About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

No. 6, Burlington Gardens

Sir James Pennethorne’s University of London

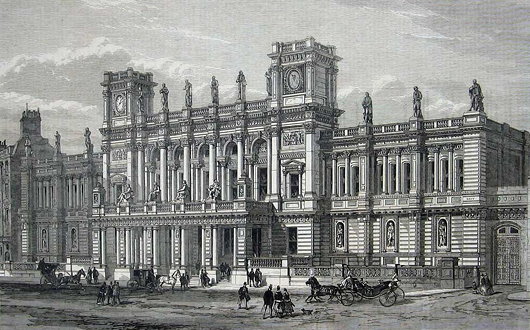

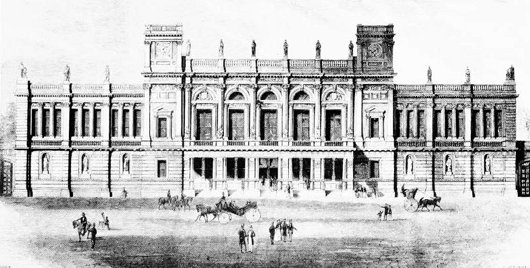

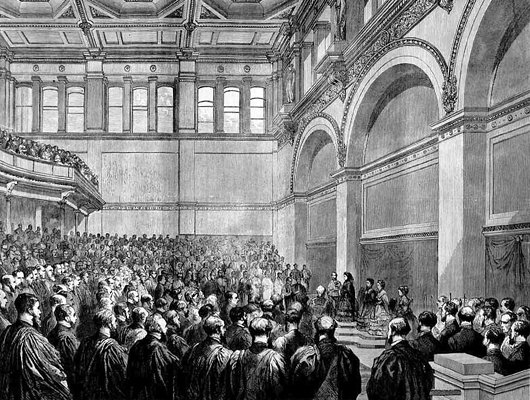

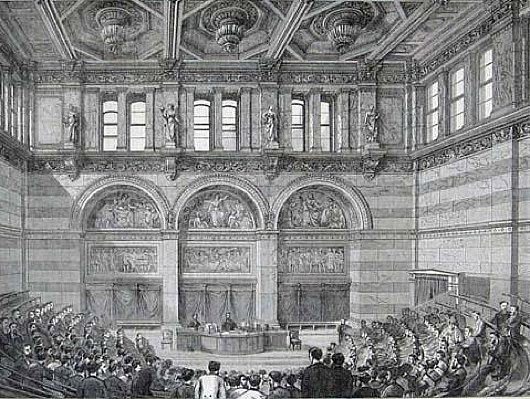

German university buildings are an (admittedly unusual) obsession of mine, and I’ve often thought that No. 6 Burlington Gardens is London’s closest answer to your typical nineteenth-century Teutonic academy’s Hauptgebäude. And the connection is appropriate enough, as No. 6 was built in 1867-1870 for the University of London in what had once been the back garden of Burlington House (which at the same time became home to the Royal Academy of Arts). Despite the building’s Germanic form, the architect Sir James Pennethorne decorated the structure in Italianate detail, providing the University with a lecture theatre, examination halls, and a head office. Pennethorne died just a year after drafting this design, and his fellow architects described it as his “most complete and most successful design”.

The University of London was founded as a federal entity in 1836 to grant degrees to the students of the secularist, free-thinking University College and its rival, the Anglican royalist King’s College. It now is composed of eighteen colleges, ten institutes, and a number of other ‘central bodies’, with over 135,000 students.

Since its founding, the University had been dependent upon the government’s purse for funding, as well as for housing. Accomodation was provided in Somerset House, then Marlborough House, before evacuating to temporary quarters in Burlington House and elsewhere. It was not until the 1860s that Parliament approved the appropriate grant for a purpose-built home for the University to be erected in the rear garden of Burlington House.

The relative simplicity of the design was contrasted by a healthy dose of sculptural accompaniment. Statues of Newton, Bentham, Milton, and Harvey adorn the portico, representing (respectively) Science, Law, Arts, and Medicine, while the Galen, Cicero, Aristotle, Plato, Archimedes, and Justinian stand atop the main balustrade. The east wing of the façade houses statues of ‘illustrious foreigners’: Galileo, Goethe, and Laplace atop the balustrade with Leibnitz, Cuvier, and Linnaeus in the niches. The ‘English worthies’ grace the west wing: William Hunter, David Hume, and Sir Humphry Davy on the balustrade and Adam Smith, Locke, and Bacon in the niches. Hume replaced the original choice of Shakespeare, with Davy replacing John Dalton. It was decided that, as “the genius of Shakespeare was independent of academic influence”, he would be honoured with a sculptural monument inside the building.

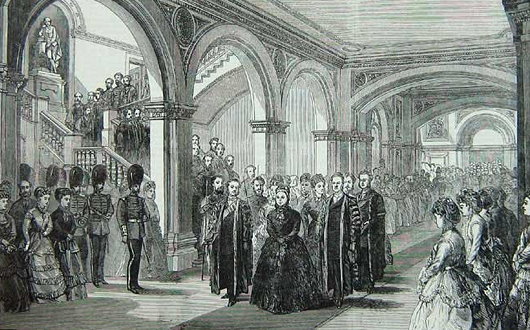

Queen Victoria ceremonially opened the building upon its completion in 1870 — “in pouring rain”, the Survey of London tells us.

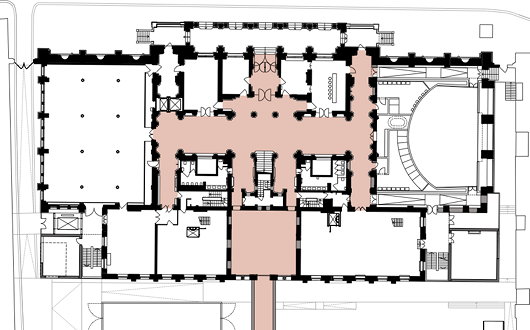

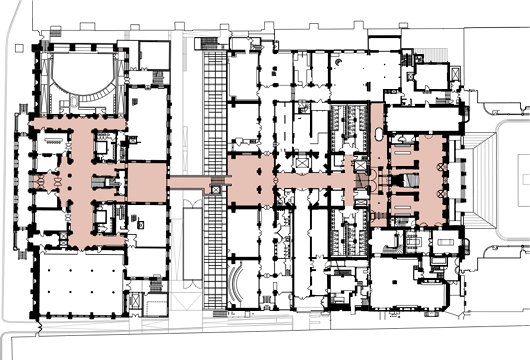

The University decided to move out to the Imperial Institute in South Kensington in 1899, and No. 6 was temporarily home to the British National Antarctic Expedition before being allocated to the Civil Service Commission in 1902, which partly shared the building with the British Academy. The Commission significantly rearranged the structure of the building, dividing the triple-height lecture theatre into three new floors of offices and making other utilitarian alterations. It left in the 1960s, and in 1970 the Ethnology Department of the British Museum opened its collections for viewing as the Museum of Mankind. The M.o.M. remained here until 1997, when the departure of the British Library for its new building freed up space at the British Museum in Bloomsbury. The neighbouring Royal Academy then wisely purchased the vacated building, commissioning Michael Hopkins & Partners to integrate it with Burlington House, but the Heritage Lottery Fund was not persuaded by the high cost of the conversion.

In 2008, the Royal Academy held a competition to design a new integration of the two buildings, which was won by David Chipperfield. In order to fund the transformation, the RA have leased No. 6 out to two galleries: Haunch of Venison from 2009 to 2011, and now the Pace Gallery. The Royal Academy hopes Chipperfield’s scheme will be implemented by the RA’s two-hundredth anniversary in 2018.

“The project will effectively double the area of public space available in the RA,” Building Design reports. “The upper-level galleries alone are two and a half times the size of the Sackler galleries. The question of how all this space will be programmed in the long term remains the subject of much debate within the RA and is no doubt being monitored closely by other institutions such as the ICA and Somerset House, for whom the emergence of such a venue may represent a considerable challenge. However, after more than a decade of frustrations, it now looks increasingly certain that 6 Burlington Gardens is set to form an integral part of the Royal Academy.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Am I the very first person to point out to you, Mr Cusack, that ALL of your obsessions are unusual?

Somehow I doubt it.

Obsessions are by definition unusual. Otherwise, they are called hobbies.

The detail in this post leads me to but only one conclusion: less time time in the library and more time at the keyboard will make the rest of us happier.

What a beautiful building. I love the decorative aspects of it, sculpture, columns, etc.

Chipperfield’s hand, at once both brutal and surgical, is the very worst one to deal with this building: has anyone seen his ‘intervetion’ at the Neues Museum, Berlin?