parlement is fascinating especially the events of the archi

tect Mr Freeman.

I was told that there is a small aquafere running under the Houses of Parliament.

Can you tell me if that is true? Where does it start? Where does the water flow to?

Looking forward hearing from you and thanking you in advance.

Kind regards

C Courtois

Hi topical subject at the moment . I am looking for Freeman’s original plans. I would like to do a cross post of your excellent piece to the Heritage Portal. thanks Kathy