About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

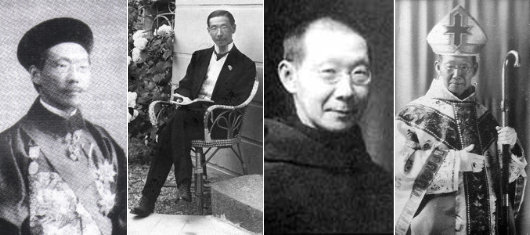

The Prime Minister of China who became a Benedictine Abbot

CHRISTIANITY HAS A LONG and varied history in China stretching over at least one-and-a-half millenia. The ancient country has even had Christian leaders, such as the Congregationalist founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen, and his Methodist successor, Gen. Chiang Kai-shek (head of the Kuomintang for nearly forty years). Still, until I read this fascinating story in the Catholic Herald I had no idea that there was a Prime Minister of China, Lou Tseng-tsiang (陸徵祥), who ended his days as a Benedictine monk by the name of Dom Pierre-Célestin. Lou was born a Protestant in Shanghai in 1871, but married a Belgian woman and eventually converted to Catholicism. Serving his country in the diplomatic arena, he accomplished extensive reforms of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, avoided becoming part of any of the various factions that divided the government, and was one of the founding members of the Chinese Society of International Law. Lou bravely stood up to the indignities imposed upon China through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by refusing to sign the shameful document which sewed the seeds of future disaster.

Xu Jingcheng, Lou’s mentor and sometime Ambassador to the Court of the Tsars in St. Petersburg, instructed the up-and-coming diplomat that “Europe’s strength is found not in her armaments, nor in her knowledge — it is found in her religion. … Observe the Christian faith. When you have grasped its heart and its strength, take them and give them to China.”

After the death of his wife, Lou became a Benedictine monk at the abbey of Sint-Andries in Flanders, and was eventually ordained a priest in 1935. A decade later, Pope Pius XII — who cared deeply for the Church in China and finally settled the long-standing dispute over Chinese ancestor-honouring rituals in favour of the practices — appointed him titular abbot of the Abbey of St. Peter in Ghent. Sadly, the Chinese Civil War prevented Dom Pierre-Célestin from returning to China, and he died in Flanders in 1949.

The words of Lou’s mentor that Europe’s strength is her faith found recent confirmation from Professor Zhao Xiao, a prominent Chinese economist at the University of Science & Technology Beijing. Prof. Zhao, a member of the Chinese Communist Party, began studying the differences between the economies of Christian societies and those of non-Christian societies. As a result of his investigations, he argued that Christianity would provide a “common moral foundation” for China that would help the economy by reducing corruption, narrowing the gap between rich and poor, preventing pollution, and promoting philanthropy.

“A good business ethic or business morality,” Prof. Zhao says, “can provide for a type of motivation that transcends profit seeking. Why do people want to do business? The main goal would be to earn money. The purpose of a company is to maximize profits. But this can cause companies to look for quick results and nearsighted benefits. It can cause companies to disregard the means and earn money at the expense of destroying the environment, society and the livelihood of others, or endangering the entire competitive environment of the trade.”

“If my motivation for doing business is the glory of God, there is a motivation that transcends profits. I cannot go and use evil methods. If I used some evil methods to enlarge the company, to earn money, then this is not bringing glory to God. Therefore, this is to say that it [bringing glory to God] can provide a transcendent motivation for business. And this kind of transcendental motivation not only benefits an entrepreneur by making his business conduct proper but it can also benefit the entrepreneur’s continued innovation.”

This transcendental aspect of Christianity, which is so obviously fading in the economic aspect of what we no longer have the confidence to call Christian countries is, according to Zhao, essential to the societal advantageousness of Christianity.

“There is no culture that can match Christianity’s degree of prizing love, because what it emphasizes is a form of unconditional love, a love for everyone, including those who are not lovable, including those who have hurt you or oppressed you. You have to love them, regardless of whether they are good or bad to you, regardless of whoever they are, you must love them. So this kind of love is a sign of the openness of modern society and modern civilization.”

While Prof. Zhao’s arguments in favour of Christianity as good for China are utilitarian in origin, the professor eventually converted to (Protestant) Christianity himself, while retaining his membership in and support of the Communist Party.

The Chinese Communist Party, Zhao argues, “is no longer a political party that is filled with revolutionary characteristics but rather one that has transformed into a ruling political party with widespread representation. … We see that the Communist parties of the Soviet Union and all of Eastern Europe have collapsed, and their countries have collapsed with them. But the Chinese Communist Party survives precisely because it continues to change. …”

“I talk about how China’s transformation must have a moral foundation. This, it has to be said, is a widespread consensus. At the same time, I proposed that the formation of this kind of morality could be in the spirit of a mix between the traditional culture of China and Christian beliefs, a process of blending. I had thought that many people would oppose me, including recently at discussion at a club in Qinghua University attended by many Chinese elites. But what made me feel strange is that they all supported me. There are aspects of my argument that they disagree with. For instance, my using America as an example, they don’t agree. They say, ‘Look, there are some areas where America did not do a good job.’ They did not agree with my evidence, but they agreed with my overall viewpoint.”

As Zhao Xiao told an interviewer from PBS, “I discovered that there is a foundation of morality behind the American market economy”. Sadly, that foundation appears to be rapidly diminishing here in the West. Bernard Madoff, admittedly, was no Christian, but the Christian principles which once restrained and encouraged our businessmen and consumers, and which were held as a standard for all of society, have been ditched in the name of “progress”. And of course, with our perpetual warfare, bottomless pit of debt, and never-ending inflation, we can see what good this “progress” has done us. It is fascinating that, just as we abandon our inheritance, there are others outside the West who are preparing to keep it going. God willing, there will be a day when both China and the West can enjoy the full blessings of a Christ-oriented society which we both currently lack.

Our Lady of China,

pray for us.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories