About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Preservation is Not Enough

A Proposal for Enhancement

IT IS COMMONLY said of St Andrews that it is a place of beauty. This is often a compliment to its natural setting, with open skies arcing over the reaches of the bay, and ancient rock and cliff yielding to the changing rhythms of the waves. At the same time visitors are generally struck by the pleasing combination of natural and built environments: the ruined grandeur of the Cathedral and Priory standing bare to the elements; crowstep-gabled cottages gathered in against the wind; the broad thoroughfares interlinked with narrow cobbled lanes; and the church towers etched against the sky. There is also the scholarly dignity of Deans Court, the quizzical posture of the Roundel, the charm of the courtyards to the south of South Street, the sad ruination of Blackfriars juxtaposed with the aspiring frontage of Madras College, and other evocative sights besides.

Here and there within the midst of all of this stands, physically, historically, and socially, the University. Its contributions to the architectural distinction of the old town are obvious enough. They are, principally, the harmonious South Street complex of St Mary’s College (1593-41) to the west, Parliament Hall (1612-43) to the north, and the Library extension (1889-1959) – now the Psychology wing – to the east; and the North Street set of the Collegiate Church of St Salvator, Gate Tower and tenement (1450-60), and beyond it the west block (1683-90) containing the Hebdomadar’s Room, and to the east and north the College buildings (1829-31 and 1845-6, respectively). There are other smaller and oft-reworked jewels associated within the University: St John’s House in South Street (15th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries), St Leonard’s Chapel (remodelled c. 1512), and the ‘Admirable Crichton’s House’ (16th century), but the principal architectural benefactions of the University to the town are the North and South Street college complexes. I have not mentioned the Younger Graduation Hall (1923-9) and the Student Union (1972) and prefer to leave it for readers to determine what might be said of these.

It could hardly have passed unnoticed that the list of contributions dates mostly from the late middle-ages to the nineteenth century, and this fact raises two questions: first, whether in the second half of the twentieth century the University was sufficiently attentive to its role as principal architectural patron; and second, how it might now hope to enhance the built environment of St Andrews. The main in-town developments since 1950 are the Buchanan Building (1964) and the University Library (1972-6) both of which are essentially functional solutions to practical needs rather than exercises in collegiate architecture. It is worth saying that given the conditions obtaining at the times of their creation both could have been much worse in design and building quality. As it is, the first has the merit of being more or less unnoticeable from the street, while the second has the virtue of truth-to-function, looking to be what it is, namely, several stories of book cases.

The simple fact is that the expansion of the University was (and continues to be) achieved without any great endowment or enhancement in its funds. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in modern times it has been unable to give thought to the aesthetic improvement of the town. But this state of affairs cannot long continue without the charge of philistinism beginning to arise. The University is audibly proud of the distinction of its teaching and research, of its place in various national and international rankings, and of its appeal to well-qualified students from around the world. But the first and last are mortal resources, and approval of is no substitute for determining to do what is right on its own account.

The time is (over)due for the University to address the matter of its material contribution to the environment of the town of St Andrews. It should aim to devise one or more projects whose products will outlast the generations of those managing, teaching, and studying in the University now, and among these projects should be an enhancement of the built environment. The scope for extensive building is limited by the want of plots, funds, and needs. In town there are large sites to the north of the library and to the west of Castlecliffe (1869) but the cost of developing these would be very great and would only be justified by major projects for which there is currently no general call. (The exception is the need of a University art gallery and museum but, important though this is, I set it aside for now).

It would be easy to use the excuse of a lack of means and demand as grounds for postponing the day when the University will set about making a significant architectural contribution, but that overlooks other possibilities. In particular there is the matter of enhancement of existing sites. Landscaping offers one means of pursuing this, and although the University has made some progress on this front it has been too willing to limit itself to the maintenance of existing plantings rather than creating new schemes. But in any case landscaping is at best a complement to building in stone and not a substitute for it.

It is necessary to take account of the funding difficulties affecting St Andrews along with other British universities (and anticipating the possibility that this will worsen for Scottish institutions as a result of different funding and income patterns north and south of the border), but also to remember that St Andrews already has some significant architectural settings, and that its current students and friends are probably better placed than their counterparts in past decades to contribute to projects that are both inspiring and realistic. With these points in mind I would like to propose that a scheme be taken up and pursued by the time of the sexcentennial celebration of its formal establishment in 1413/4. (The 1412 charter of Bishop Wardlaw was confirmed by a series of Papal Bulls issued by Benedict XIII in 1413 and promulgated by him in February 1414).

Where then to focus such an effort? The oldest University buildings are the original St Salvator’s set. It is generally agreed that the most impressive element of these is Bishop Kennedy’s Tower. Rising up above the main entrance to the College it faces in four directions three of which are to the world beyond and one is inward to the place of learning. Its plainness (some might say “austerity”) is offset by the bays of the chapel seen on the North Street side and by the cloister and view across to the College buildings as one enters through the gateway. Here, though, there is a problem.

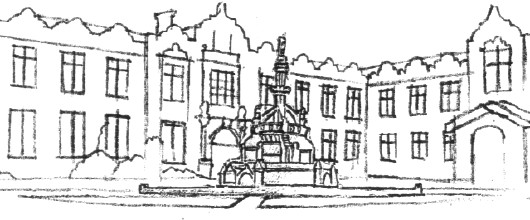

In 1827 visiting Royal Commissioners judged that the Common Hall and School of Bishop Kennedy’s original 15th century design were “entirely ruinous and incapable of repair”. Their dilapidation meant that nothing could be done other than demolish them and build anew. In 1828 a set of plans by Robert Reid, King’s Architect for Scotland, was approved by the Commissioners and the following year building began on the east wing and was completed two years later. What we see today is in fact something of an assemblage of different ideas more or less linked by a somewhat Jacobean look. Reid’s north section of the east wing was extended in the twentieth century (1904-6) while the north range (1845-6) is by William Nixon who also added the arched cloister (1848) to the College side of the church. Nixon saw himself working within a design established by his predecessor, but while the result is not a failure nor yet is it a great success. The most obvious weakness is the point in the northeast corner of the quad where the two ranges converge, for although the blocks are architecturally related they are not fully integrated and as a result the meeting of the two is visually unresolved. The passage of the two wings north and east is simply arrested rather than merged into a new upward movement; where one might have expected a low tower or other prominent vertical feature there is simply a meeting of roof lines.

The area of the quad is large, but because of the scale and form of the chapel, tower, and hebdomadar block, the prospect from the north combine openness with visual interest. The first view the visitor is likely to face, however, is of the north and east as seen from the area adjacent to the former porters’ lodge entered from beneath the tower. Certainly the College halls are impressive but to left and right there is an absence of prominent or skyline features. The view through to lower college lawn and University House is eye-catching but architecturally low-key, while to the right there is the unresolved northeastern corner.

One architectural ‘improvement’ would be the erection of a tower at the junction of the two blocks but this is fraught with all sorts of difficulties. Another innovation, which I believe would be much preferable, would be the creation of a tall fountain in the middle of the lawn. This could be approached by diagonal pathways leading from the four corners of the quad. These could be cobble edged (as indeed should be the existing driveway). Such pathways would very aptly introduce the saltire into the ground plan and add visual interest by increasing the movement to and fro within the quad. More importantly, a fountain would provide a point of considerable architectural and symbolic importance in the heart of the university. The flow of water would also bring animation to an otherwise featureless expanse and serve as a designed counterpart to the natural movement of the sea beyond.

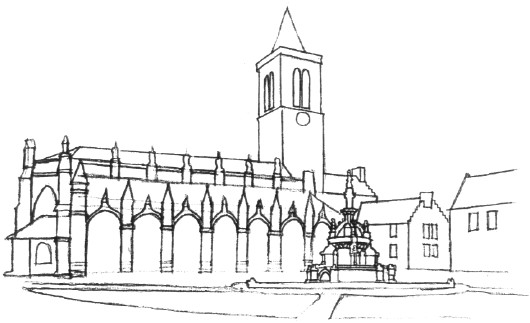

The question of what sort of design would be most apt is a large one. St Salvator’s Chapel is in the late Scottish Gothic with some Victorian additions. The College buildings owe something to the Jacobean and to the classical. In this context it would be necessary to work again within a recognisable historical tradition perhaps adding a further mediating style, With that in mind I offer a view of a possible design intended more to give the impression of how a fountain might improve the quad rather than as a specific recommendation. These show a three-tier crown fountain based on the French Gothic design of the Stewart Memorial Fountain (1872) in Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow.

With a new millennium having begun, and the six century celebration in prospect, the installation of a fountain would be a particularly timely project and one for which external funds might be especially forthcoming. Such an initiative might also serve as an encouragement to the civic authorities to restore to working order the George Whyte-Melville memorial fountain in Market Street – and perhaps even to recreate the old Mercat Cross which stood nearby from the middle ages until its removal in 1768. Then future generations of University staff, students, townsfolk, and visitors might have further reason to look with appreciation around St Andrews at what the past has bequeathed to them. How better to celebrate six hundred years of the University than to create something of beauty that might survive for as many centuries again?

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Burns Tower April 19, 2024

- Patrick in Parliament March 18, 2024

- Articles of Note: 13 March 2024 March 13, 2024

- Cambridge March 9, 2024

- Taken on Trust March 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Another possible inspiration for the fountain, rather than Kelvingrove, would be the highly ornate 16th century fountain at Linlithgow Palace.

So this age’s great contribution to the town of St. Andrews will be… a water feature?

A theoretical water feature — so far as I know, there are no plans to actually build it.

This would actually spoil the Quad and would be simply a piece of pastiche with little architectural merit. Take a look at the elegant revamped Quad of Old College in Edinburgh. No need for nasty pseudo-period fountains.

The University has actually contributed many buildings to the townscape in since 1900, mostly on the North Haugh and some have even won architectural prizes.