About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Palace on Princes Street

The North British & Mercantile Insurance Company, No. 64 Princes Street

PRINCES STREET IS the thoroughfare of the nation, and its sad decline during the second half of the twentieth century and only partial comeback since then are reflective of Scotland itself. The architects of Edinburgh’s New Town had no idea that Princes Street would evolve into a commercial avenue, and the street was originally laid out as a handsome row of Georgian townhouses, built between 1765 and 1800, facing Princes Street Gardens and the Old Town above behind them.

Almost immediately the mercantile and social nature of the street began to assert itself, with shops and traders setting themselves up in the converted basements and ground floors of townhouses. The New Club showed up at No. 86 Princes Street in 1837, coming from previous premises in St. Andrew’s Square and before that Shakespeare Square (where the former G.P.O. now stands).

As the Victorian era progressed, more and more of the Georgian townhouses were demolished and replaced with new buildings in the varying styles of age. It was just two years after Victoria’s death that an old company built a new headquarters in a brimming Edwardian baroque: the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company.

The North British was founded in 1809, merged with the Mercantile Fire Insurance Company in 1862, and by 1901 had acquired sufficient subsidiaries that its remit had extended to marine risks and general insurance. Given this expansion, a new headquarters on the principal thoroughfare of the nation’s capital seemed an appropriate expression of confidence and the NB&M commissioned Sir George Washington Browne for the task. Browne was born in Glasgow in 1853 and was first apprenticed to an architects’ firm there at 16. After some work in London he won the Pugin Studentship, allowing him to travel to France and Belgium, where he inculcated himself in the French Renaissance style.

Two years later he came to Edinburgh and worked as an assistant architect to Robert Rowland Anderson, who devised such city landmarks as the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and Edinburgh University’s McEwan Hall. Within two years he was made a partner at the firm, and not long after that Browne launched his own firm, which won the contract for Edinburgh’s Central Library in 1887 and the Caledonian Hotel at Princes Street Station in 1899, the latter commission after his firm merged with his new partner John More Dick Peddie.

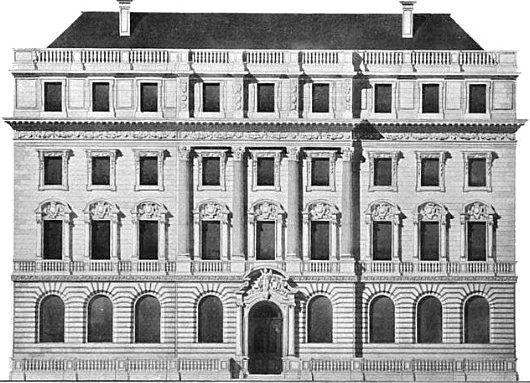

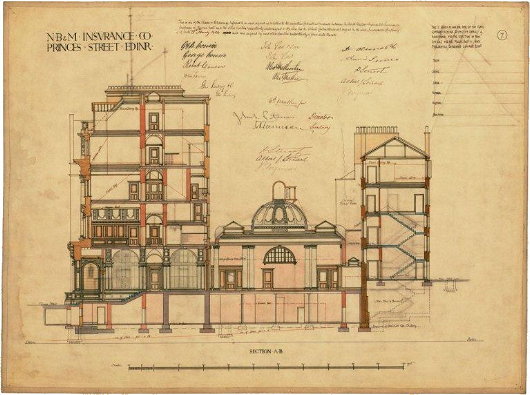

Browne & Peddie gave the North British & Mercantile a splendid classical palazzo spread over four principal stories on a large scale. The rustication of the ground floor gives way to a first story with window surrounds of particular elaboration. The second floor is more simplified and is followed by a decorative cornice completed by the final storey, crowned with a balustrade.

The Apostle Andrew, Scotland’s patron saint, stood guard over the building’s entrance.

Visitors entering No. 64 Princes Street were greeted by a grand stairway to the left which ascended to the board room and principal offices on the floor above. The ground floor included a larger hall for general inquiries from customers and policy-holders.

The interior furnishing of the offices was in a dignified classical style, mostly restrained but with occasional flourishes toward the more elaborate and fancy, if not quite fanciful. It is difficult to imagine a large insurance company building offices as handsome as this, but it was par for the course at a time when tastes were better and standards higher.

In 1959, North British & Mercantile became a subsidiary of the Commercial Union Assurance Company. (Commercial Union merged with General Accident to form CGU in 1998, which merged with Norwich Union in 2000 to form Aviva). In 1964 the company put its magnificent palace on Princes Street up for sale.

The ‘Princes Street Panel’ first convened in 1954 and in the 1960s made a number of highly controversial recommendations. The Panel wanted the entirety of Princes Street to be demolished and replaced by Brutalist monstrosities, with a pedestrian walkway above the ground floor theoretically doubling the pedestrian-accessible retail space on the street. The department store chain British Home Stores bought the old North British & Mercantile headquarters as well as the building next to it, demolished them both, and decided to build the first Brutalist structure according to the Princes Street Panel’s recommendation.

The result, I think, speaks for itself. Despite a popular outcry, the assualt on Princes Street didn’t end with BHS. The New Club, the most prominent private club in the city, was even convinced to tear down its classical pile and replace it with a Brutalist monster. (The silver lining is the Club’s decision to salvage some interior panelling and re-apply it in the new building).

Princes Street wasn’t perfect before the Brutes had a go at it, but there can be no doubt (except in the minds of those sufficiently indoctrinated into the cult of modern architecture) that they and their confreres made it worse. One particular problem is that where there is good architecture, it rarely reaches down to the ground floor. The building to the left of BHS, for example, is a fine structure, but at street level there is nothing but a bland, cruel box with sharp edges that bears no relation to the structure above. A canny landlord would replace the box with a more sympathetic brick facing, perhaps in a style suited to the rest of the building. This would still allows for the great amount of window space required by modern shops, while at the same time creating a more harmonious appearance that would be more inviting to shopgoers.

The street is currently being turned over by the laying of tracks for Edinburgh’s new tram system. I hope they will take this opportunity to reduce traffic lanes and increase space for pedestrians, especially on the narrow, perpetually overcrowded Gardens side of the street.

The newer architecture on the street, while generally inoffensive, is still nothing worth writing home about. It is tempting to hope the Brutalist monsters stay for today, knowing that the property developers would only build mediocre replacements for them. But Scotland herself has Robert Adam at the ready, and there are even more traditional architects south of the Tweed. Good architecture is possible now, it just isn’t getting the best commissions.

Edinboronians and visitors to the capital would infinitely prefer the old palace of the North British & Mercantile to the Brutalism of the British Home Stores. Replacing the latter with new architecture in tune with the former will be a major step in reinvigorating Princes Street.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

It should be reconstructed, down to the last detail.

I screamed when I saw the replacement. I had been saying in my head “please don’t have been torn down, please don’t have been torn down”.

Agreed, gentlemen.

I had never seen images of the interior before. Now there is a stone in my gut.

The one thing that makes the heart glad, though, is having seen the mercifully unexecuted designs for Princes Street and the Old Town that were produced in the 60s by the city architect (who can also be glad to have remained mercifully unexecuted).

The construction of that monstrosity didn’t only mean the destruction of such jewell; it also makes it impossible to appreciate the surviving beauty on Princes St. That abomination sucks everything around it into its aberrant ugliness like a black hole.

60’s Labour councils have a lot to answer for.

How sad to that building demolished. The woodwork in the offices is very similar to some of the second floor offices at the Frick Collection. Museum quality, and they tore it down?! Well I guess the 1960s and 70s were really an era of bad taste and stupidity. Think of how much the British Home Store could have profited now if it still could boast it’s “palatial decor”.

I’m only glad that the photographs and plans survive. Such a loss! I have to agree the street is blighted by BHS and its contemporaries. Unfortunately architectural fashion has moved against traditional design recently (see the new building on the corner of George IV Bridge and the High Street) so it could be a long time before you see a replica!

I am sick to death of the publically endorsed and financed vadalism that has been done to our city. There are so many examples stretching back over the last 50yrs. It’s high time that some of these buildings were restored and legislation passed to facilitate the cessation of this destruction of our beautiful heritage. Perth Council are just about to demolish the fabulous City Hall (http://www.thecourier.co.uk/News/Perthshire/article/16102/dundee-institute-of-architects-registers-its-opposition-to-wanton-destruction-of-perth-city-hall.html)

“But Scotland herself has Robert Adam at the ready, and there are even more traditional architects south of the Tweed. Good architecture is possible now, it just isn’t getting the best commissions.”

Is the writer seriously proposing mock Victoriana as contemporary “style”? We all know the 60s enthusiasm for Internationalist Modernism ruined many inner cities but it was out of positive view for the future of Architecture and urban living. I pray we continue to look to the future.

I can feel tears pricking my eyes looking at the before and after photos – I get the same reaction when I look at what replaced Sir James Gowan’s Rockville.

Very interesting article and so glad the original photos of that beautiful building can still be seen. I worked in the building as a shorthand typist from 1957 to 1962 and later, when returning to Edinburgh, and found the building demolished, I felt such rage. It was complete vandalism.